Every year more than 12 million people visit the White River National Forest in central Colorado to ski, hike, bike, fish, camp and otherwise enjoy this iconic 2.3-million-acre landscape. As part of the public lands system, the forest is collectively owned by the American people and managed by the federal government on our behalf. Recently Senate Republicans tried to make half of it eligible for sale.

The move came last June, when Senator Mike Lee of Utah proposed adding a provision into President Donald Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” to auction off millions of acres of public lands across the Western states. Nominally intended to provide housing and fiscal debt relief to Americans, it was the largest proposed sell-off of federal lands to date. Ultimately the provision was stripped prior to the bill’s passage into law. But this won’t be the last attempt to dismantle public lands and hand them over to private companies. In September 2025 the Center for American Progress published an analysis showing that the Trump administration had already begun taking actions that could collectively eliminate or weaken protections from more than 175 million acres of U.S. lands. With such mass-scale privatization measures ramping up, it’s worth examining what these places actually provide to people versus corporations.

As an environmental scientist who studies the complex interplay between humans and nature, I decided to analyze the costs and benefits of public land sell-offs, focusing on this failed provision as an example. I used established methods of data analysis in my field to assess publicly available datasets previously published in peer-reviewed journals and synthesize these data to illuminate the broader implications of recent policy proposals and political movements. The findings make clear that these lands are ill-suited to development for affordable housing. What is more, putting these lands in private hands means losing the host of crucial ecological benefits—from sustaining the pollinators that underpin our food supply to purifying the air we breathe—that intact ecosystems provide at no direct cost or effort to us.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Conflicts over public lands in the U.S. have deep roots. In the 1970s ranchers, extractive-industry groups, county officials and allied Western politicians, later endorsed by President Ronald Reagan, staged the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion to wrest control of hundreds of millions of acres from the federal government. In 2016 the GOP platform openly called for transferring federal lands to states and facilitating the extraction of timber, minerals, coal, oil, and other natural resources from these lands.

The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 blueprint goes further in the effort to control public lands and exploit their natural resources. It lays out a plan to roll back the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s so-called 30 × 30 initiative to protect and manage 30 percent of the world’s land, fresh waters and oceans by 2030 (Trump has already rescinded the U.S.’s 30 X 30 commitments by executive order). It calls for gutting the Land and Water Conservation Fund, a federal program that has funded the acquisition of land and interest in land to safeguard natural areas, water resources and cultural heritage and to provide recreation opportunities since 1965. Project 2025 also aims to weaken the Antiquities Act of 1906, which allows presidents to protect federal lands of scientific, historic or cultural significance by designating them as national monuments. To that end, the Department of Justice recently ruled the president has the authority to revoke national monuments, and the Department of the Interior has begun broad reviews of monuments with an eye toward development of extractive industry.

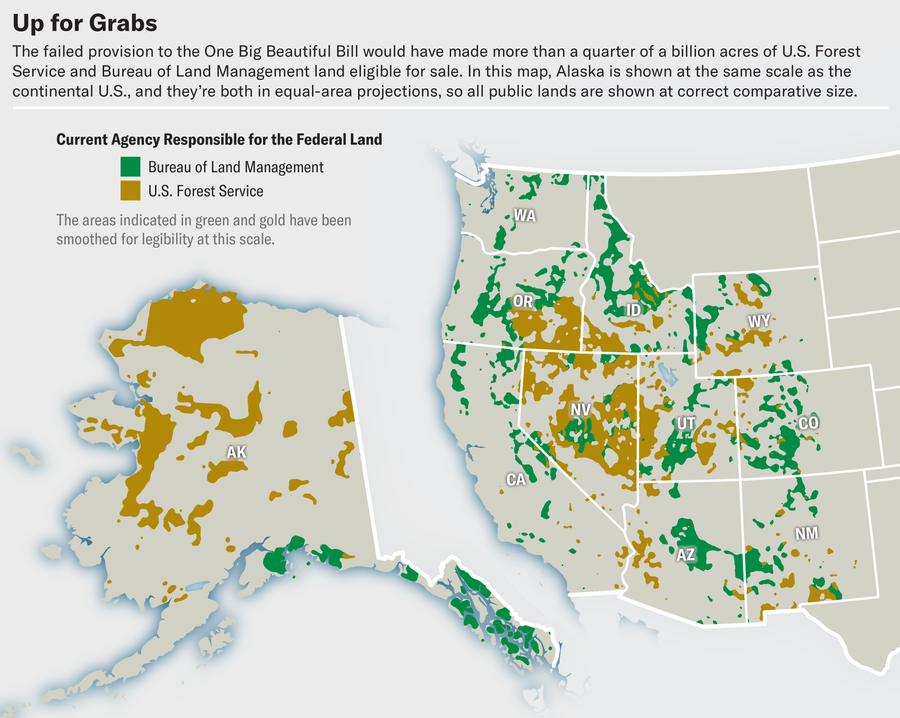

Daniel P. Huffman; Source: Data retrieved in December 2025 from Outdoor Alliance; Senate Reconciliation—National Public Lands Available for Sale

The now defunct public lands sell-off provision in the Trump administration’s bill, also known as the budget reconciliation bill, would have made more than a quarter of a billion acres of U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land in 11 Western states eligible for sale and required selling off two million to three million of those acres within five years. The provision mandated that any land sold be developed for housing and related infrastructure, a restriction that would expire after 10 years.

Proponents framed the sale as a solution to America’s housing-affordability crisis, although the provision contained no affordability requirements, nor did it stipulate who could buy the land. Could sales of federal lands actually solve the problem of affordable housing? And what are the ecological trade-offs of converting millions of acres of public land to development? There’s a lot to unpack about sell-offs. Let’s look at the data.

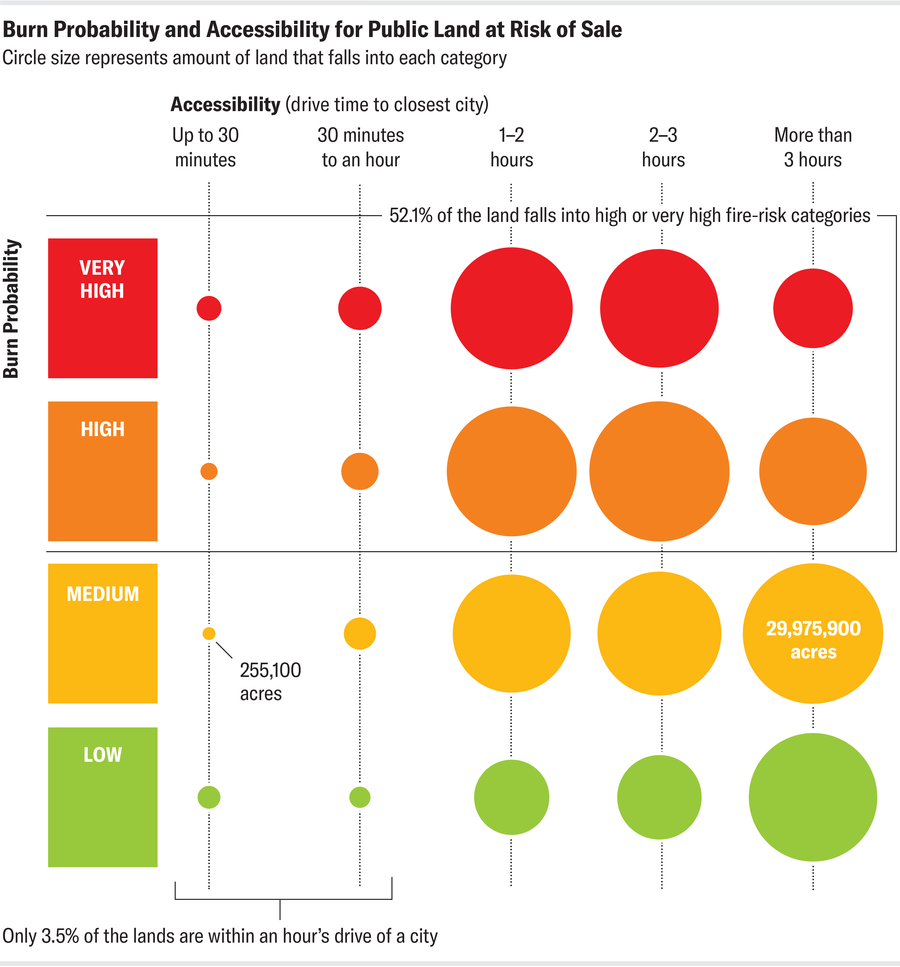

To test the claim that the Trump proposal would address the housing crisis, I evaluated whether these lands are even suitable for development in the first place, focusing on accessibility and wildfire risk. I looked specifically at the area of overlap between accessibility and burn probability, using previously published datasets on accessibility, which calculate travel time based on proximity to urban centers and infrastructure, and on fire risk within the lands eligible for sale.

I expected these landscapes to be remote and wildfire-prone, but the degree of inaccessibility and wildfire risk is staggering. Even if a developer were able to get an insurer to underwrite such a project, these homes would remain out of reach for the working-class families most in need of affordable housing because most public lands are not located anywhere near the infrastructure one needs to build homes affordably or the job centers where most Americans work.

Just 3.5 percent of these lands are within an hour’s drive of a city. Only 0.7 percent are within a 30-minute drive; 30.5 percent lie one to three hours away; 33.4 percent are three to six hours distant; and 32.6 percent sit more than six hours from urban centers. As for fire risk, 18 percent of the targeted acres lie in low-burn-probability zones, almost all in Alaska. More than 52 percent fall into high or very high fire-risk categories.

A decent chunk of this land does sit in low-burn-probability zones—could it be a viable option for housing? No. Only 0.3 percent of the acreage proposed for sale combines low fire risk with a commute under 30 minutes, and 81 percent of that tiny fraction lies in Alaska, which has no shortage of land for development. Of the 18 percent of targeted acres classified as low risk, 55 percent are more than six hours from the nearest city; 24 percent sit three to six hours out; 19 percent lie one to three hours away.

Kyle Manley and Jen Christiansen

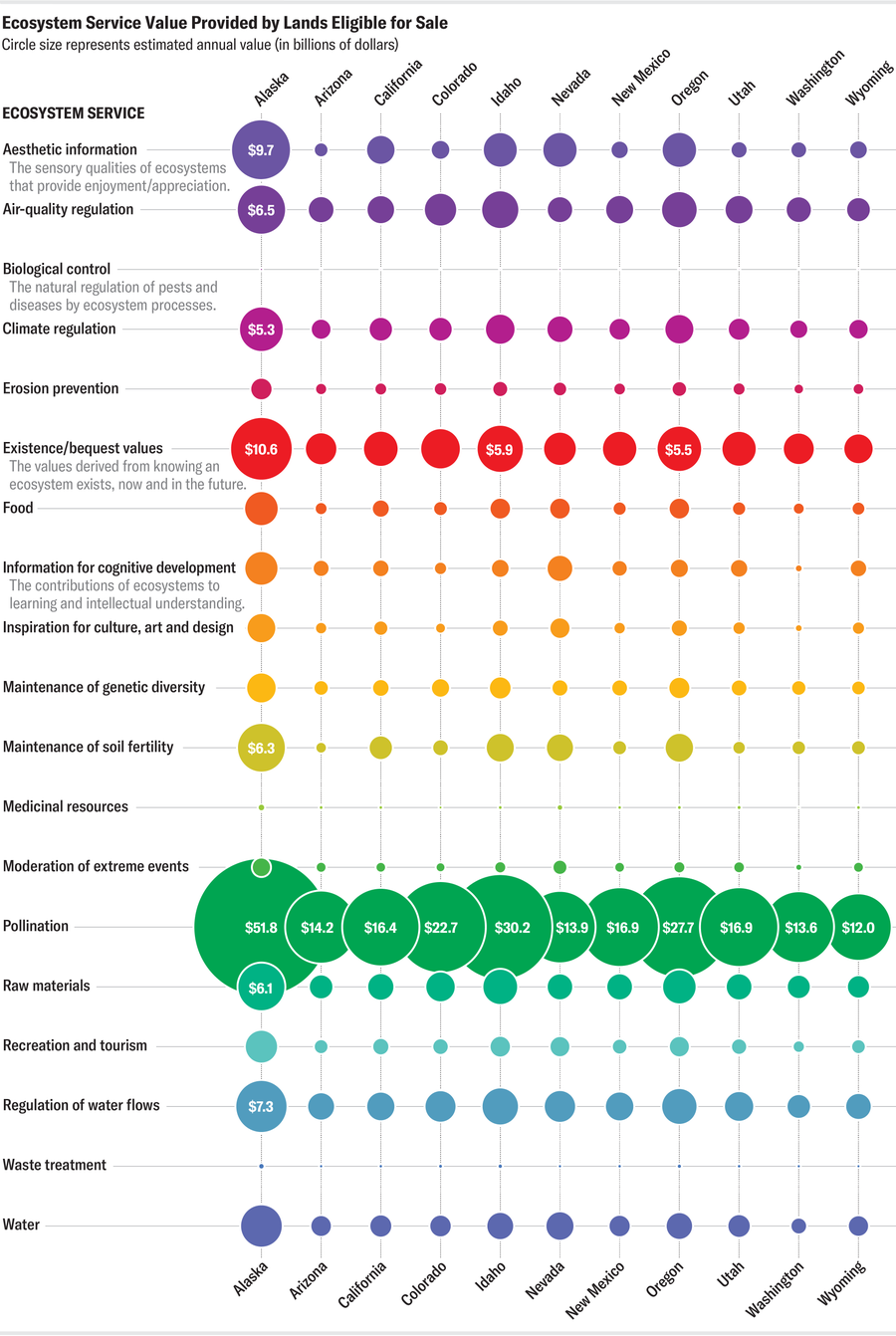

Next I set out to calculate the ecological cost of privatization. To do that, we need to understand what ecosystems exist within the public lands that were eligible for sale and look at the benefits they provide to people, also known as ecosystem services. A land-cover analysis using the National Land Cover Database reveals that approximately 137 million acres, or 53.8 percent, are shrubland/scrubland; roughly 65 million acres, or 25.3 percent, are evergreen forest; and about 27 million acres, or 10.5 percent, are grassland and herbaceous communities. These three ecosystems account for nearly 90 percent of the lands eligible for sale.

Drawing from ecosystem service values calculated from more than 1,500 valuation studies of biomes from around the world, I estimated the annual worth of services delivered by forest, shrub/scrub, and grass/herbaceous areas slated for sale and development. Altogether the ecosystems on these lands generate roughly $507.4 billion in benefits to the public every year.

Pollination alone accounts for $236.2 billion of that total. This service undergirds our agriculture and wild ecosystems. About 35 percent of global crop production, and 87 of the 115 major crops, depends on pollinators. Nearly 90 percent of wild flowering plants rely on them, too. Public lands in the Western U.S., home to immense pollinator diversity, deliver enormous value on this front.

Pollination is relatively simple to conceptualize as a benefit because it provides us with food, which is traded on our markets. But ecosystems provide much more than market values. One example is existence and bequest value, which is the value people derive from simply knowing that an ecosystem exists, now and for future generations. The public lands that were slated for sale generate $46.5 billion in this category.

Part of the existence/bequest value is related to another service: the maintenance of genetic diversity. Put simply, ecosystems support biodiversity. An analysis of species-richness data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature shows that lands eligible for sale in the Big Beautiful Bill provision support on average 261 species of amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles per 7,500 acres, with approximately five of those species being threatened. In maintaining this diversity, these lands deliver $9.7 billion a year in value.

Kyle Manley and Jen Christiansen

The regulation of water flows is another vital, though invisible, service that ecosystems on public lands perform, providing more than $31.4 billion in this analysis. By storing precipitation and snowmelt, moderating floods, maintaining base flows, recharging aquifers and regulating water quality, these ecosystems sustain life downstream. A rough analysis of the National Watershed Boundary dataset, particularly the population dependent on watersheds (not including Alaska because of data constraints), shows that more than 21,000 watersheds intersect these lands, with an average of 6,000 people depending on each one. Dependence peaks in Arizona (which has 16,400 dependents per watershed), California (15,600 dependents per watershed) and Nevada (4,500 dependents per watershed). This high dependence is unsurprising considering that much of the Western U.S. water supply originates in high-elevation, snowmelt-dominated headwaters, particularly in the Rocky Mountains.

Our ecosystems also filter pollutants, such as particulate matter, carbon monoxide and ozone, out of our atmosphere and provide clean air to billions of people globally. This service is particularly important in view of estimates that air pollutants caused by fossil-fuel combustion alone are responsible for more than eight million premature deaths every year. The lands that were proposed for sale contribute air-quality regulation valued at $29.5 billion annually.

Additionally, these places give the public opportunities for recreation and tourism, which is estimated to generate more than $11.6 billion a year within the lands suggested for sale and an extra $25.7 billion if you add the aesthetic value they offer. They include ecosystems within some of the most popular and iconic national forests and BLM lands, such as Nine Mile Canyon, Behind the Rocks Wilderness Study Area, White River National Forest, Deschutes National Forest, Tahoe National Forest and Angeles National Forest.

Nearly 83 percent of Alaska’s Chugach National Forest, including Ptarmigan Lake, would have been eligible for sale under the provision.

Analysis of the national digital trails and recreation information databases shows that these landscapes alone contain nearly 56,500 miles of trails, almost 2,000 recreational facilities and more than 300 designated recreational areas. Together they provide 10,000 recreational opportunities made up of 93 activities, including hiking, camping, fishing and hunting. These spaces for sport and relaxation and enrichment and creativity are cherished by the American public and international visitors, contributing as they do to our health and well-being and sustaining the many rural recreation-dependent communities across the Western U.S.

A straightforward, data-driven look at this proposed sell-off reveals its real intent—and its casualties. The administration wants to sell out our lands to corporations for profits. Proceeds from the proposed sale of these lands would have paid for tax cuts benefiting mainly the ultrawealthy. For the average person, it would’ve been a terrible deal. These hundreds of millions of acres of public land are neither accessible nor safe enough to solve our affordable-housing crisis: most parcels lie hours from any urban center, and their wildfire risk is enormous. If development somehow ever happens on these lands, it won’t house working-class families but will line the pockets of corporations and speculators, effectively imposing a regressive tax on the rest of us. What stands to vanish isn’t “barren wasteland,” as advocates for selling public land often describe it, but vibrant ecosystems buzzing with diversity that deliver hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of vital services to the public every year. Far from solving the housing squeeze, this plan would deepen inequality and erode the very ecological systems that sustain us.

Value is an ambiguous term. For the corporate and political class backing this sell-off, it boils down to whatever raises next quarter’s gross domestic product. But for the rest of us, it encompasses the clean water, abundant food, ecological stability, cultural heritage, opportunity for future generations and sheer awe these landscapes provide.