More than 100 years ago Hungarian-born mathematician George Pólya found himself trapped in a loop of social awkwardness. A professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, he enjoyed solitary strolls through the woods outside the city. During one of these rambles, he walked by one of his students and the student’s fiancée. Then, sometime later, still roaming aimlessly, he bumped into the couple again. And then later he did so yet again.

Writing about the experience in an essay published in a 1970 book, Pólya recounted, “I don’t remember how many times [this happened], but certainly much too often and I felt embarrassed: It looked as if I was snooping around which was, I assure you, not the case.”

Desperate to clear his name as a lurker, Pólya did what any good mathematician would do: he generalized the problem. Are two wanderers mathematically destined to cross paths? His original formulation simplified the picture by considering only a single walker on an infinite grid. Every second, the walker chooses a compass direction at random, independent of previous steps. Pólya’s mathematical aim was to determine the probability that the walker would eventually return to their starting point. This answer turns out to be equivalent to the probability that two walkers who start at the same location will ever meet again. He found that if a walker roams forever, they will return to their starting place.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The answer not only absolved him but also revealed a fundamental divide in how the laws of chance interact with physical space. Pólya’s calculations showed that on a two-dimensional surface (such as a forest floor), a random walker is destined to return to their starting point—but in a three-dimensional space, that person is more likely to never return to the starting point. The discovery crops up across chemistry and biology, even explaining how certain molecules efficiently find the appropriate receptor on cell surfaces.

As described in the 2019 fifth edition of Probability: Theory and Examples, by Rick Durrett, mathematician Shizuo Kakutani captured the theorem with a witticism: “A drunk man will eventually find his way home, but a drunk bird may get lost forever.”

Here “drunk bird” refers to not a buzzed buzzard but a random process on a three-dimensional grid (imagine a jungle gym). Every second, the bird chooses from north, south, east, west, and up or down, at random, independent of previous choices. Pólya proved that if you walk forever at random through an infinitely sprawling city grid, then you not only will be guaranteed to return to your starting spot but also will hit every spot on the grid an infinite number of times. If, however, you conduct the same process on an infinite jungle gym, you will have a nearly 66 percent chance of never returning to your starting point. Likewise two wanderers on a jungle gym may never meet, but two wanderers on a flat surface must meet an infinite number of times—Pólya didn’t lack social grace; he lacked a third dimension to escape into.

Even the one-dimensional case, which behaves mathematically like two dimensions, has real-world implications. Imagine rolling up to a casino with $500 in your pocket. A table offers a game with 50–50 odds of winning (better than you’ll find at Monte Carlo). If you keep playing, no matter what betting strategy you use, you will go bust eventually. That’s because we can model the game as a random walk on a number line. You start at 500, and after each round of play, you move either right or left on the line with an equal chance. Pólya tells us that, just as in the two-dimensional case, if you play for long enough you will inevitably explore the entire number line. This includes 0, at which point you’ll go bankrupt. Mathematicians call this “the gambler’s ruin,” and it explains why they’d recommend quitting while you’re ahead or, better yet, not playing at all.

Why do random walks sharply change character between two and three dimensions? Although three dimensions naturally offer more space to roam than two, that alone doesn’t suffice as an explanation. After all, two dimensions offer more space than one, yet both exhibit the same behavior.

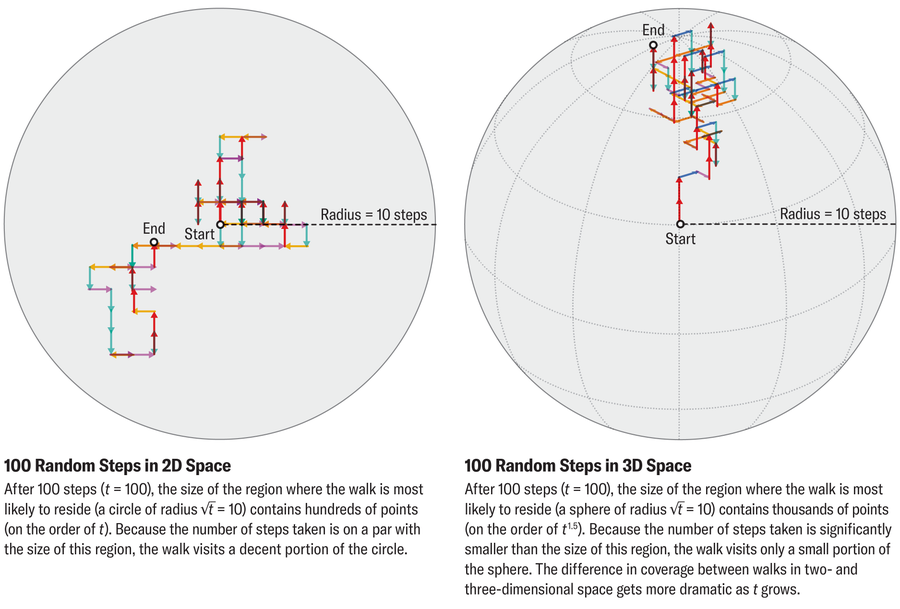

If you take a random walk for some finite number of steps that we’ll call t, then you typically won’t stray farther than √t (the square root of t) away from the origin. In concrete terms, after 100 steps, most walkers will be found within just 10 steps, or √100, of the start. Intuitively, random walks tend to hover near the origin because successive steps can cancel each other out (a walker who takes an eastward step followed by a westward step hasn’t progressed at all). Mathematically, √t equals the standard deviation (a statistical measure of how spread out a set of values are) of the distance from the origin of a t-step random walk.

In other words, if many separate walkers all begin at the same place and roam independently, then the plot of their distances from the origin after t steps would look like a bell curve centered at 0 and with the standard deviation √t. Deriving the standard deviation for the one-dimensional case is an approachable exercise if you’ve taken a statistics class—give it a try.

This √t figure holds in every dimension and is the key to understanding Pólya’s theorem. Think of it like the radius of the region a walker will explore in t steps. This radius has wildly different implications in different dimensions because the number of dimensions determines whether we’re talking about length, area or volume. A line segment with the radius √t has a size on the order of √t; a circle with the radius √t has a size on the order of t (the area of a circle is proportional to the radius squared); and a sphere with the radius √t has a size on the order of t1.5 (the volume of a sphere is proportional to the radius cubed).

But regardless of dimension, a walker taking t steps cannot visit more than t distinct points. In one dimension, the number of steps exceeds the size of the region explored (t > √t), forcing the walker to retrace their steps constantly. In two dimensions, the number of steps matches the region’s size (t = t), allowing the walker to eventually cover the grid, albeit thinly. But in three dimensions, the space is vast compared with the number of steps (t < t1.5), leaving most points unvisited and the origin unlikely to be revisited.

Of course, the real world rarely resembles a perfect grid, and birds don’t flip coins at every wingbeat. Still, this contrast between two- and three-dimensional walks has surprisingly practical stakes in the natural sciences. One compelling example involves how chemicals react in our body. Researchers often use random walks to model molecules diffusing through another substance. Consider a hormone trying to find a specific receptor on a cell’s surface. It doesn’t have a homing mechanism, so such reactions happen through chance encounters.

The hormone could wander aimlessly through the three-dimensional fluid around the cell until it bumps into its target. Instead many molecules bind loosely to any point on the cell membrane first. Once attached, they slide across the two-dimensional surface of the membrane until they hit their target. This reduction of dimensionality turns a slow three-dimensional walk into an efficient two-dimensional one.

Next time you run into someone you’re avoiding, try to turn the encounter into a profound mathematical insight. It sure beats hiding behind a tree.