This fossilized vomit is older than the dinosaurs

Vomit is gross—but 290-million-year-old vomit is a scientific marvel

An artist’s rendering of Dimetrodon teutonis vomiting; two of the smaller reptilian animals found in the regurgitalite are depicted in the scene as well.

Fossils are remarkable for their ability to viscerally connect us with long-lost life. The bulk of a Tyrannosaurus rex skull, the biting point of a shark tooth, the startling familiarity of a hominin footprint—and then there’s the charm inherent to any sample of regurgitalite, the paleontological term for fossilized vomit.

Okay, charm might be a stretch, but to the right scientist, the rare finds are “little treasures,” says Arnaud Rebillard, a Ph.D. candidate in paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Berlin. Consider the regurgitalite that’s the focus of research that Rebillard published on January 30 in Scientific Reports—the oldest known regurgitalite from a terrestrial ecosystem.

Found in 2021, the specimen comes from a 290-million-year-old German site called Bromacker. Over a century of excavation, paleontologists have glimpsed a valley full of conifers that were apparently teeming with vegetarians, says Amy Henrici, a retired Carnegie Museum of Natural History paleontology collection manager, who was not involved in the new research.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

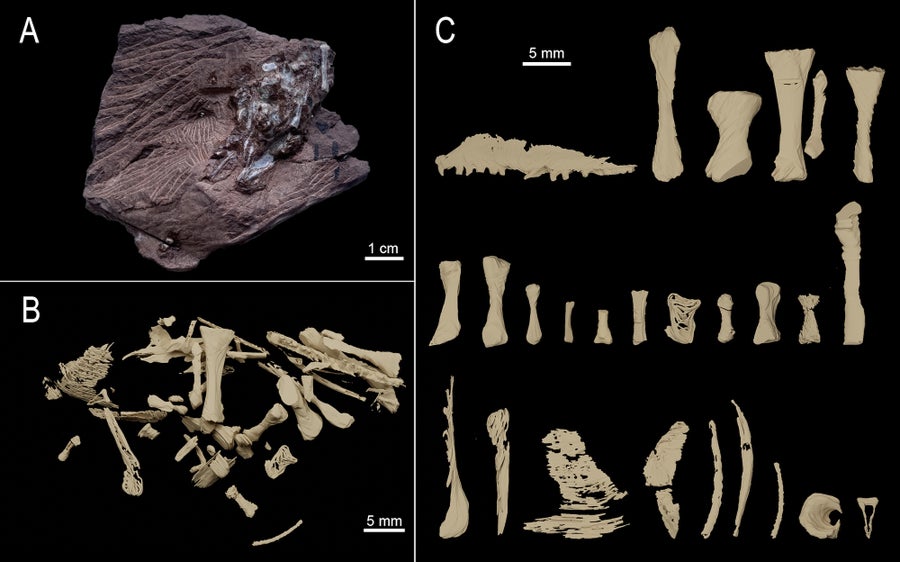

Amid the loose fossils and remarkably preserved skeletons that characterize the site, the regurgitalite was uninspiring—until, that is, the fossil cleaning process and a computed tomography (CT) scan offered a clearer view. That process digitally extracted a cluster of 41 small bones that turned out to belong to three separate species: two small reptiles and a larger reptilelike animal.

Image of the regurgitalite (upper left), a digital analysis showing the location of bones within the fossil (lower left), and an image showing those bones separated out (right).

“This was clearly something that was eaten and then ejected from an animal,” Rebillard says. The next questions were obvious: Which end did the fossil hail from, and what kind of animal expelled it?

The most famous counterparts of regurgitalites are coprolites, or fossilized feces. (There are also gastrolites and cololites, which preserve a digestive tract’s contents in place in the stomach and intestines, respectively. Together these types of fossils are known as bromalites.) Distinguishing between coprolites and regurgitalites is “actually not super obvious all the time,” Rebillard says.

In this case, two pieces of evidence led Rebillard and his colleagues to conclude that the remnants had been vomited up: the leg bones of the largest prey animal remained connected to each other, suggesting that the limb had not traversed an entire digestive system. And the material directly surrounding the bones was low in phosphorus, which is plentiful in fossils that were once poop.

As to whose mess the scientists were pondering, there are two species known from the Bromacker site that would have been large enough to eat animals of the size found in the regurgitalite: Dimetrodon teutonis (a tiny member of a sail-backed group of animals that are often mistaken as dinosaurs) and Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus. Both contenders are synapsids, or members of a group that includes mammals and their extinct relatives, and would have measured around 20 to 30 inches long without their tail.

Whichever predator was involved, Henrici notes that the regurgitalite confirms that one of these animals snacked broadly on the smaller critters around it and could vomit up indigestible material, much as modern owls and Komodo dragons do today. For Rebillard, the fossil is also proof that all three prey species not only lived together in the same geologic time but also died together in the same week or even day.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.