Longing for the past? You’re not alone, and chances are, the place you’re missing is by the water. A new study found that “blue” landscapes like beaches, rivers and lakes are powerful nostalgia triggers that also boost psychological well-being.

The Collins English Dictionary defines nostalgia as “an affectionate feeling you have for the past, especially for a particularly happy time.” Although it can be bittersweet, nostalgia tends to evoke in people memories of a time long past that is both uniquely pleasant and irretrievable.

A new study led by the University of Cambridge in the UK has explored the physical places that people feel nostalgic about, the features those places have, and how reminiscing about them impacts our mental well-being.

“We expected people to be more often nostalgic for green places since so many studies emphasize the psychological benefits of green, natural environments,” said Elisabeta Militaru, who led the study as part of her PhD at Cambridge’s Psychology Department. “We were surprised to find that blue places are the hallmark feature of place nostalgia.”

The researchers conducted three studies with over 1,000 participants from the UK and the US to gain answers to three questions: 1. What kinds of places trigger nostalgia? 2. What do people feel when they recall these places? And 3. What psychological effects do those nostalgic memories have?

“The idea that places serve as an emotional anchor is not new,” Militaru said. “Nearly 3,000 years ago, Homer wrote of Ulysses’ longing to return to his homeland, Ithaca. We wanted to understand what makes certain places more likely to evoke nostalgia than others. What are the physical and psychological features that give a place its nostalgic pull?”

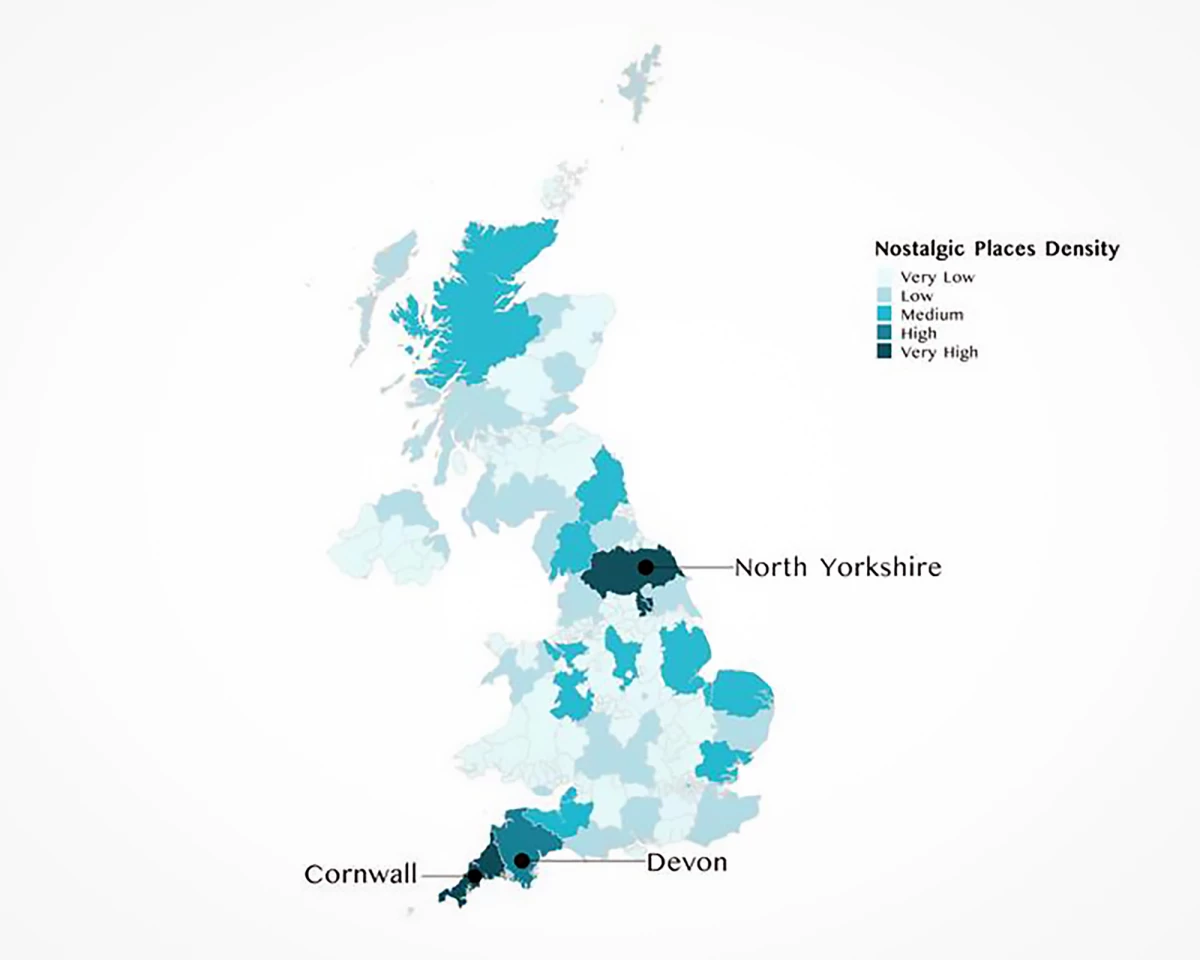

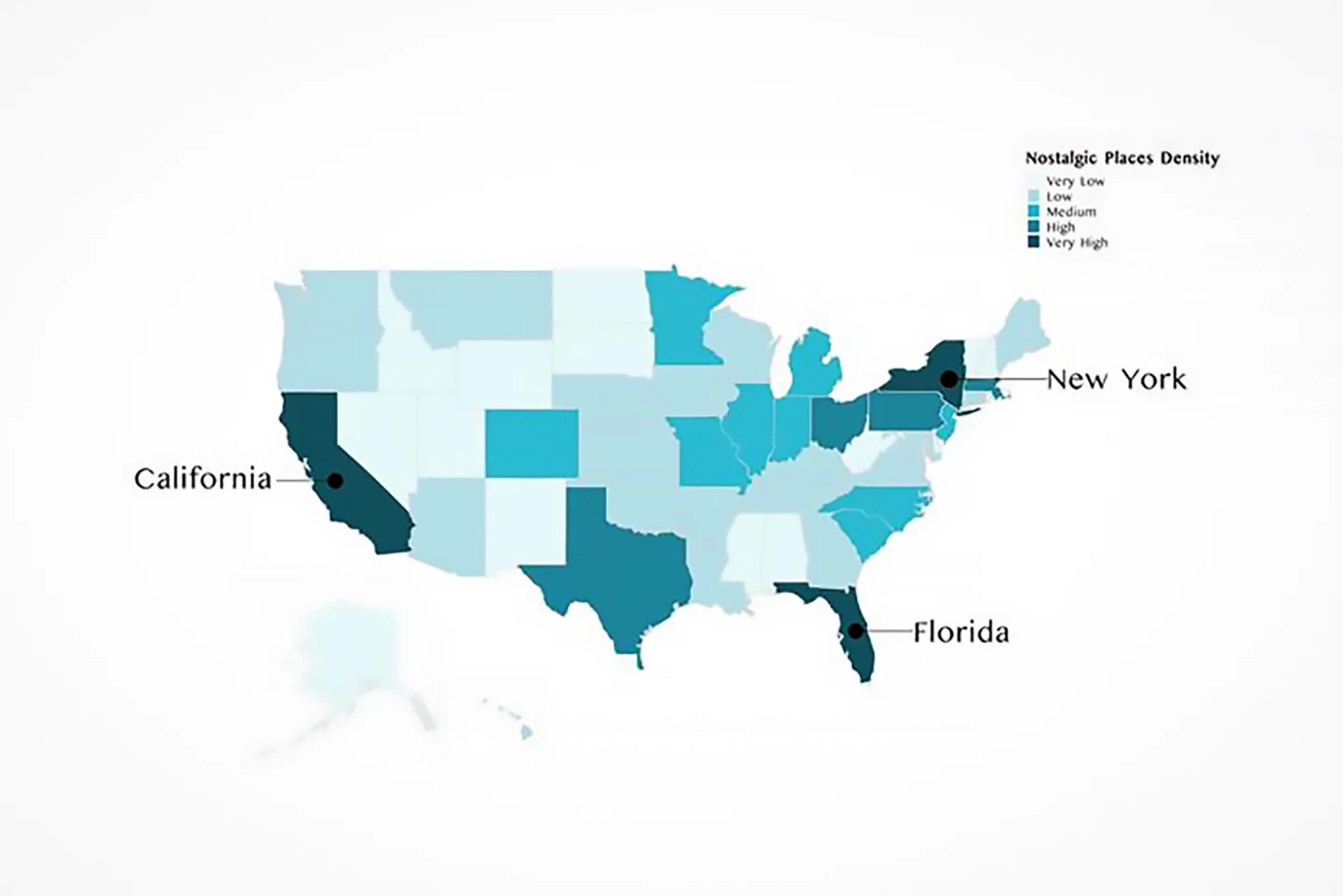

University of Cambridge/Dr Elisabeta Militaru

In Study 1, 200 individuals from the UK were asked to provide a written description of a place they felt nostalgic about and categorize its landscape as either oceanside, seaside, lakeside, riverside, urban, agricultural, forest, grassland, shrub, wetland, or permanent snow. Second, they indicated the size of the place (e.g., room, neighborhood, city). Third, they stated the number of people living there. A linguistic analysis tool assessed whether their descriptions were more positive or negative emotionally. The researchers found that the most frequently mentioned nostalgic places were in “blue” landscapes such as the seaside, riverside, or lakeside. These places were often medium-sized, like a town or neighborhood, and sparsely populated. Participants used more positive than negative words to describe them.

In Study 2, 398 US participants were asked to recall either a nostalgic or an ordinary place and pinpoint it on a map. Researchers then looked at how far these places were from where participants ordinarily lived, whether they were near water, and how people described them. They also measured the emotional effects of thinking about these places. Nostalgic places were more likely to be located by water and physically far away, although they felt psychologically close to participants. Thinking about these places increased feelings of social connectedness and a sense of meaning in life.

Study 3, which involved 403 US participants, expanded on the previous study by adding green vs. gray landscape ratings, measures of temporal distance (that is, how long ago the visit happened), and additional psychological benefits of self-continuity, self-esteem, and authenticity. Self-continuity is a stable sense of self across time. The researchers found that nostalgic places were bluer, greener, and less gray than ordinary places. They were more physically and temporally distant, but felt closer emotionally. Recalling these places boosted participants’ self-continuity, self-esteem, and authenticity, or a feeling that they were being true to themselves.

One explanation for why blue landscapes evoke stronger emotions lies in their visual structure. The researchers suggest that the fractal nature of blue landscapes, that is, their self-similar patterning and the way their component parts resemble the whole at different scales, contributes to their high nostalgia rating.

University of Cambridge/Dr Elisabeta Militaru

“Past research suggests that landscapes with moderate fractal structure, like coastlines, tend to generate positive emotions,” Militaru said. “People don’t like extremely chaotic outlines of the kind you might see in the middle of the forest, where you don’t get a sense of openness.

“People also don’t like too little complexity. With an urban skyline, for instance, there are very few breaks in the scene’s pattern. Seaside, rivers and lakes may give us the optimal visual complexity, but more work is needed to fully understand this.”

The study might seem somewhat whimsical, but its findings have important real-world implications. Designing, or redesigning, cities with more accessible “blue” and “green” spaces could support emotional well-being, not just through aesthetics, but by encouraging meaningful, memorable experiences. Place-based reminiscence therapy could be tailored for people experiencing loneliness or social disconnection by focusing on emotionally significant locations.

“Now we know that nostalgia is a psychological resource; it emerges when we are faced with psychological discomfort, like feeling lonely or socially excluded,” said Militaru. “Emerging research finds that nostalgia can also have a positive role in caring for people with dementia.”

“Our research suggests that access to coasts, rivers, parks, and natural landscapes should be prioritized, especially in dense urban areas,” Militaru added. “Communities need to be involved in urban planning decisions implemented in their neighborhoods. Only then can we identify the local landmarks that need to be preserved.”

The study was published in the journal Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology.

Source: University of Cambridge