Not all probiotics are created equal. A new study found that one commonly available strain made a gut infection worse, while another helped stop it in its tracks, thanks to a powerful natural antibiotic and an unexpected ally from the gut’s own ranks.

Probiotics, a collection of “good bacteria” in a capsule or gummy, are commonly used to replenish the gut microbiome after a period of antibiotic treatment, which tends to knock out good and bad bacteria indiscriminately. But given the range of probiotic supplements out there, do they all have similar effects?

A new study by researchers from North Carolina State University (NC State) has investigated the effects of two common probiotic strains, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus gasseri, on mice that were given antibiotics and then exposed to C. difficile, the bacterium responsible for causing antibiotic-associated diarrhea.

“Colonization resistance or the ability to prevent colonization of pathogens is a function of a healthy microbiota,” said Casey Theriot, PhD, professor of infectious diseases at NC State and the study’s co-corresponding author. “This study looked at how long it took resistance against C. diff colonization to return after antibiotics and the impact of two of the most commonly used strains of Lactobacillus probiotic on that return.”

The researchers wanted to see whether these two probiotic strains helped or harmed gut recovery and whether they could prevent C. difficile infection. Mice who’d been treated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic were divided into three groups. One group received L. acidophilus, one received L. gasseri, and a third acted as a control group, receiving no probiotic strain. Each group was administered C. difficile weekly for four weeks, and their microbiota was examined to measure bacterial load and C. difficile resistance.

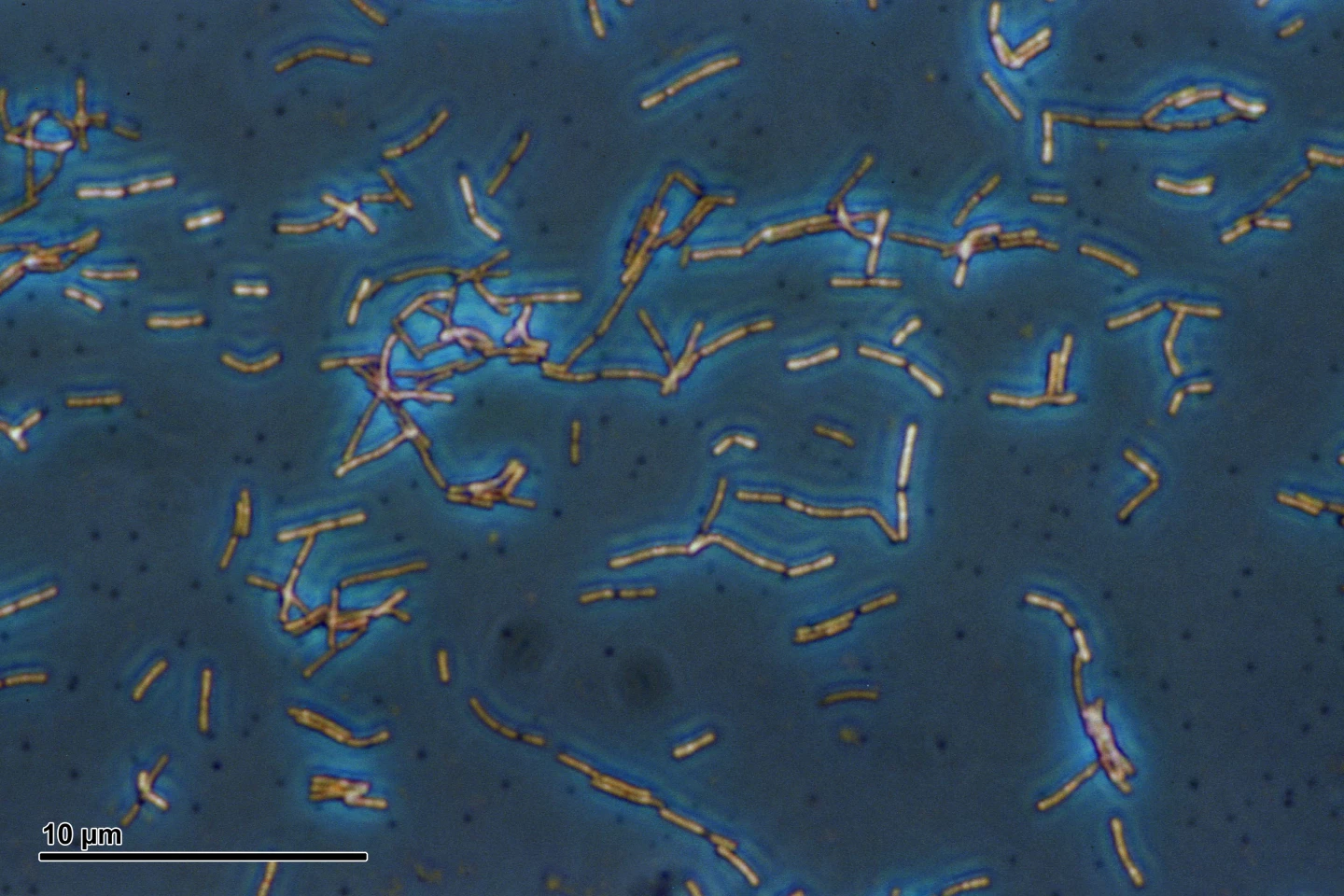

Mice that received L. acidophilus had higher levels of C. difficile, more bacterial toxins, and slower recovery of gut resistance. On the other hand, mice that received the L. gasseri strain had reduced C. difficile levels, and it helped restore the gut’s natural defenses more quickly. This probiotic produced a bacteriocin, a kind of potent natural antibiotic produced by bacteria, that directly inhibited the C. difficile bacterium. Interestingly, even after L. gasseri was no longer detectable in the mice’s gut, its positive effects persisted.

What’s more, the strain coincided with a bloom in Muribaculaceae, a potentially beneficial gut bacterial family, raising the possibility that it promoted conditions favorable to their growth. Muribaculaceae appeared to indirectly help resist C. difficile, possibly by outcompeting it for nutrients. Experiments showed that two species, Muribaculum intestinale and Duncaniella muris, can restrict C. difficile growth under laboratory conditions.

“We have always known that it’s important to understand the strain-specific impact of probiotic strains,” said the study’s other corresponding author, Rodolphe Barrangou, PhD, Distinguished Professor in Probiotics Research in NC State’s Department of Food, Bioprocessing and Nutrition Sciences. “Depending on the condition and composition of the individual’s microbiome, the disease, and the probiotic strain, you will have different effects and outcomes.

“What’s interesting is that this study indicates it’s more complicated than people think, because probiotics can have transient or indirect effects on the microbiome. L. gasseri doesn’t prevent infection, it transiently promotes recovery of microbiome through Muribaculaceae, which subsequently could provide resistance. This opens new avenues to inform what we should do next.”

There are limitations to the study. It was conducted in mice, which, while informative, may mean the results don’t directly apply to humans. Also, only a single probiotic dose was used, whereas real-world use often involves repeated or long-term dosing. And the results may not extend to other strains of the same species. The study also followed mice for four weeks, so longer-term effects, including microbiome stability and risk of reinfection, remain unknown. And some of the microbial changes, like the bloom in Muribaculaceae, could have occurred randomly rather than as a direct result of probiotic action.

Nonetheless, the study’s findings challenge the blanket assumption that probiotics are always helpful after antibiotics. Further research is needed to expand our knowledge of the effects of probiotics on the gut microbiome.

“This is the only study out there that is functionally testing resistance in the microbiome,” Theriot said. “Although this work is in a mouse model, it shows the need for better mechanistic understanding of how probiotics affect the microbiome, because not only can they have effects weeks after they’ve left the body, in certain situations they have the potential to prolong or complicate recovery.”

The study was published in the journal Human Microbiome.

Source: NC State University