‘Baby cluster’ of galaxies may challenge cosmic models

Dating to only a billion years after the big bang, JADES-ID1 may be the earliest, most distant galaxy protocluster astronomers have ever seen

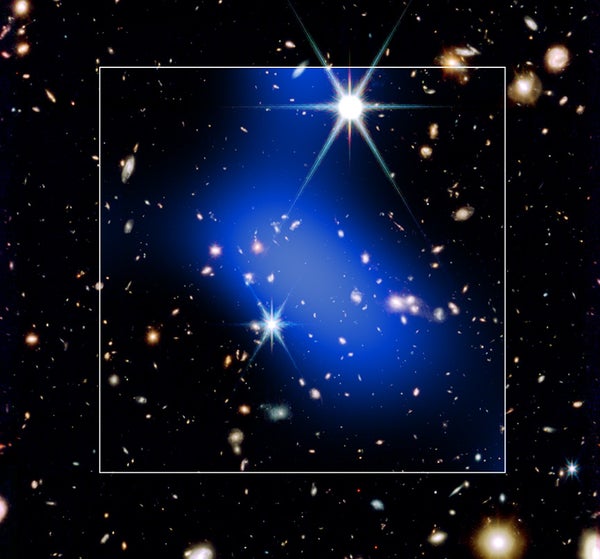

A composite infrared and x-ray image of JADES-ID1, a growing protocluster of galaxies seen about a billion years after the big bang. The white box shows the view of the Chandra X-ray Observatory (blue) overlaid on an infrared image from the James Webb Space Telescope.

X-ray: NASA/CXC/CfA/Á Bogdán; Infrared: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/P. Edmonds and L. Frattare

Astronomers have spotted a mysteriously mature “baby cluster” of galaxies in the early universe, scarcely a billion years after the big bang. Although not a full-grown, full-blown galaxy cluster, the protocluster is still bigger and more developmentally advanced than most models can easily explain—and also may be the most distant ever seen. Unveiled using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the protocluster’s strange stature was announced last week in a study published in Nature.

“Clusters of galaxies are often referred to as at the ‘crossroads’ between astrophysics and cosmology,” says Elena Rasia, an astrophysicist at the University of Michigan, who was not part of the work. They’re natural laboratories for studying how galaxies interact and how supermassive black holes grow. Tracking how clusters assemble across vast stretches of time and space also informs our knowledge of the cosmic web and the cosmological parameters that shape it. This so-far-unique protocluster, Rasia says, could be important from both perspectives.

Called JADES-ID1 for its location within the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES), the protocluster was first reported alongside about two dozen other early-universe candidate objects in a separate study published last year. JWST data suggest JADES-ID1 contains at least 66 young galaxies, and this latest study measures the protocluster as being some 20 trillion times more massive than our solar system. Most of that mass is in the form of invisible dark matter, but as revealed by Chandra, the protocluster is also embedded in an enormous cloud of hot gas aglow with x-rays.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Chandra data were crucial for confirming the protocluster is genuine, says lead study author Ákos Bogdán, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. Drawn in by a galaxy cluster’s immense gravitational field, infalling gas piles on and generates shock waves, heating up to millions of degrees and creating the x-ray glow; astronomers call this diffuse intergalactic “atmosphere” the intracluster medium, and it’s typically a sign of a mature, settled-down system. For JADES-ID1, however, it’s showing instead a baby cluster rapidly growing by gobbling up surrounding gas—about two billion years before the previous record-holding x-ray-bright protocluster burst on the cosmic stage.

JADES-ID1 “is really the youngest cluster with an x-ray-emitting atmosphere,” Bogdán says. “And this discovery pushes the x-ray protocluster frontier to much, much earlier times than prior examples.” Given the inferred enormous mass of JADES-ID1 and the very small patch of sky astronomers surveyed to find this object, he adds, “we either got extremely lucky [to see it] or we are catching a region of the universe that grows unusually fast.”

Standard models of cluster formation predict that something so big shouldn’t exist so early in the universe’s history. And, assuming it continued its prodigious growth further forward into more recent cosmic epochs, JADES-ID1 would eventually become an anomalously oversized full-grown galaxy cluster. But whether this bulky protocluster’s existence actually demands the rewriting of textbooks remains to be seen.

“It’s true we don’t understand fully how such structures can form and appear so advanced so early in time,” says Klaus Dolag, a computational astrophysicist at Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, who was not part of the JADES-ID1 studies. But, Dolag adds, “we may have already some indication what is happening here.”

In a study from 2023, Dolag and colleagues performed robust simulations of protocluster assembly only about a half-billion years later than JADES-ID1, finding that many of those virtual objects developed detectable x-ray atmospheres by that time. But of the 2023 study’s largest, earliest protoclusters, none went on to become supersized galaxy clusters as the simulation progressed into the modern-day universe. Instead their growth slowed as they matured and exhausted available reservoirs of surrounding gas. If the same behavior holds true for JADES-ID1, Dolag says, its observed early, hefty size would be less mysterious.

Stefano Borgani, an astrophysicist at the University of Trieste in Italy, who was not part of any of these studies, notes that because detecting the x-rays from JADES-ID1 and other early protoclusters pushes Chandra to its limits, it’s hard for researchers to gauge what they really know about these extreme systems. “A clearer understanding of whether [JADES-ID1] challenges our current understanding of cosmic structure formation will need to await a next generation of x-ray telescopes” with Chandra’s sharp vision but with greater sensitivity, he says.

Bogdán agrees that astronomers need to study additional protoclusters of similar vintage. “The next steps should be to find more systems like this and build bigger samples of protoclusters in the early universe so that we’re not relying on a single object,” he says.

Resolving the mystery of this mature baby cluster will yield important breakthroughs no matter what, Dolag says. “Either we learn something new about the complex interplay of various physical processes shaping the formation of galaxies—or we learn there is indeed a flaw in our general background model of cosmology causing us to oversimplify.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.