Culture

/

Books & the Arts

/

October 14, 2025

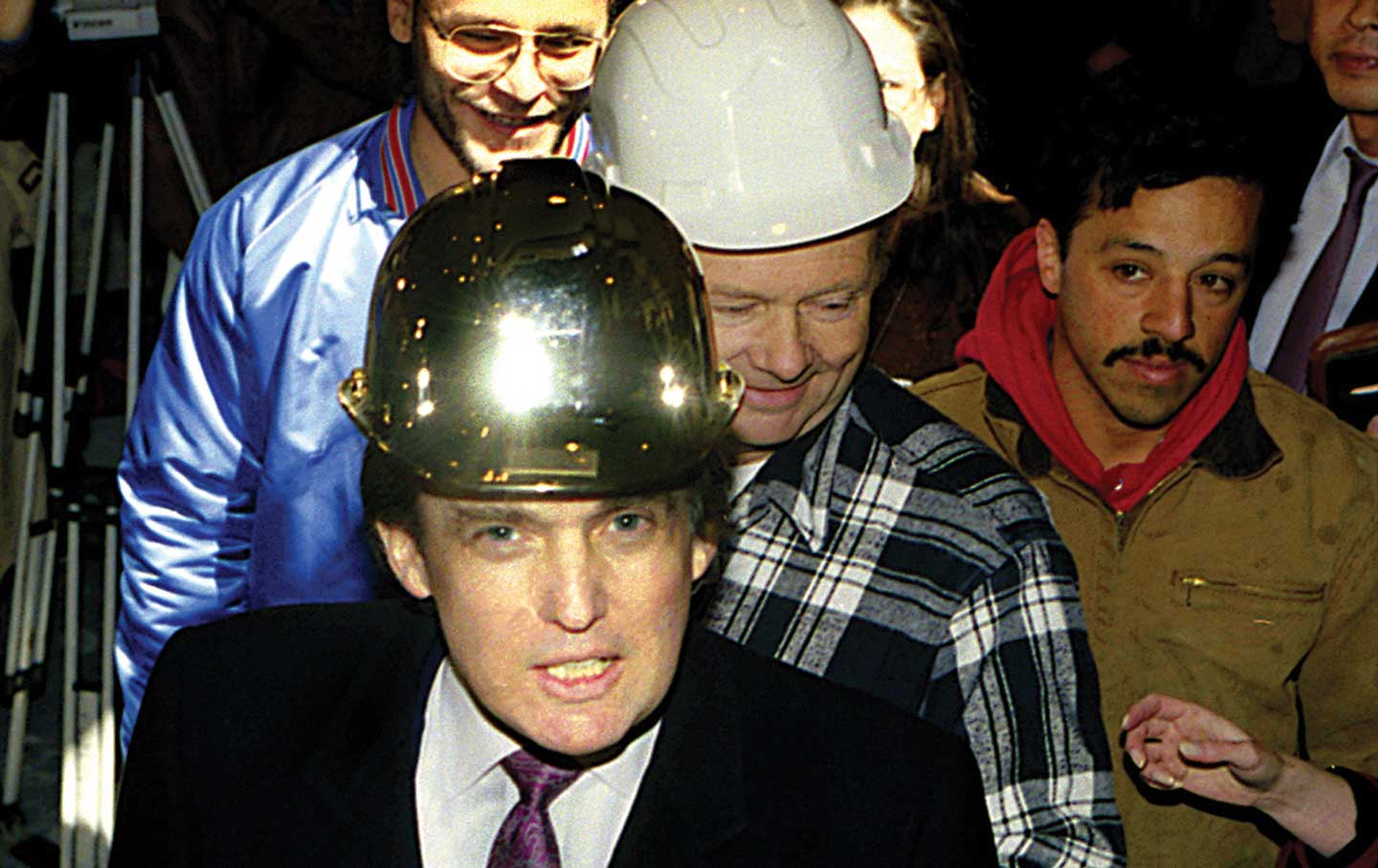

Trump’s theory of politics.

The proliferation of privately held companies during the Reagan years laid the foundations for Trump’s approach to government.

Ever since Donald Trump’s election in 2016, liberals and the left have struggled to understand the meaning of his rise, and that of “Trumpism,” for American politics. When Trump entered the political scene, he was hard to take seriously. In his first campaign, he seemed—initially, at least—to be a zombie headline straight from the New York Post’s“Page Six”: a faded reality-TV star, a bankrupt real estate speculator, a huckster, a creep, and a punch line. Even after he won the election, many liberals refused to recognize that he was all of those things and also the president of the United States. Having placed their hopes in Hillary Clinton, they marched to slogans like “Not My President.” Trump might be in the White House, but it was unfathomable to view him as an enduring threat. Sure, he spoke for a large minority of Americans—the prejudiced, the left-behind, the economically disadvantaged white working class, the “deplorables” (to quote Clinton herself) who were having trouble adapting to changing racial, ethnic, and sexual norms. Trumpism was a remnant of reaction, an eruption from the past. Accordingly, after 2020, many liberals, and even some on the left, came to the reassuring conclusion that while Trump and Trumpism had been a troubling interregnum, they had been supplanted by a new liberal age—a return to reason, normalcy, and science with Joe Biden at the helm. Pundits depicted Biden as the second coming of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, implying that his election would usher in a new era of public investment and social tolerance.

Books in review

Counterrevolution: Extravagance and Austerity in Public Finance

Then Trump won again. If the first time, he’d lost the popular vote while winning the Electoral College, now no one could deny that he was the legitimate victor and that the coalition he spoke for seemed to be growing—in 2024, Trump was able to command the popular vote and to make strides with Black and Latino voters as well. The quandary of understanding Trump, not as an electoral accident but as something more, has returned with a vengeance. Trump’s actions in office the second time around have made matters still more complicated. On one level, over the past 10months, Trump has acted like any other Republican of the past 50 years, pressing on with the party’s long-standing agenda. He has defunded essential welfare programs; he has slashed government spending and undermined government agencies; he has cut taxes for the rich. But in his aggressive use of ICE against immigrants, his campaign against trans people, his sabotage of basic science, his nationalistic belligerence, and his willingness to use government authority against private universities to make them subject to his will, he goes well beyond the conventional free-market Republican mainstream. All of this raises the question: Are Trump and Trumpism best understood as the consolidation of an elite economic program, as a nostalgia-laced brew of prejudice and rage, or as a coherent, forceful new style of authoritarian rule—and if it’s the latter, why is this happening now? How has this politics not only made its way into the center of American power but with a near majority, too? Making sense of all this is not just an abstract exercise; it raises important questions about what kind of politics the left will need to counter the nightmarish course we seem to be hurtling along.

When Melinda Cooper wrote Counterrevolution: Extravagance and Austerity in Public Finance, she could not have anticipated Trump’s return to the White House or the political and intellectual dilemmas it would pose. But Counterrevolution does offer a new way of seeing Trump: It situates him as part of a larger shift in how people generate and preserve wealth, a change in the country’s underlying political economy. Whether one agrees with it or not, it offers a striking explanation for how the left might interpret the emergence and persistence of Trumpism.

Cooper argues that the American political economy in the 21st century has been defined by extreme wealth inequality and also, less noted, the accumulation of massive private fortunes. Often, people on the left have blamed neoliberalism— especially deregulation and upper-bracket tax cuts—for the income gap, and Cooper does too. But she goes farther, arguing that government austerity in the public sphere (cuts to welfare-state spending) has been accompanied by policies that encourage financial speculation through low interest rates and the practice of quantitative easing, in which the Federal Reserve uses its prerogatives to effectively support the prices of stocks and other assets.

In many ways, none of this is new. Extremes of wealth and poverty are hardly novel in the history of the United States. But Cooper points to an important difference: If, in much of the 20th century, these economic divisions were produced by major industrial corporations, collectively controlled by a community of shareholders and stock owners that included pension funds, banks, and wealthy individuals, then in today’s economy they are produced by private equity funds, financial firms, family trusts, and tech firms owned by a handful of wealthy founders.

Many commentators have been struck by the crude ideological agenda of Project 2025 (especially in regard to gender), the ferocity of Trump’s nationalism, the relentlessness of his self-promotion, and the strange combination of wheeling and dealing and brute force that Trump seems to believe qualifies as governance. But Cooper’s book clarifies that along with these cultural and stylistic qualities, there is another aspect of Trump and Trumpism that often gets overlooked: What is most distinctive about both is that they reflect the unique characteristics of a political culture and economy shaped by the private wealth and patriarchal whims of a group of entrepreneurs who have been able to wrest free of any of the structural limits that once guided economic life. The financiers, tech bros, and megalomaniacal entrepreneurs of today’s Republican Party are no longer accountable to the bureaucratic corps of middle managers that populated the mid-20th-century corporations or to large numbers of external shareholders. The authority of the private executive over the firm that he owns is echoed in Trump’s habit of governing by executive order, his penchant for making “deals,” and his ability to win the allegiance of tech billionaires like Elon Musk, who also believe in the need to free corporate founders from the hassle of answering to regulators or shareholders. It may even account for Trump’s support from the small-business owners and middle-class voters who decided that they identified more with this style of leadership than with the professional expertise represented by Kamala Harris.

Current Issue

As Trump’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency continues to assault public-sector workers and their jobs even after Musk’s departure, and as Trump’s 2026 budget proposal slashes federal spending by more than 160 million next year—targeting programs for health, education, and housing as well as the National Endowments for the Arts and the Humanities—Cooper’s discussion of the privatized wealth of our age captures an economic dimension to Trumpism that often goes unremarked. Trump’s politics and his appeal are not only inspired by far-right ideologies, culture-war passions, age-old xenophobic prejudices, and a long-standing Republican animus toward the welfare state; they emerge out of a capitalist order that has ceased to be constrained by any of the institutional, intellectual, or professional limits that defined corporate capitalism in an earlier era. This is what sets the era of Trump apart from earlier epochs of conservatism: When Ronald Reagan took office, for example, he sought to remake the economic world by cutting income and capital-gains taxes, weakening organized labor, and deregulating finance in order to restore the profitability of American corporations. Trump, meanwhile, is bringing the norms, ideas, and practices of family business into the operations of the state. For Trump, the United States is just one large, privately held corporation, controlled and dominated by a few people who perceive themselves as able to do whatever they want. No stockholders, no activist shareholders, no debates or discussion, no annual meetings, no publicly released reports, no room for dissent or deliberation—just a tiny group of owners who enrich themselves while the rest of us stand on the sidelines.

Counterrevolution grows out of Cooper’s 2017 book Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism. In Family Values, Cooper maintained that two seemingly contradictory things—free-market ideology and the self-sacrifice of familial bonds (as well as the maintenance of traditional gender roles)—have always been closely related. On the one hand, capitalism depends on the family to school its members in the work ethic and the social norms that will make them responsible and cooperative as workers and provide them with the emotional and material sustenance they need to show up for work each day. More deeply, capitalism simultaneously creates a competitive, consumerist economic culture and a yearning for relationships that are not infinitely fungible and self-interested. This latter wish for solidarity is what the family comes to stand for: Christopher Lasch’s “haven in a heartless world,” a unit intrinsically opposed to the ruthlessness of the economic sphere.

There’s an old line of interpretation among liberals that treats the alliance between Christian conservatives and the Republican Party as manipulative and opportunistic. Conservative politicians use opposition to abortion to lure voters to support a program that is really all about tax cuts. Economics are the priority, culture the loss leader.

Cooper sees a deeper affinity. Neoliberal economic policies tear apart public institutions, labor unions, and other forms of social solidarity that mitigate insecurity and protect people’s livelihoods. As they do, people turn to the family as an alternative—to bonds that are stable and immutable. In this way, ruthless economic competition and ironclad gender norms can in fact be part of the same political program. People are thrust into an individualistic economic sphere, but they can rely on family relationships as a buffer that protects them from the antagonistic world of work. Men, in particular, benefit from the love, support, and self-sacrifice of women.

In Counterrevolution, Cooper carries this discussion of the position of the family in contemporary capitalism farther still. This time, she focuses on its economic importance—specifically how, in a moment of ferocious self-branding, technological change, and outsourcing, the family not only serves as a place of emotional respite but has become a model for a different kind of capitalist enterprise than the one most popular in the 20th century: In place of the bureaucratic, shareholder-owned corporation has come the private patriarchal company.

Cooper’s argument turns on a claim about corporate ownership structures that may strike some readers as arcane, but which she believes is important to understand in order to make sense of the world we live in now. After World War II, the most important companies in the United States were large, publicly traded corporations governed by professional managers, owned by thousands of dispersed shareholders. (Although numerically, the majority of businesses have always been privately owned small firms.) After the New Deal, these publicly traded corporations were overseen by a government entity, the Securities and Exchange Commission, which made sure they were not actively engaged in fraud. During the Cold War, this regulated capitalism flourished. When executives sought to maintain social peace by bargaining with organized labor and supporting social welfare, this was not just a pragmatic political response; Cooper argues that it also reflected the structure of the publicly traded corporation, which is accountable to its shareholders through quarterly reports and annual meetings in a way that a privately held company does not need to be.

During the 1970s and ’80s, Cooper writes, this form of corporate structure and social compact began to come apart. Shareholders and owners, anxious about falling profits, sought to assert their dominance over management. Hostile takeovers and leveraged buyouts made it clear who was really in control, and with them also reemerged an older form of corporate power: the privately held firm in which the owners were directly responsible for managerial decisions, without external oversight. Even when private companies went public, a variety of ownership structures emerged—private equity, venture capital, family trusts—that privileged owners and shareholders and gave small groups of people greater control over the firms, despite the fact that they were publicly traded.

These entrepreneurial executives, Cooper argues, constitute an under-recognized force driving the rise of the Trumpian right: Privately held firms are often much more politically aggressive and may be more likely to pursue the libertarian and culturally conservative politics that publicly held companies avoid. Family dynasties such as the Kochs and the DeVoses (of Amway fame) have been able to pour so much money into libertarian political causes in part because there is no one warning them that doing so might damage the corporate brand. As Cooper puts it, “S&P 500 corporations are not so much ‘woke’ as legally accountable to shareholders and constantly vulnerable to the risk of consumer backlash. Private, unlisted companies and their general partners are far less constrained.”

For Cooper, this change in patterns of ownership is part of a larger transformation of the economy and our political culture that has taken place over the past five decades. But it is also a distinct shift that has helped to create the ethos and worldview of Trump’s political base. Wealthy individuals hailing from the world of private equity, hedge funds, and venture capital, followed by real estate, construction, and oil and gas—all industries studded with large, privately owned companies—have contributed generously to Trump. In 2024, most of the top individual donors to his campaign came from privately owned companies like SpaceX, Hendricks Holding Company (a privately held conglomerate), and Uline Incorporated (which sells shipping supplies).

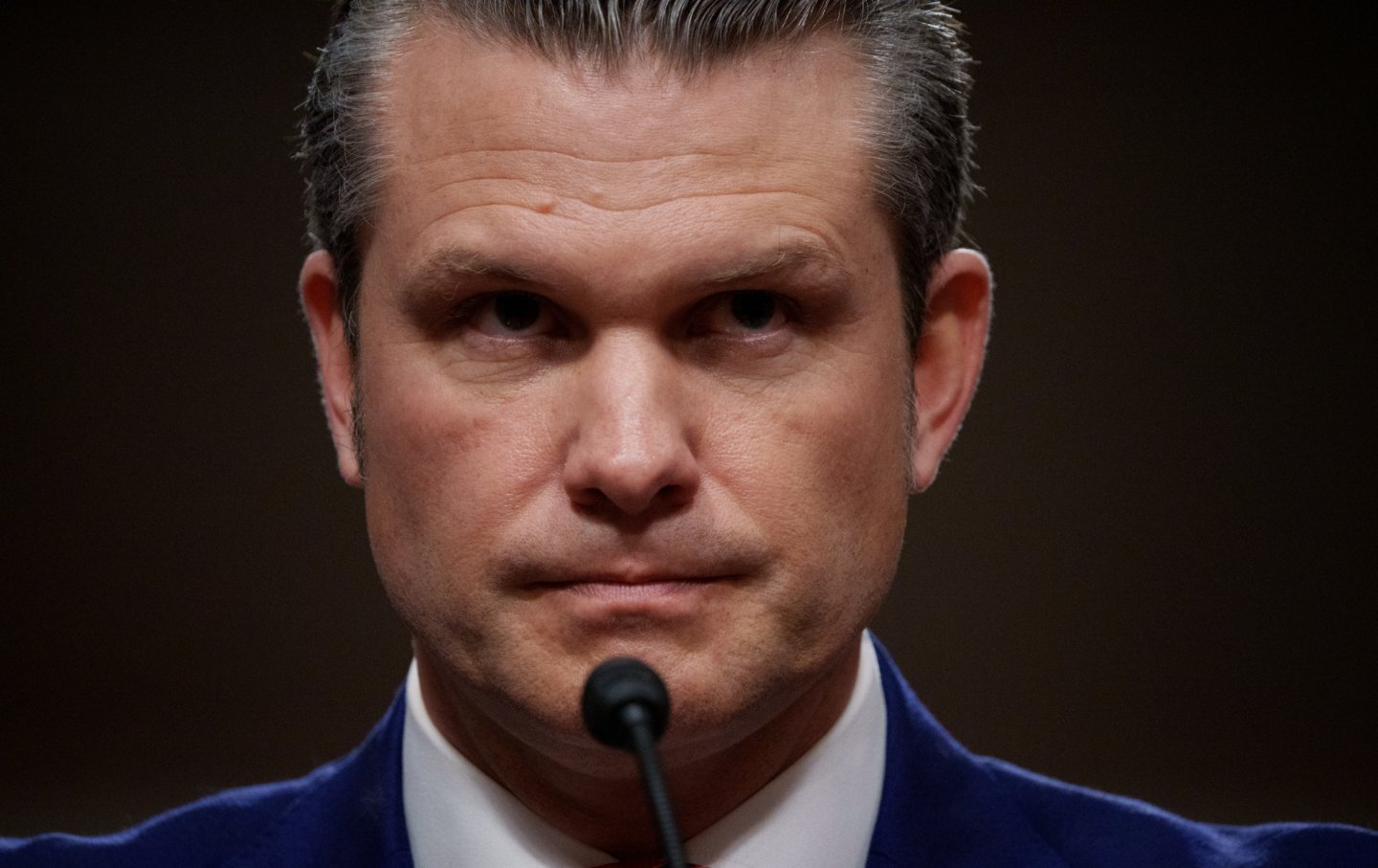

Trump’s first cabinet, in fact, was filled with people from the ranks of private equity, hedge funds, and real estate, from Betsy DeVos (Department of Education) to Steven Mnuchin (Treasury) to Sonny Perdue (Agriculture). Such wealth is even more extremely represented in Trump’s second cabinet, from Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent (hedge fund) to Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick (investment bank Cantor Fitzgerald). And the Trump Organization, of course, is privately owned as well. The Trump administration doesn’t just embody business interests in general—it embodies a very specific kind of business, one in which the patriarch rules. E-mails demanding that workers justify their jobs or face layoffs; scolding and humiliation of underlings who dare to disagree; drastic cuts to programs just because the boss doesn’t like them; arbitrarily lobbing tariffs anywhere he pleases; insisting on payback for those perceived as enemies—these signature Trumpian actions all echo the practices of business owners in their private fiefdoms, who do not have to answer to shareholders or, for that matter, anybody else.

Cooper not only claims that Trump’s ascendance is linked to the shift from an economy led by publicly traded corporations to one in which the most active, forceful public representatives often come from the world of privately held companies; she also suggests that this is an important part of his appeal to the white working class. The question of why Trump won substantial support among white working-class voters has been the subject of much analysis since November. Was it the price of eggs? Implacable racism and xenophobia? Was it that people who lack meaningful power over their own lives found themselves drawn to identify with a strongman, gaining an illusory sense of agency from their alliance with the ruler?

Cooper offers a different interpretation. She argues that what looks like working-class support for Trump reflects significant changes in the composition of the working class itself. If we define working-class jobs as those that do not require a college degree, then “blue-collar” jobs (manufacturing, mining, and construction) represent a small subset of the total, since they employ many fewer people than low-wage service jobs: retail, sales, food service, home healthcare—jobs in which women are still disproportionately represented. In blue-collar industries, manufacturing has fallen as a share of employment while construction has remained fairly steady, though varying from year to year.

Although Trump won 50 percent of the votes cast by people who earn less than $50,000 a year (compared with Harris’s 48 percent), Cooper contends that what politicians and pundits are most concerned about when they talk about “working-class” support for Republicans is the political ideology and experience of a much narrower group of people: namely, those in older trades such as plumbing, electrical repairs, and trucking, who are often self-employed or small-business owners. Here, Cooper is drawing on work by the political scientists Vanessa Williamson and Theda Skocpol, who showed that a plurality of Tea Party supporters were self-employed small-business owners, often in real estate or construction or home repairs. (Few backers of the Tea Party were wage workers or public-sector workers, and despite their plebeian image, 41 percent were from the highest income quintile.) These voters transferred their support to Trump in 2016 and remained ardent backers throughout his first term. One-third of the January 6 Capitol rioters were small-business owners or self-employed people. Although in 2024, Trump won more votes from working-class people generally (measured in terms of income level or those without a college degree), the strongest supporters of the populist right, Cooper claims, are these aspiring entrepreneurs rather than people in the many other occupations that make up the modern working class: home health aides, retail clerks, delivery workers, hospital staff, and so on.

For these entrepreneurial types, the private titans and family-business owners with whom Trump has surrounded himself are models to emulate. The tax cuts that benefit the moguls appeal to them as well—whether as an aspirational goal or because small-business owners really do benefit from the same cuts, although not nearly to the same extent. Cooper recalls a 2017 rally at which Trump appeared in front of a sea of big rigs and a banner reading “Truckers for Tax Cuts.” (The tax cut then in question, which truckers would receive during Trump’s first term and which was just made permanent in the 2025 tax bill, was the “pass-through deduction,” which allows companies to pass income directly to their owners, who then pay income tax on it rather than the higher corporate tax while also taking a deduction on that business income.) In the political imaginary of the Trumpian right, the individual proprietor or the small family business has interests in common with the developers, landlords, builders, and hedge-fund billionaires in an alliance that, Cooper writes, joins “the smallest to the most grandiose of household production units.”

Cooper even ties abortion politics to the political economy, analyzing a remarkable line of thinking that blames abortion for the rise of the national debt. In 2022, the Republican members of the Congressional Joint Economic Committee issued a report professing to quantify the economic impact of abortion, making the case that its economic cost in 2019 was equal to “at least $6.9 trillion” (a figure derived from ludicrously abusing a methodology that assesses unrelated mortality risk), and that it also deprives Americans of valuable inventions and innovations, shrinks the labor force, and reduces funding for Social Security and Medicare.

This is a new twist on an old argument that linked “socialized medicine” to “welfare chiselers” who would “get ‘free abortions’ which you will pay for,” as Republican Congressman Robert Bauman put it in 1977. It also resonates with the admittedly extreme thought of the economist Gary North, who was an adherent of Christian Reconstructionism, an obscure sect founded in the 1960s that seeks the literal instantiation of Old Testament law in the civil sphere. North blamed the welfare state for eroding family bonds by making parents and children less economically dependent on each other. Universal prekindergarten means that parents are no longer the sole teachers of young children; Social Security means that adults no longer bear total responsibility for caring for their parents in old age. Shorn of these family commitments, citizens—according to North—will cease to be productive taxpayers and so stop generating the revenue that the welfare state needs to survive. Just as abortion cuts off new generations, the debt-fueled welfare state is actually “an agent of social, political, and economic bankruptcy.”

There is much that is speculative in Cooper’s book, and many places where the reader longs for more hard evidence. The chapter on abortion is one place where her approach feels overly schematic and in which her materialism seems to leave much unanswered, especially when it comes to political organizing. Doesn’t the growing importance of abortion in American politics have to do with the power of the evangelical right, or its alliance with Catholics who have long opposed the freedom to choose? Might not the pro-life movement be a grassroots social phenomenon with its own distinct norms, logic, and history—one that has to be understood on its own terms, not folded into the economic right?

Counterrevolution also provides a limited scope for those, left or right, who are interested in resisting the Trumpian right today. In the book’s closing pages, Cooper insists that the major political project for the left is to encourage Americans to see public finance as a liberatory tool, which means jettisoning the mindset of austerity. If only we could embrace an expansive political imagination and pursue “extravagant” social spending, as opposed to subsidies for private wealth combined with public austerity, we could lavish funds on such basics as universal healthcare and investments in higher education, public schools, and childcare. What political force would bring into being such a “fiscal and monetary revolution” is never spelled out. Cooper references a medley of disruptive tactics, such as “labor strikes, rent strikes, strategic defaults, urban riots, occupations of public space, and squatting”—but how to move from these diffuse protests to a broader change in the political imagination, let alone political power, goes unexamined.

Cooper’s own arguments suggest reasons for pessimism. Counterrevolution was written during the Biden years, when it seemed possible that Trumpism was in decline. That it surged back suggests how it may be rooted in broader structural changes in our economic order: the rise of a group of people who see themselves as unconstrained by older democratic norms, and whose conviction grows out of their absolute power in the workplace. Trump’s autocratic style is not just a quirk of his personality; it’s emblematic of the type of businessman he is.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Among other things, Trump is himself a product of the 1980s and the lasting changes that an earlier generation of conservative political leaders achieved. The hard anti-labor politics of Reagan changed what was permissible for the private sector, setting a new standard. Reagan fired more than 11,000 striking federal air-traffic controllers in 1981, barred them from the industry, and hired permanent replacements. His administration also emboldened private employers to fight their unions and hire strikebreakers. The result was a growing offensive against organized labor that contributed to the destruction of American unions (now just 6 percent of the private-sector workforce).

This offensive took its toll on American politics and, in particular, the base that once tended to vote for the Democrats. By creating an atomized and insecure working class no longer connected to powerful institutions that could foster a class identity, the assault on unions encouraged those harmed by the erosion of working-class power to look for their own answers; some of them would fall prey to the conspiratorial xenophobia of Trumpism.

Likewise, the undermining of large bureaucratic corporations that sought to draw on expertise and that were compelled, at least some of the time, to respond to public pressure or changing norms (for example, by proactively seeking to adapt to federal antidiscrimination laws, or by adopting measures of corporate success that incorporated environmental goals), and the emergence of privately held companies and funds that mostly did their business behind closed doors, only added to the sense of disempowerment and alienation experienced by working- and middle-class voters. Their economy was quite literally out of control—both their own control and that of many others, too.

Yet in this analysis of the loss of institutions and structures that can hold power accountable, one can find possible ways out of our bleak political present. Although Cooper does not fully develop this in Counterrevolution, her focus on ownership and economic structure offers us some hints about a path forward. To really take on Trumpism, liberals and the left will have to think less about restoring a tenuous normalcy by winning particular elections or countering the especially noxious parts of Trump’s agenda, and more about how to rebuild those economic and political institutions—unions, tenants’ organizations, independent media, political groups—that give people the experience of political power and collective action. Instead of answering Trump’s personalistic politics by telling voters to let competent experts back into the White House so that they can take control—let alone responding to Trump’s transphobia or anti-immigrant politics by adopting aspects of that language in an attempt to win back the people drawn to him—what we really need is a way to remind many middle- and working-class voters what it actually means to live in a society in which they exercise some measure of agency, and in which the leadership of that society is democratically accountable in a meaningful way.

No matter the fantasies of Trump and others, society is not divided up into fiefdoms of private enterprises and mini-autocracies run by a handful of rich men who are simply able to legislate reality as they want it to be. Rather, it is inherently interdependent and reciprocal. Those at the top might appear all-powerful, but they alone do not control the world. We might no longer have the economic structures and collective institutions of the past that helped manifest this basic truth in our everyday lives. But even in the mid-20th century, to the extent that large bureaucratic corporations became marginally more publicly accountable, it was only through organized political pressure, most centrally (though not only) from unions. And unions, in turn, have been able to play this democratizing role because they are institutions that tangibly express the idea that the economy is not a private domain or the extension of a single man’s will, but rather the creation of the daily labor of millions of people. (Local politics, too, can provide a beginning point for this kind of politics.)

This is a long-term undertaking, and its outcome is far from certain. But by giving us a vision of Trumpism that is grounded in material relationships and in the structure of our current economic order, Cooper offers us a way of thinking about how we might get from here to there: a hope that by pressing for changes that bring greater democracy to our material lives, we might eventually create a bigger challenge to the barbarism before us.

More from The Nation

After around 160 faculty members signed a resolution condemning the university, Cornell closed a disciplinary case against Dr. Eric Cheyfitz on the condition that he retires.

StudentNation

/

Gabe Levin

Arguably no American journalist wielded as much influence as Walter Lippmann did in the 20th century. But what did he do with that power?

Books & the Arts

/

Gerald Howard

Elon Musk’s car from space offered a vision for a sustainable and autonomous future. All along, it was as awkward, easily bruised, and volatile as the entrepreneur himself.

Feature

/

Maya Vinokour

As far back as 1958, Nation writers were grappling with the prospect of ‘artificial brains,’ particularly when placed in the hands of the military.

Column

/

Richard Kreitner

He has chosen to unleash a powerful and potentially cataclysmic new technology on the world with no regard for consequences.

Feature

/

Michael T. Klare