March 2026: Science history from 50, 100 and 150 years ago

A Greenland mystery; booming dunes

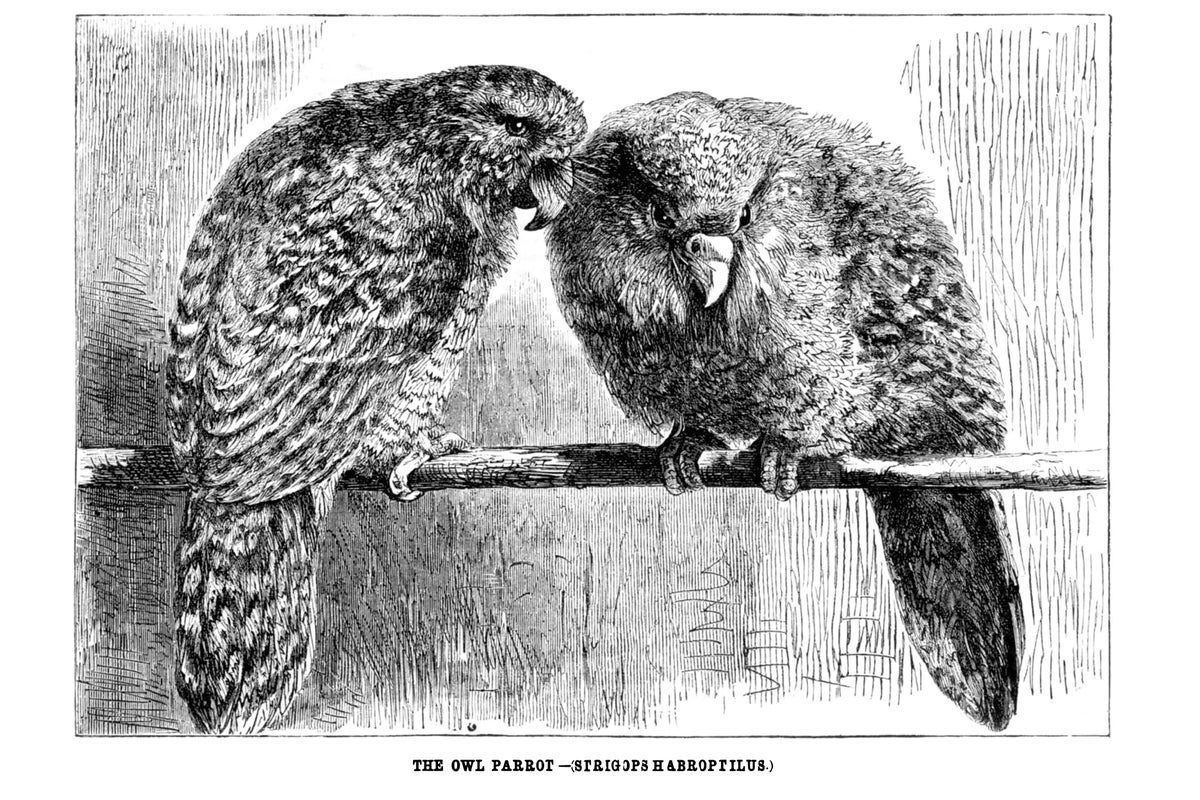

1876, The Owl Parrot: “This singular bird, sometimes called the night parrot, belongs to New Zealand. It has the form of a parrot but bears a facial aspect resembling that of an owl. But it is not a bird of prey, as it eats corn and nuts readily when in captivity. The specimens herewith illustrated are domiciled in the unrivaled collection in the gardens of the Royal Zoological Society in London, England.”

Scientific American, Vol. 34, No. 12; March 1876

1976

Catastrophe Theory

“Any object or concept can be represented as a form, a topological surface, and consequently any process can be regarded as a transition from one form to another. If the transition is smooth and continuous, there are well-established mathematical methods for describing it. In nature, however, the evolution of forms usually involves abrupt changes and perplexing divergences, or transformations. Because these transformations represent sudden disruptions of otherwise continuous processes, René Thom of the Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques in France termed them elementary catastrophes.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Such catastrophe theory has been particularly interesting in its applications to the biological and social sciences. Thom suggests applications in embryology, as well as in the theory of evolution, in reproduction, in the process of thought and in the generation of speech. For the living cell and for the organism, life is one catastrophe after another.”

Booming Dunes

“A sand dune would not seem to be a very likely candidate as a natural sound generator. But dunes in many parts of the world squeak, roar or boom. Acoustic sands have been described in desert legend but have received little scientific attention. Recently scientists have conducted the first quantitative analysis of the properties of an acoustic dune called Sand Mountain near Fallon, Nev. After trying several different methods, they found that the sand boomed loudest when a trench was rapidly dug in it with a flat-bladed shovel. The sound was like a short, low note on a cello; it lasted for less than two seconds and was readily audible at a distance of 30 meters. The booming could also be produced by pulling the sand downhill with the hand; in that case, strong vibrations reminiscent of a mild electric shock could be felt in the fingertips.”

1926

Greenland’s Norse Mystery

“The excavations carried out by Dr. Poul Nørlund of the National Museum, Copenhagen, at Herjolfsnes, the Old Norse settlement of Osterbygd, in Southern Greenland, throw light upon the mysterious fate of the early Norse settlers. In the ancient churchyard at Herjolfsnes, some 200 valuable relics were found, including coffins, skeletons of the old Vikings in their shrouds, well-preserved garments, implements, tools, ornaments and Christian crosses.

The style and cut of many of the costumes show that the Norsemen were in communication with Europe up to then; however, evidence shows around that time a fatal change of climate occurred in these northern latitudes. Whereas Herjolfsnes had been free of ice all through the summer, it suddenly became blocked virtually all through the year. Being cut off from Europe and being called upon to face a hard climate, the colonists gradually deteriorated in physique. This is evidenced by an examination of the skeletons. Against the Eskimos, so brilliantly adapted to the arctic conditions, the physically weakened Norsemen could not hold out, and their doom was sealed by the encroaching Greenland ice.”

The Carolina Wren

“The early naturalists in America were woefully twisted in the matter of names. Not only were absurd appellations used in imitation of Old World names—such as robin, partridge and pheasant—but also terms to suggest restricted habitats. Thus, for widely distributed species, we have such titles as Maryland yellow-throat, Louisiana heron and Carolina wren. The Carolinas have no more right to be honored with the name of this little songster than have any other states in its range. If I were to pick a favorite bird, one of truly heroic mold and one that is worthy of the greatest admiration for its abilities as a musician, architect, artisan, its happy, optimistic disposition and its domestic virtues, I would choose the Carolina wren.”

1876

Another Obnoxious Postal Law

“An obnoxious postal law was passed during the closing hours of the last congressional session, the effect of which was to double the postage on transient newspapers, magazines and periodicals, books, and merchandise. A new bill stipulates the following: For distances up to 300 miles, one cent for each two ounces; for distances between 300 and 800 miles, two cents; between 800 and 1,500 miles, three cents, and so forth.

The proposed measure will bring chaos on postal affairs. It presupposes a geographical knowledge throughout the entire population, which never could exist. Not only must a man know the distance of every post office from his residence, but the distance of every post office from every other post office, else he could not stamp his packages correctly. Congress should not pass this bill.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.