Robot libraries filled with tiny glass ‘books’ could store data for millennia

A Microsoft Research study suggests glass blocks etched with lasers could provide enduring data archives

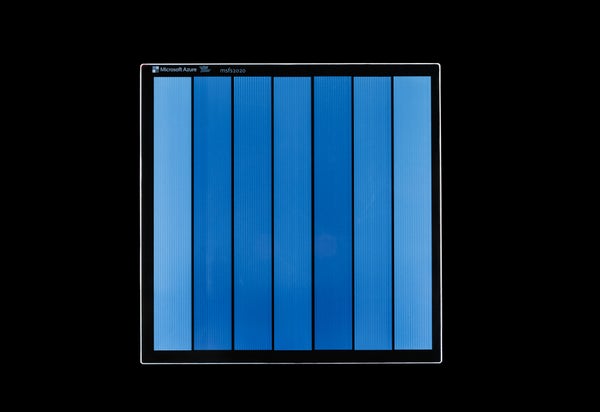

A piece of glass with a copy of Microsoft Flight Simulator map data encoded on it.

A team at Microsoft Research combined lasers, machine learning and tiny glass rectangles to demonstrate a new robotic data storage system that could, in theory, still be readable 10,000 years from now—twice as long as humans have been writing things down to date. The process, described recently in Nature, is designed for archiving records that don’t need to be accessed often, such as certain climate measurements, historical records and other reference materials. If scaled, the technology could someday store mountains of humanity’s accumulated knowledge in libraries made of glass.

“This is an exciting and very promising development,” says Doris Möncke, a glass chemist and an associate professor for glass science at Alfred University in New York State, who wasn’t involved in the study. “They sure went farther than anything I have seen recently at glass conferences.”

The new system can write, read and store 4.8 terabytes of data in a minuscule piece of glass with a surface of 12 centimeters squared and a thickness of two millimeters. It crams that much information into such a small space by etching 301 layers of three-dimensional pixel-like holes called voxels stacked on top of one another. To record information, a laser zaps data into precise depths of the glass using a series of energy pulses that each last for about one quadrillionth of a second. Filling the glass “book” with data requires 48.9 kilojoules of energy, or about the calories contained in half a brussels sprout. Because the data are stacked, reading a single layer is a bit complex; a microscope focuses on each layer in the glass, and the resulting images are processed with machine learning to determine matching symbols.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

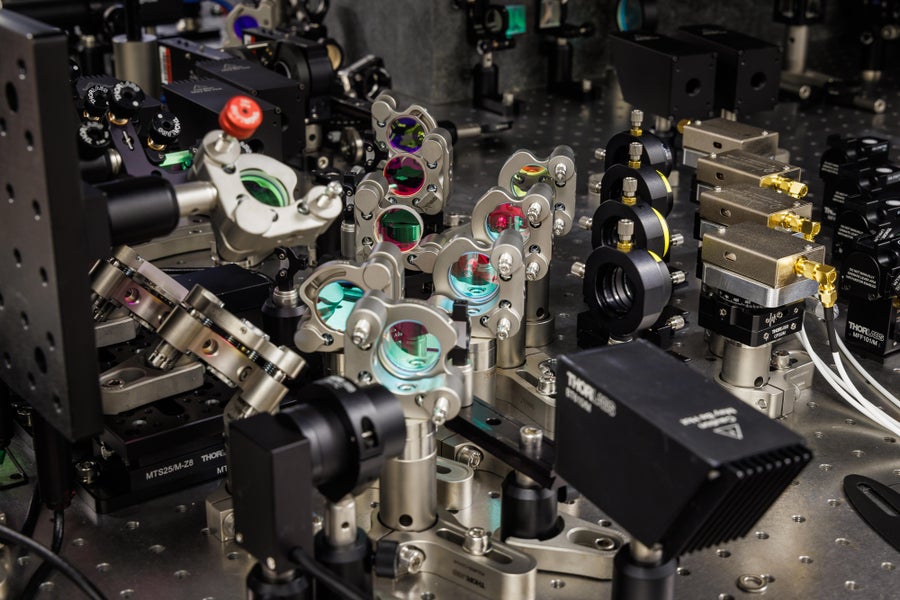

Closeup of equipment that allows researchers to encode data on small pieces of glass.

Data systems can introduce errors when they are reading or writing or even during storage, so some of the glass book’s storage space is dedicated to error correction. The researchers tested how much extra space was needed to reliably read and write a sector in the glass and determined that different locations required varying levels of redundancy.

To figure out how long data stored in the glass might be readable, the team heated it in a furnace at increasing temperatures up to 500 degrees Celsius and then measured how light passed through the glass to see how it had changed. Extrapolating the data indicated the glass books would remain stable at 290 degrees C for more than 10,000 years—and even longer at room temperature.

Möncke expects the new glass to have “high longevity” as long as it isn’t melted, broken or “forgotten in a damp basement.” She had previously studied radiation damage to glass, and that glass showed changes in structure 10 to 20 years after the damage occurred. But the defects weren’t cavities like those etched to record data. “I believe those cavities are indeed long-term stable,” Möncke says, because the laser writing process causes more permanent changes to the Microsoft Research team’s glass. And because the cavities are contained within the glass rather than exposed to the outside world, they’re less likely to cause cracks, she adds, though “it’s certainly worth a long-time study!”

The new research did not account for mechanical stress or corrosion as part of longevity testing, and both are likely to affect the readability of the data over a long time. Also, for the data to be readable across centuries, every single person or robot who ever handles the glass must avoid accidentally losing it or mistaking it for part of a futuristic domino set.

Regardless, the technology could be a big improvement over current archival storage systems, such as hard drives, which may last a decade or two before they need to be replaced. DNA that can be used as a dense, efficient archive is also under development, although it’s much more challenging to extract the data from that medium.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.