The laser-based method uses one laser flash to make sensors that check temperature on hot or cold surfaces without adding extra layers or steps.

A team led by Prof. Kaichen Xu, Prof. Haibo Xie, and collaborators at Zhejiang University has developed a laser-based method for making thin-film temperature sensors that work across a temperature range from –50 °C to 950 °C, without using protective coatings.

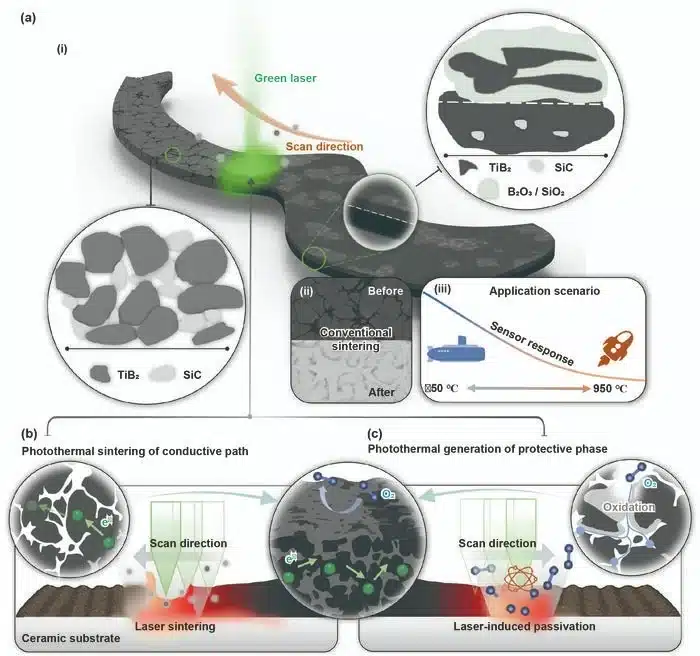

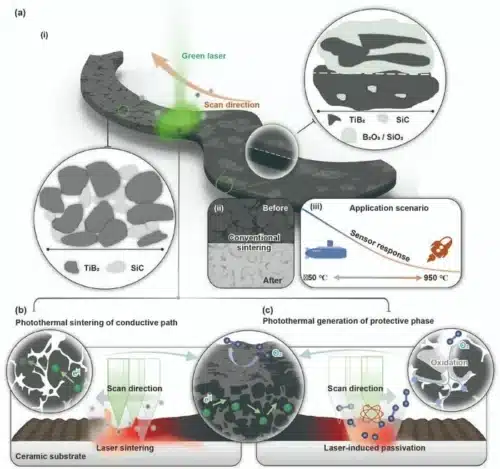

This method uses a single laser pulse to do two things: it creates a temperature-sensing layer and forms a glass-like surface layer. When the laser hits the material, it heats it, causing crystallization. This allows the material to conduct electricity and respond to changes in temperature. At the same time, the surface forms a layer that resists oxidation.

The team built this method as part of their work on electronics that can be shaped and placed on different surfaces. These thin-film sensors are made to work on surfaces that face high heat, such as parts in engines, energy systems, and vehicle components.

Older methods for making temperature sensors involve many steps: adding several layers, long heating processes, and putting on extra coatings to protect the sensor. These steps take time, need control, and use more materials. The new laser method brings all this into one step.

Because the laser creates both layers at once, it removes the need for coating materials and shortens the process. It also makes it easier to apply sensors on curved or uneven surfaces, such as housings or pipelines. No adhesives or transfer steps are needed.

This process uses fewer materials, saves energy, and lowers the chance of sensor failure during production. It allows fast and direct use of sensors on the parts being checked.

The result is a sensor that gives real-time temperature readings with stable performance. In lab tests, the sensors showed 1.2% signal drift after running at high temperatures for 20 hours.

This can help engineers find signs of heat or stress in machines, allowing early repairs and avoiding breakdowns. Because the method is fast, simple, and works over a wide temperature range, it could make sensing more usable in many places.

The team is now working to use this method for sensors that measure pressure, strain, and heat flow, with the goal of building systems that work in settings like factories and space.