Rules of mysterious ancient Roman board game decoded by AI

A Roman stone board game has been unplayable since its discovery more than a century ago, but AI might have just worked out the rules

The possible gameboard with pencil marks highlighting the incised lines.

It was the summer of 2020, and researcher Walter Crist was wandering around the exhibits inside a Dutch museum dedicated to the presence of the ancient Roman empire in the Netherlands. As a scientist who studies ancient board games, one exhibit stuck out to Crist: a stone game board dating to the late Roman Empire. It was about eight inches across and etched with angular lines that roughly formed the shape of an oblong octagon inside a rectangle.

“I thought to myself, ‘Well, that’s very interesting,’ because the pattern on it—it’s not something I had ever seen in the literature before,” Crist says.

What the game was called and how it was played were a mystery, too.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Crist contacted the museum curators to get a closer look. And now he and his colleagues believe they’ve decoded the game in a first-of-its-kind study using a combination of more traditional archaeological methods and artificial intelligence. According to the analysis, the object appears to be a sort of “blocking game.” In these types of games, one player tries to block another from moving; one example is tic-tac-toe.

The research was published on Monday in the journal Antiquity.

Crist, now a guest lecturer at Leiden University in the Netherlands, recalls that when he and his team started investigating the board game, they didn’t have a ton of details to work with. They knew that the game board had been found around the late 1800s or early 1900s in the southeastern Netherlands’ city of Heerlen—which would have been the city of Coriovallum in Roman times. The board was made out limestone that was imported from France. And the game was likely played casually and may not have been particularly notable, in part because there is no known documentation of it in written texts from the time.

Excavation of two pottery kilns in Heerlen, 1940.

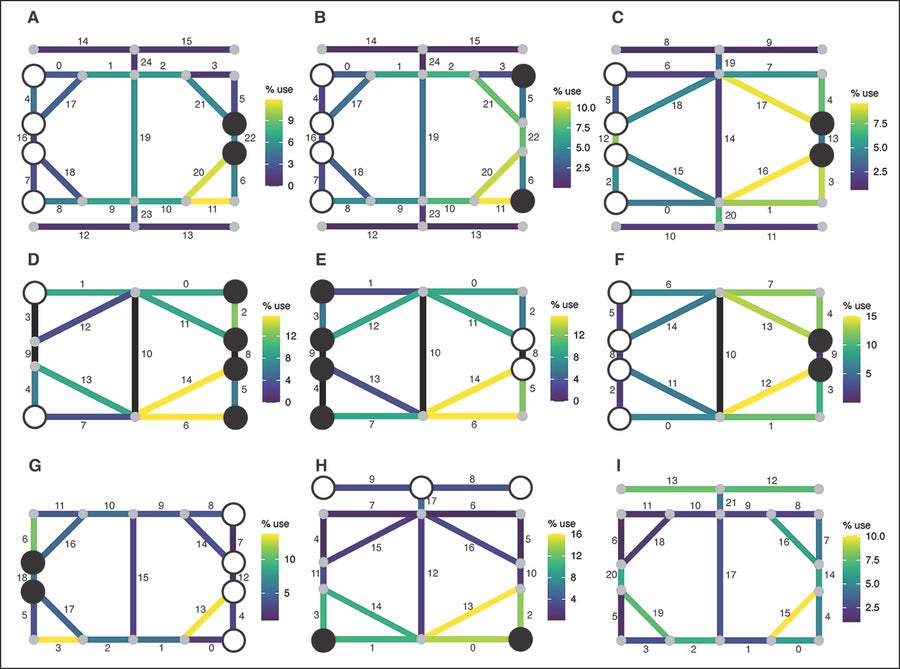

To decipher the rules, Crist’s team programmed two AI agents to play the game over and over again using more than 100 different sets of rules taken from other known European games, both ancient and modern. As the AI agents played—1,000 games per set of rules—the researchers tracked how the pieces moved. Then they compared the moves with the levels of wear on areas of the board, tracing which gameplay seemed to replicate grooves on the stone.

The team found nine rule sets that appeared “consistent” with the wear on the board. “And they were all variations of this same kind of blocking game,” Crist says.

This type of game was played in the 19th and 20th centuries in Scandinavia, and researchers thought it dated to early medieval times. But the Roman game is the earliest example of such a game in Europe, Crist says. He and his team called the game Ludus Coriovalli, Latin for “the game from Coriovallum.” (You can play it online here.)

Results of the AI simulation showing nine possible game boards. In these games, the player with more pieces attempts to block the player with fewer pieces.

Crist hopes the study will help researchers solve other ancient board games. Such games offer a way to connect the ancient past to our own lives, he says. Indeed, they haven’t changed much over the centuries. The ancient Egyptian board game Senet, for example, might not have been all that different from Sorry! Chess, meanwhile, is thought to have originated in ancient India, and nobody really knows when or where backgammon originated.

Understanding how ancient games might’ve been played, Crist says, “can lead us to new insights on how people in the past enjoyed their lives.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.