America’s working and middle classes face a dual crisis: declining trust that government can deliver for ordinary people, and an accelerating concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few. Yet, rather than train their focus outwards, Democrats appear trapped in an increasingly bitter internal fight about the direction of the party—one centered around the two broad concepts of “populism” and “abundance.”

Populists, represented by figures like Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, argue that America’s defining problem is an inequality so extreme that three billionaires hold more wealth than the bottom half of the population combined. For them, the villains are clear: unchecked corporate power, entrenched oligarchy, and rampant inequality.

On the other side is the rising “abundance” framework popularized by journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson and quickly gaining influence among centrist Democrats. Here, the primary obstacle isn’t inequality per se but the paralyzing inability of government to deliver tangible outcomes, particularly in blue cities and states: affordable housing, renewable energy, public transit, and infrastructure at scale. Abundance advocates see Democratic policymaking itself—its layers of bureaucracy, endless veto points pushed on by advocacy groups, and entrenched NIMBYism—as the main culprit.

While populism is a compelling message and diagnosis, it alone isn’t sufficient. Populist rhetoric frequently underestimates or sidesteps critical governance problems: bureaucratic complexity, policy entrenchment, and inefficient public administration. These challenges aren’t purely driven by corporate elites—they’re embedded features of governance itself, demanding their own targeted solutions beyond populist critiques alone.

Both perspectives offer genuine insight, and there’s no inherent reason their best ideas can’t be integrated into a unified vision—call it “populist abundance.” But rather than engage in constructive synthesis, Democrats have become trapped in factional trench warfare. Beneath the surface, this conflict isn’t simply about competing policy preferences; it’s also driven by powerful donors and party insiders explicitly hostile to the populist left, who see the abundance framework as a convenient vehicle to marginalize critiques of corporate power.

The recurring friction between centrist and progressive Democrats often gets framed as a clash of personalities or ideology. But beneath that lies a more durable structural imbalance: the progressive, populist wing of the party—rooted in the Sanders campaigns—remains stuck in the position of junior partner. It has ideas, energy, and a sizable base. What it doesn’t have is institutional leverage: few governorships, no major cities, and limited legislative leadership. As a result, progressives are routinely blamed for decisions they didn’t make and outcomes they couldn’t control. The 2024 loss is the most recent example. Kamala Harris and Joe Biden ran on a strategy and platform crafted by centrists, not the populist left. Yet when they lost, it was the progressives—again—who were accused of undermining the party. As David Dayen put it: “Nobody has ever had more money to implement their theory of politics than David Shor in 2024. He failed miserably.” And yet, somehow, it’s still the populist left that’s asked to step back.

Centrist Democrats, backed by donors and embedded in institutions, default to caution and consensus—what gets called “pragmatism” in Washington but often just means avoiding conflict with powerful interests. Progressives, meanwhile, push for a synthesis: pairing economic populism with a commitment to competent, expansive governance. But without real institutional weight, that synthesis remains more aspiration than reality. If the populist wing wants to stop being the scapegoat every time the center fails, it needs to focus not just on policy or protest—but on building durable power inside the party.

In short, Democrats are stuck not because they’re philosophically confused but because factional interests and structural inequalities block a necessary synthesis. To achieve meaningful change, the party must reject false binaries between confronting corporate power and improving state capacity, and instead must pursue both simultaneously. Recognizing this factional dynamic—and the institutional obstacles that perpetuate it—is the first step toward effectively integrating populism and abundance.

The debate about which of these directions Democrats should embrace has turned increasingly acrimonious. Abundance proponent Jonathan Chait, for example, frames the tension within liberalism not merely as a polite ideological dispute but as a critical and clarifying factional “civil war” over control and direction of the Democratic Party itself. Far from viewing this conflict as destructive, Chait regards it as necessary and productive—a way to resolve a long-standing stalemate and offer voters an alternative to what he sees as progressive politics’ procedural paralysis and ideological rigidity.

Meanwhile, a growing chorus on the left has voiced skepticism about abundance—less about the abstract goal of increasing state capacity and more about its conspicuous ambivalence toward oligarchy and corporate power. Aaron Regunberg has articulated this concern sharply, noting the troubling web of donors underwriting abundance advocacy. Figures like Reid Hoffman, Michael Bloomberg, and heirs to corporate fortunes aren’t neutral observers—they actively fund efforts that seek to marginalize antitrust reformers, labor advocates, and redistributionist policies associated with Sanders, Warren, and Lina Khan.

Consider WelcomeFest, the so-called “Abundance Coachella” quietly bankrolled by private equity titans and billionaire donors—an event that vividly highlights the contradiction between abundance’s professed neutrality and its underlying ideological and factional character. If the abundance movement is truly committed to its stated goals, it cannot dismiss criticisms of its elite backers as conspiratorial distractions or credibly claim neutrality while relying on financiers whose primary goal is to blunt redistributive politics. A genuinely credible abundance strategy must openly confront and challenge anti-populist donor influence to ensure that it serves the public, not elite capture.

While abundance advocates claim a pure focus on effective governance, it’s impossible to ignore the anti-populist donors aligning with this agenda. Addressing this influence directly doesn’t dismiss the necessity of government efficiency, but it clarifies that any credible abundance strategy must confront elite influence wherever it undermines accountability—irrespective of factional allegiances. The debate about donors isn’t a distraction; it’s central to ensuring policy outcomes serve public rather than private interests.

Meanwhile, populists are often criticized for lacking a clear and practical “theory of power”—a concrete plan to realistically overcome entrenched opposition and institutional inertia. This critique is valid. For populist abundance to succeed, populists must move beyond moral clarity alone and explicitly articulate how they plan to confront, neutralize, or win over skeptics and adversaries without sacrificing core progressive commitments.

A recent exchange between Ezra Klein and Majority Report host Sam Seder vividly captures the heart of this tension. Klein effectively highlights that procedural complexity—rather than outright corporate malice—frequently stalls critical projects in liberal cities. Yet he underestimates how wealthy homeowners and influential developers actively exploit this complexity to protect their interests. Conversely, Seder persuasively argues that seemingly neutral bureaucracy often conceals deeper structural inequalities, though left-populist critiques like his typically lack detailed, practical strategies to overcome these entrenched barriers.

Both Klein and Seder offer compelling insights, but each tends to remain anchored within his own analytical frame, frequently talking past each other. This intraparty dynamic represents a missed opportunity to synthesize the insights of each perspective. Rather than seeing potential allies, each faction—including my own—has increasingly perceived the other as a threat, driven in part by competing donors, activist networks, and internal rivalries. Further complicating matters, abundance advocates—often aligned with Silicon Valley and Effective Altruism circles—imply that corporate interests and policymakers can resolve their differences amicably, through something resembling a gentleman’s handshake. Populists, deeply skeptical of this premise, insist that meaningful change demands explicit confrontation with corporate power. Ultimately, this disconnect highlights the urgent need for Democratic factions to recognize and bridge their fundamentally different ideological starting points, blending coalition-building and pragmatic governance reforms with a clear-eyed willingness to challenge entrenched economic interests directly.

These debates often obscure rather than clarify what each camp actually wants. But when clearly defined, the goals of abundance, social democracy, and populist anti-monopoly politics are more complementary than contradictory.

An abundance framework emphasizes removing procedural obstacles that block the delivery of public goods—affordable housing, public transit, renewable energy—particularly in blue regions with entrenched local resistance. Social democracy, by contrast, goes deeper: it’s not just about improving markets, but taking vital goods like healthcare, education, and housing out of market logic entirely, ensuring universal provision and aiming for full employment. Meanwhile, anti-monopoly populism, as championed by Elizabeth Warren and Lina Khan, targets concentrated corporate power directly, seeking to democratize economic decision-making and prevent elite capture of government.

These approaches can reinforce one another: abundance can streamline the capacity needed to implement social democracy’s expansive guarantees. Populism ensures that abundance doesn’t slide into technocratic subsidies for corporate power. And social democracy gives abundance a moral compass, grounding its reforms in universalism and fairness. But there are tensions too. Abundance may worry that social democracy reinstates paralyzing bureaucracy; social democrats may fear abundance tips too far toward market logic; and populists argue that unless power is confronted, both will fall short.

Take, for instance, a scenario from local governance: In pursuit of environmental justice, a city council mandates the creation of new advisory boards, numerous drafts and revisions of sustainability plans, and multiple layers of administrative review. Individually, each step seems well-intentioned, aimed at transparency and accountability. But collectively, these layers of oversight become burdensome and counterproductive. Public servants spend more energy navigating procedural mazes than delivering tangible outcomes, inadvertently creating new choke points that interest groups leverage to obstruct meaningful action.

Abundance advocates are right to diagnose the institutional sclerosis that results when governance becomes a patchwork of individually negotiated deals. But streamlining alone won’t solve the problem. Procedural complexity isn’t just inefficient—it’s often a tool used by powerful interests to block redistribution and reinforce the status quo. A governing strategy that actually builds legitimacy must do both: cut through the bureaucratic fog and confront the entrenched economic power that shapes it. That means pairing an abundance agenda focused on delivery and capacity with a populist commitment to equity, redistribution, and democratic control. Without that integration, reform efforts risk becoming either toothless or captured.

While Klein and Thompson and other abundance advocates often attempt to present their arguments as purely policy-driven, divorced from ideological or political motivations, this framing is somewhat disingenuous of the political life of abundance beyond their book. At times, the rhetoric at WelcomeFest made it seem like the biggest obstacles weren’t landlords or developers but the few Democrats still talking about corporate power. The insistence that abundance is about neutral technocratic solutions rather than factional politics obscures a very real ideological battle underway for influence within the Democratic Party—a battle backed by powerful corporate donors and strategic political calculations.

Jeff Hauser, writing in The American Prospect, argues that the centrist obsession with “popularism” and “abundance” didn’t merely fall short—it contributed directly to Democrats’ 2024 defeat. At events like WelcomeFest, the party leaned into a strategy of avoiding controversy, chasing the median voter through polling, and stripping away ideological clarity. The result: candidates with no compelling message, and even less capacity to inspire. Despite massive investments in data, ads, and message discipline—funded by billionaires like Bill Gates and Reid Hoffman—voters sensed that the party stood for little. Hauser’s warning is pointed: Technocracy without values doesn’t build public confidence; it drains it. And in prioritizing elite consensus over grassroots engagement, Democrats risk losing not just elections but even their reason for existing.

This factional tension surfaced clearly in a recent poll from Demand Progress, where 59 percent of Democratic voters preferred explicit populist appeals confronting corporate power, compared to just 17 percent favoring abundance-style messaging focused on governance reforms. Populists seized on the poll, while abundance proponents dismissed it as flawed. This confusion partly arises because abundance originally targeted problems specific to blue cities and states—issues like housing shortages and infrastructure delays—raising doubts about its suitability as an electoral message in purple or swing districts. Lost in this polarization is the obvious opportunity: harnessing populism’s electoral resonance to win power, while leveraging abundance’s insights to govern effectively.

History suggests the most impactful progressive movements never saw these impulses as mutually exclusive. Instead, landmark moments of transformative change—the New Deal, the civil rights era, and postwar social democracies—succeeded precisely because they blended sharp populist critiques of concentrated economic power with practical reforms to enhance state capacity and institutional effectiveness. Their achievements hinged on opting instead for a synthesis that recognized confronting corporate oligarchy and improving governmental performance as interdependent tasks. This integrated approach offers a critical lesson for contemporary Democrats—one they urgently need to revisit today.

James Kloppenberg, in Uncertain Victory, traces precisely this tension within early-20th-century Progressivism. Populist reformers like Louis Brandeis argued that unchecked corporate monopolies posed existential threats to American democracy, necessitating aggressive antitrust enforcement and rigorous democratic oversight. In contrast, technocratic progressives such as Herbert Croly and Walter Lippmann envisioned more streamlined and scientifically managed governance as a way to achieve public benefits without directly disrupting capitalist structures. Kloppenberg illustrates how these conflicting impulses nevertheless found common ground at critical moments, producing landmark syntheses like the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission—cases where democratic accountability and administrative effectiveness reinforced each other to produce lasting structural change.

The New Dealers, led by Franklin Roosevelt and Frances Perkins, forged a uniquely American blend, connecting populist demands to constrain corporate power with a commitment to building an effective, activist federal government. Faced with the existential threat of the Great Depression, Roosevelt positioned the state as not merely a temporary economic caretaker but a permanent guarantor of democracy and social stability. Key advisers like economist Rexford Tugwell and legal theorist Adolf Berle Jr. shaped the intellectual core of this vision—Tugwell pushing ambitious federal planning to correct economic imbalances, and Berle proposing a legal restructuring of capitalism itself, empowering government oversight to curb corporate abuses. Perkins, Roosevelt’s transformative labor secretary, operationalized these ideas through concrete policies—Social Security, unemployment insurance, and minimum wage laws—that didn’t just redistribute wealth but institutionalized a robust welfare state.

The New Dealers built a lasting administrative infrastructure—such as the National Labor Relations Board and Securities and Exchange Commission—fusing populist urgency with bureaucratic efficiency. The result was a structural redefinition of government’s relationship to markets and citizens, demonstrating that populist challenges to economic power and an expansion of state capacity need not be at odds but could mutually reinforce each other—a nuanced legacy particularly instructive for contemporary Democratic debates.

John Maynard Keynes similarly rejected the false choice between populism and abundance. Zachary Carter’s The Price of Peace shows that Keynes viewed prosperity as meaningless if not widely shared and democratically accountable. While populism’s critiques of inequality resonated deeply with him, Keynes argued explicitly for expanding state capacity to direct investment and manage capitalist dynamism. His goal was not socialist central planning but what he called “the comprehensive socialization of investment”—curbing the unchecked economic power of investors (the “rentiers”) while bolstering the government’s ability to channel private capital toward broadly beneficial ends. Keynes saw clearly that confronting inequality and increasing governmental efficiency were interdependent goals, essential for sustained prosperity and democratic stability.

Postwar European social democracy—analyzed by Adam Przeworski in Capitalism and Social Democracy—provides yet another successful example of melding these priorities. Rejecting revolutionary socialism, European social democrats strategically embraced capitalism’s productive potential while insisting on governmental responsibility to redistribute benefits equitably. Social-democratic parties confronted corporate power by empowering unions, creating robust public health and education systems, and investing heavily in infrastructure, thereby redistributing wealth downward. Crucially, these parties also prioritized building effective, professionalized bureaucracies capable of delivering social welfare.

Nelson Lichtenstein’s biography of Walter Reuther, The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit, illustrates how the combination of populist critique and supply-side abundance was realized through a distinctly American form of postwar social democracy: industrial democracy. Reuther, the leader of the United Auto Workers, tied enhanced industrial production and technological innovation to the democratic redistribution of economic power directly into workers’ hands. He championed an ambitious vision of workers actively participating in industrial governance, including making decisions on investments, productivity standards, and workplace conditions. This exemplified his belief that robust economic growth and a vibrant democracy depended fundamentally on worker empowerment within industrial structures. Through this framework, Reuther’s agenda of universal healthcare, public housing, extensive infrastructure investment, and full employment was not merely about economic fairness—it was about creating the institutional architecture for lasting industrial democracy, embodying America’s own pragmatic fusion of social democracy.

Similarly, the civil rights movement’s pursuit of economic justice, led by figures like A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King Jr., fundamentally shaped Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. Johnson’s expansive agenda recognized racial equality as inseparable from economic redistribution and effective government action. Beyond the Civil Rights Act, Voting Rights Act, and Fair Housing Act—which dismantled legal barriers to racial equality—Johnson enacted transformative economic measures such as Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, robust education funding, and major federal investments in housing. Randolph and Rustin’s ambitious “Freedom Budget” pushed even further, advocating aggressive federal programs aimed at achieving full employment, unionization, higher wages, and wealth redistribution. They framed confronting corporate power as complementary, not contradictory, to efficient and expansive governmental institutions capable of delivering these material gains effectively.

Contemporary Democrats can similarly transcend factional polarization by recognizing that genuinely effective progressive politics requires both confrontation with corporate oligarchy and robust governmental capacity to deliver tangible benefits. A synthesis modeled on historical successes—grounded in confronting corporate power while improving state capacity—offers a viable and necessary path forward.

Progressive skepticism of the contemporary abundance framework often stems from how closely it appears to echo the Atari Democrats and neoliberals of the 1980s. But the abundance coalition fundamentally diverges from the Atari Democrats on key ideological grounds. While today’s abundance advocates similarly highlight efficient governance, market-oriented reforms, and streamlined regulatory frameworks, their agenda isn’t merely a neoliberal revival: its proponents clearly frame their project as restoring robust state capacity, expansive public infrastructure investment, and effective governance—rather than deregulation or corporate dominance alone.

While the Atari Democrats distanced themselves from New Deal–era labor protections and Keynesian social spending, courting suburban professionals and embracing deregulation, many of today’s abundance proponents draw directly from a New Deal–inspired vision of active government, especially through ambitious public investments in infrastructure and industrial policy.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Yet this encouraging side of the abundance vision remains vulnerable to legitimate skepticism, given some of the prominent people floating around the movement. High-profile figures such as Josh Barro and Matt Yglesias often articulate the abundance agenda through critiques of organized labor, regulatory frameworks, and pretty much any social justice organization raising valid concerns about whether this faction can truly commit to economic justice and social democracy. If the movement’s public face frequently appears hostile to redistribution and labor, progressive critics understandably question whether abundance advocates will genuinely deliver the balanced and equitable governance they promise. To succeed politically and substantively, abundance’s progressive wing must convincingly differentiate itself from voices whose primary commitments undermine broader goals of equity and redistribution. If the abundance coalition cannot distance itself from the billionaire class underwriting it—and the anti-populist impulses that come with it—it risks becoming not a governing vision but a technocratic buffer to prevent more transformative reforms.

Programs like California’s Transformative Climate Communities (TCC) provide a compelling template for blending populist redistribution with abundance-oriented state capacity. By placing historically marginalized communities directly in control, TCC ensures that substantial public investments—affordable housing, renewable energy, urban greening—translate into both effective policy outcomes and genuine economic empowerment. As Alvaro Sanchez emphasizes, TCC’s success derives from coupling expanded governmental resources with democratic accountability and targeted equity, demonstrating that populist critiques and abundance-driven efficiency can, indeed, reinforce each other.

Economist Mariana Mazzucato also offers a way out of the stale binary between populism and abundance by reframing what government is for. Her core argument is simple but radical: the state isn’t just a referee or safety net—it’s a builder, a shaper of markets, a driver of innovation. From the internet to vaccines, public institutions have long made the foundational investments that private industry builds on. But we rarely treat government that way. Instead, we underfund it, strip it of ambition, and ask it only to clean up messes. Mazzucato flips that script. She argues for a mission-driven state—one that sets clear goals like decarbonization or universal care, directs capital accordingly, and ensures public investments yield public returns. In doing so, she synthesizes populism’s demand to confront corporate power with abundance’s call for effective governance. Her version of abundance isn’t technocratic—it’s democratic. It’s not about doing more with less. It’s about using state power to do big things well—and making sure the benefits don’t flow upward.

Franklin Roosevelt saw clearly what many Democrats today miss: that abundance and populism were never opposites but mutually reinforcing elements of a robust democracy. In 1938, Roosevelt powerfully articulated this fusion, warning Americans against the dual threats of economic oligarchy and fascism:

The liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself…Among us today a concentration of private power without equal in history is growing.

This concentration is seriously impairing the economic effectiveness of private enterprise as a way of providing employment for labor and capital and as a way of assuring a more equitable distribution of income and earnings among the people of the nation as a whole.

We believe in a way of living in which political democracy and free private enterprise for profit should serve and protect each other—to ensure a maximum of human liberty not for a few but for all.… No people, least of all a people with our traditions of personal liberty, will endure the slow erosion of opportunity for the common man, the oppressive sense of helplessness under the domination of a few, which are overshadowing our whole economic life.

Roosevelt’s insight—that concentrated economic power corrodes democracy, while democratic governance must deliver results—remains the clearest antidote to today’s sterile debate between Bernie’s populism and Klein and Thompson’s abundance.

Populism without power is theater. Technocracy without redistribution is surrender. One diagnoses the crisis. The other builds tools no one can access. Neither changes outcomes. It’s like a doctor declaring what’s killing you—then walking out of the room. Or a hospital in a neighborhood where no one can afford to walk through the door. One names the rot. The other papers over it. Real governing means doing both: naming the forces gutting democracy and having the power to stop them. Without that, Democrats aren’t solving the problem. They’re managing the decline.

More from The Nation

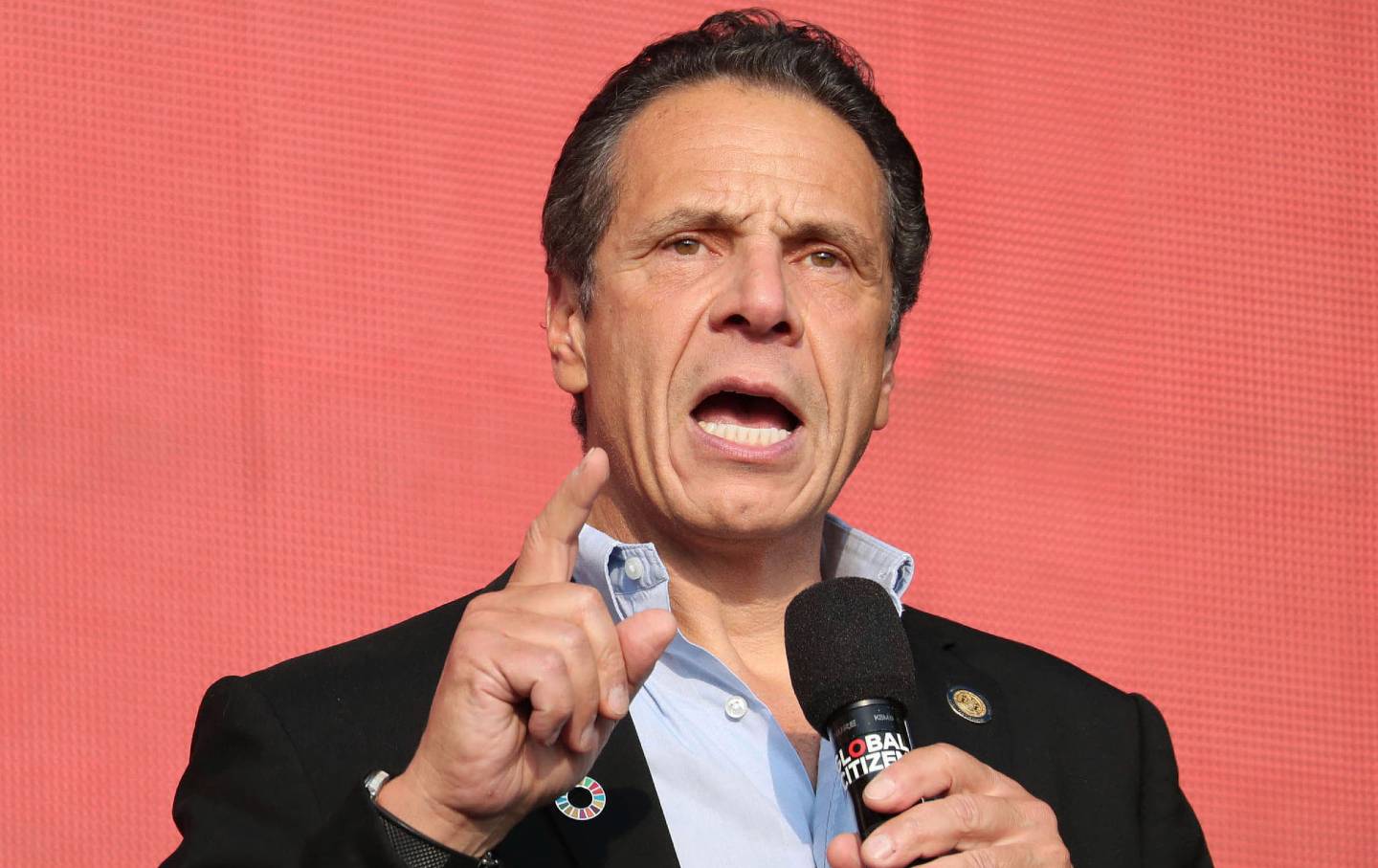

Cuomo claims that “housing is a top priority.” A dig into his track record says something very different.

Tracy Rosenthal

A mural in Oaxaca honoring the disappeared women.

OppArt

/

URTARTE

After law enforcement assaulted Senator Alex Padilla, we know: We are the only guardrails. Show up at a “No Kings” rally Saturday.

Joan Walsh

Americans have a right to assemble and a right to petition for the redress of grievances. They will use those rights this weekend to resist Trumpism.

John Nichols