Game developers didn’t have it easy in the 1990s. Because they had extremely limited computing power, they had to write their code as efficiently as possible. Consider the first-person shooter Quake III Arena, usually called Quake 3, for example: players navigated a three-dimensional world, so the programmers had to find the cleverest ways to handle 3D graphics and the associated calculations.

Quake 3 released in 1999 and is considered one of the best computer games of its time. It had a lasting impact on the industry. This legacy wasn’t so much due to the story, but rather because Quake 3 was one of the first multiplayer first-person shooters. Players could connect their computers via network cables or the internet to compete in real time.

The game’s code left a mark too. It included an extremely efficient algorithm that still amazes experts and sparks curiosity among scientists.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A strange code

To figure out the orientations of objects, characters or other players in three-dimensional space mathematically, you create a vector, which is essentially an arrow that shows direction. To compare vectors, they need to be normalized to the same length, so you have to scale them accordingly. And that’s where a tricky calculation comes up: the inverse square root, which is one divided by the square root of a number.

If I asked you to calculate the inverse square root of 26 without a calculator, you’d probably be stuck for a while—and honestly, so would I. Back in the 1990s computers faced the same challenge. Although they could crunch the numbers, the process demanded a lot of processing power—which can mean the calculation takes a lot of time. One problem was the square root itself; another was the division. That’s why the Quake 3 programmers hunted for a better way to find this inverse square root. And indeed, their source code revealed an ingenious solution.

What’s fascinating is that the developers never advertised their trick. If Quake 3’s source code hadn’t gone open source, their method might have stayed hidden forever. But once it was released, curious enthusiasts took notice. When they discovered the code snippet for calculating the inverse square root, they were baffled—it was difficult to follow, and the developers’ accompanying comments weren’t particularly helpful. But gradually people figured out how the code worked.

Today there are many tutorials that guide you step-by-step through the program code. These walkthroughs exploit special features of the C programming language. For example, numbers are stored in computer locations called memory addresses, which are then manipulated. This is a clever way to avoid computationally intensive operations like division. “Think of it like putting the wrong tag on something at the store and it convincing the employee but here it is C we fool,” explained computer scientist Daniel Harrington from the University of Toronto in a presentation.

From a mathematical perspective, the code is easily explained. To determine the inverse square root, you first make a guess at the solution (which is generally incorrect) and then refine that estimate through a set procedure. In this way, it gradually reaches better solutions.

None of this is groundbreaking or new. What is impressive, however, is that usually four to five iterations of the process are needed before the result is close enough to an actual solution. This process requires a lot of computing power. In Quake 3, the starting value—that is, the estimated number used in the first step of the process—was chosen so cleverly that only a single optimization step is necessary.

Seeking a magic number

The optimization steps correspond to the so-called Newton-Raphson method, which approximates the values at which a function produces an output of 0, or the root of functions, over many iterations. This may sound counterintuitive at first, since one wants to calculate the inverse square root and not just any zero. But the programmers employ a trick: they define the function to be approximated as the difference between the initial estimate value and the actual result. Through Newton-Raphson’s method, the error thus becomes progressively smaller, allowing one to get ever closer to the exact solution.

To think this through, imagine you want to calculate the inverse square root of 2.5. The algorithm starts with a certain guess: let’s say 3.1. To determine the difference from the actual solution, you square the initial value and divide one by the result. If 3.1 were truly the inverse square root of 2.5, then 1 divided by 3.1 squared would be 2.5. The actual result is 0.1. The difference is therefore 2.4.

The Newton-Raphson method reduces this difference over each iteration so that you gradually get closer to the exact value. Typically four to five such steps are needed to arrive at a reliable result. Yet Quake 3 reduced iterations significantly.

The key is in how the starting value for the Newton steps is calculated. The method’s algorithm essentially operates in three steps:

-

Take the given number whose inverse square root is to be calculated and convert it into a corresponding memory address (a location in the computer’s stored data).

-

This value is halved and subtracted from the hexadecimal value 0x5f3759df. This is the starting value for the Newton method.

-

Next, perform a Newton step.

Particularly mysterious is the cryptic string 0x5f3759df, which has since gone down in computer science history as the “magic number.” It is the reason why only one iteration is necessary to obtain an approximate solution for the inverse square root that produces an error of at most 0.175 percent.

As soon as the program code was available as open source, experts puzzled over the origin of that magic number. In a technical paper published in 2003, computer scientist Chris Lomont wrote: “Where does this value come from, and why does the code work?”

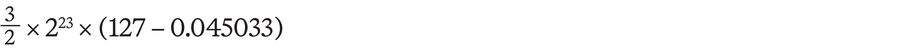

The hexadecimal number 0x5f3759df corresponds to 1,597,463,007 in decimal notation. By breaking down the individual steps of the program code, Lomont realized that he could obtain 1,597,463,007 through certain calculations. To make this math simpler, here’s one way to represent the calculation involved:

The values 3⁄2, 223 and 127 come from converting the number representations into C. But 0.0450465’s origin is less obvious.

Lomont mathematically investigated which value yields an optimal result for different inputs. In other words: Which starting value best approximates the inverse square root and should therefore lead to the smallest error? He arrived at a value of 1,597,465,647, which is approximately:

This corresponds to the values found in the Quake 3 source code. The result is quite close to the values found there.

When Lomont compared his results with those of the original, he encountered a surprise. In two steps of the Newton-Raphson method, his calculated constant actually worked better: the maximum possible error was smaller than with the value in the original code. “Yet surprisingly, after one Newton iteration, it has a higher maximal relative error,” Lomont writes. “Which again raises the question: how was the original code constant derived?”

In his calculation, the computer scientist had only considered which number would theoretically yield the best possible value, neglecting the number of Newton steps. In search of a better constant, Lomont repeated his calculation and optimized for the best possible solution for a single Newton step. He arrived at a value of 1,597,463,174, which is approximately:

When he put this result to a practical test, it actually yielded slightly better results than the magic number in the Quake 3 code.

Lomont noted in his paper that since both constants are approximations, either is a good option in practice. He added that he hoped to meet the original author of the constant to learn how they derived the magic number.

Online communities began a relentless search for this mystery person. Particularly dedicated to this effort was computer scientist Rys Sommefeldt, who first contacted John Carmack, the lead developer of Quake 3. Carmack was unsure of who coded this snippet and could only offer guesses, however.

Sommefeldt contacted some of the most prominent developers of the 1990s, who each suggested other possible authors without claiming authorship for themselves. It now appears that Greg Walsh, who worked for the computer manufacturer Ardent Computer in the late 1980s, introduced the magic number into the inverse square root algorithm. It then found its way into the Quake 3 algorithm via several other individuals. But exactly how the magic number was determined remains unclear to this day.

That’s not a particularly satisfying conclusion. Nevertheless, the story of the Quake 3 code—or at least the part that revolves around the inverse square root—is extremely fascinating. It’s astonishing how much effort and brainpower went into efficient software programming back then—a trend that’s often overlooked today thanks to current computing power.

This article originally appeared in Spektrum der Wissenschaft and was reproduced with permission.