The quirky geology behind Olympic curling stones

The rocks used in the Olympic sport of curling come from one island in Scotland and one quarry in Wales. What makes them so special?

Eve Muirhead of Team Great Britain competes against Team ROC during the Women’s Curling Round Robin Session on Day 13 of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games.

Justin Setterfield/Getty Images

From skating to curling, the thrilling sports of the Winter Olympics have plenty of science behind them. Follow our coverage here to learn more.

Athletes often have specialized equipment or apparel to make them run, swim, skate or ski their best, but curling takes things to another level. Curling rocks—as the round, roughly 40-pound stones are called—only come from two places on the planet: a little island in Scotland called Ailsa Craig and the Trefor granite quarry in Wales.

But what makes the rocks from these places uniquely suited for sliding across a rectangular slab of ice toward a bullseye target? And are these really the only places to find suitable stones?

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

To find out, Scientific American spoke with Derek Leung of the University of Regina in Saskatchewan, a mineralogist and avid curler who used to compete for Team Hong Kong. Leung has married his two interests by doing the first mineralogical analyses of curling rocks since 1890. “It’s been more than a hundred years since we had looked at them,” he says, so he wanted to see what modern science could tell us.

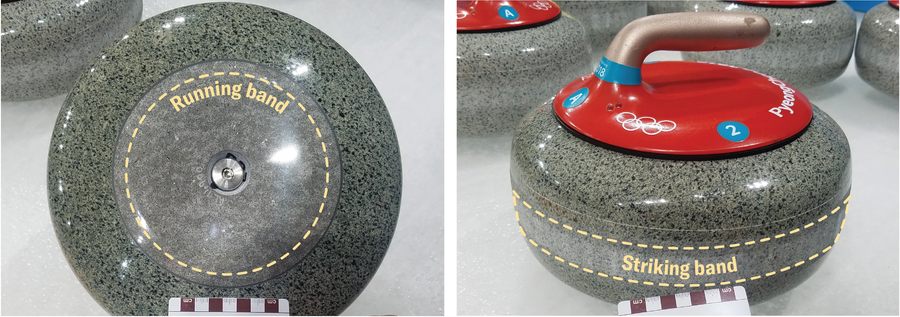

But before we get into that, let’s go over the two main parts of a curling rock: the running surface and the striking surface. The former is a ring on the bottom of the rock that skids across the ice, and the latter is a band around the sides of the rock that collides with other rocks (ideally knocking an opponent’s rock off the bull’s-eye or nudging your team’s closer to it).

Each surface needs specific properties to do its job. This is where Ailsa Craig and the Trefor quarry come in. The former has been used for curling stones since the early 19th century; the latter since curling grew in popularity after World War II.

Each place has two types of rock used for curling stones: Ailsa Craig common green and Ailsa Craig blue hone, and blue Trefor and red Trefor. All four types are granitoids, which are igneous rocks, meaning they form as magma or lava cools and crystalizes. Ailsa Craig’s rocks formed around 60 million years ago when magma pushed into a relatively shallow layer of the Earth’s crust during the rifting that formed the Atlantic Ocean. Trefor’s formed around 400 to 500 million years ago during a mountain-building event called the Caledonian Orogeny. Both are, geologically speaking, fairly young. “Having a young rock is probably a good thing because it means that it’s less likely to have incurred stresses related to different tectonic events” before it is subjected to the stresses of curling, Leung says.

Common wisdom has held that rocks from these two sources were ideal because they contained very little quartz, a brittle, silica-based mineral that would be less than ideal for expensive stones constantly knocking into each other. (Curling stones cost around $600 a pop, and they’re typically used for 50 to 70 years.) But Leung found that in fact all four rocks contain quartz. Yet under the microscope, “I found almost no fractures,” he says, likely because of their young age.

Ailsa Craig blue hone is commonly used for the running surface; manufacturers cut a circle out of the bottom of the main rock and insert a disk of blue hone. Leung found that blue hone has small, fairly uniform grain sizes. This is ideal for decades of sliding across the ice, because bigger mineral grains are more likely to get plucked out by the ice, leaving holes in the surface that could cause unpredictable behavior. Blue hone is also relatively nonporous, which means water from the ice is less likely to get in and cause fractures.

Ailsa Craig, a remote volcanic island located in the Firth of Clyde, off the west coast of Scotland.

For the striking surface, on the other hand, “you want to have larger differences in grain size,” Leung says, because “it prevents certain types of damage from occurring” when the stones collide. Ailsa Craig common green, blue Trefor and red Trefor are all good for this, which is why they’re used for the main rock; the striking surface is created by carving the main rock. The rocks for the 2026 Milano Cortina Winter Olympics will be made of Ailsa Craig common green and use blue hone for the running surface.

In principle, there’s no reason rock from other places couldn’t work for curling. After all, when that 1890 study was conducted, curlers used stone from all around Scotland, the sport’s birthplace. Ailsa Craig and the Trefor granite quarry probably became the go-to sources over time through some combination of their performance characteristics, tradition and standardization. And blasting is no longer allowed at Ailsa Craig, a now-uninhabited bird sanctuary, so another source would help keep curling clubs stocked in the future.

This is something Leung hopes to work on. An effort in Canada in the 1950s failed because the very black, igneous rock called anorthosite that was quarried from Northern Ontario started chipping soon after use. But with better knowledge of what rock works best, it might be possible to find a new source. “We could look for rocks that are formed in a similar environment as Ailsa Craig,” Leung says—maybe Nova Scotia, which is on the opposite side of the Atlantic rifting event that made the granitoids found in Ailsa Craig.

He hopes one day to work with quarries to get samples to analyze. If he finds any likely candidates, he would love to get them made into curling rocks and try throwing them down the ice to see what happens.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.