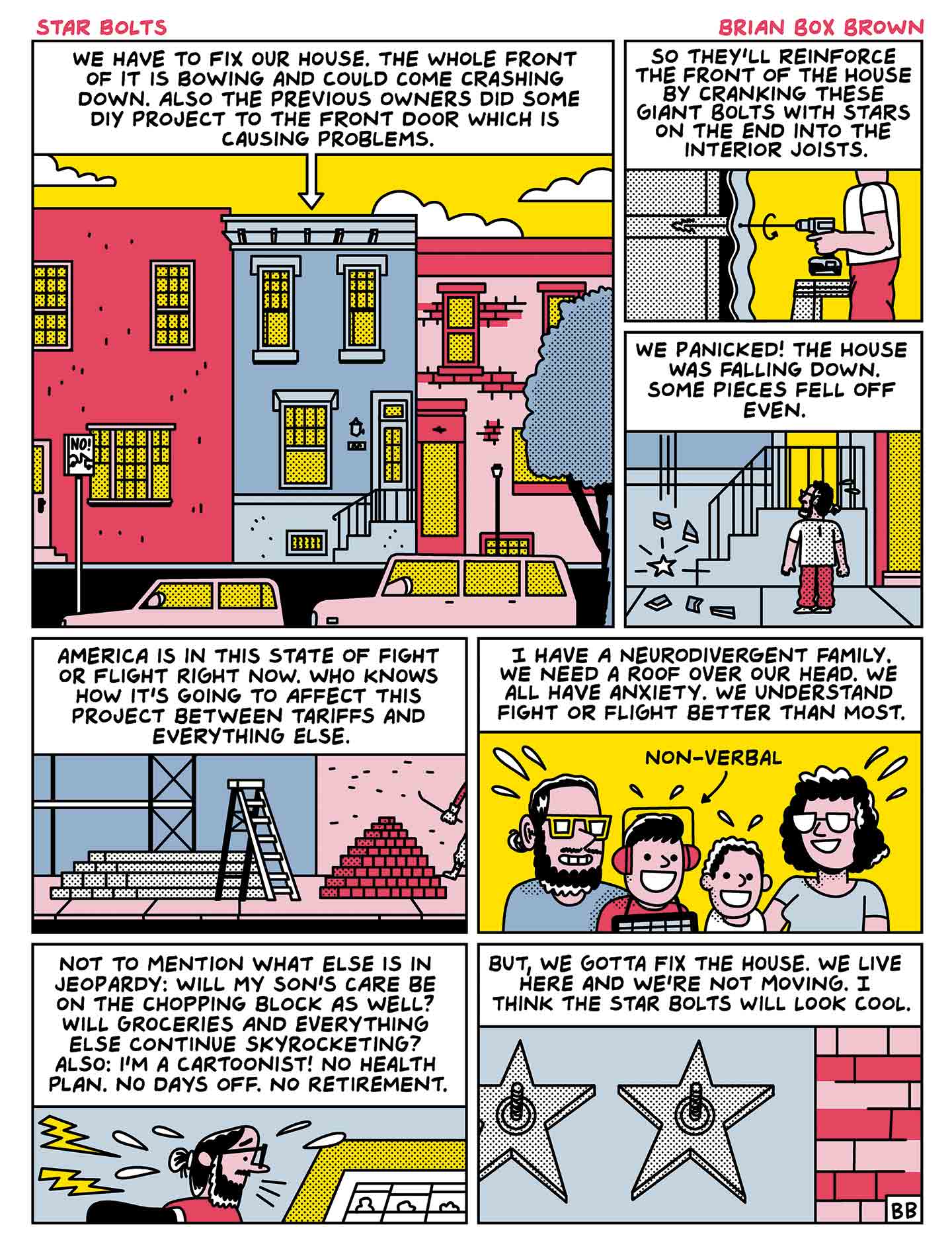

The country and the nation: Fifty writers and artists report on the states of our dis-union.

160th Anniversary Issue

Richard Kreitner

Let’s be frank: It’s a somewhat presumptuous name for a magazine. Adopting it may have been akin to what philosophers refer to as a “speech act,” meant to call into being the very thing referred to. Largely absent from pre–Civil War political rhetoric, which more often spoke of “the union” or “the republic,” the word nation appeared five times in Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address. Two years later, when the first issue rolled off the presses in July 1865, the Confederacy had been defeated and Lincoln murdered, and a fierce fight over whether the “nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” would indeed see “a new birth of freedom” was just beginning. The Nation was founded to see that struggle through—and we will.

By the 1920s, there was still something a little incongruous in a magazine so named devoting hundreds of pages over three years to an extensive meditation on each of the separate states. Penned by some of the most illustrious writers of the period—W.E.B. Du Bois on Georgia, Edmund Wilson on New Jersey, Sherwood Anderson on Ohio, Willa Cather on Nebraska, H.L. Mencken on Maryland, Sinclair Lewis on Minnesota, Theodore Dreiser on Indiana—the essays in that series, “These United States,” explored the rich history, geography, and character of those minor subdivisions supposedly effaced by the Civil War. The country was often depicted as “one vast and almost uniform republic,” the editors observed in an introductory note in 1922. But that left out what made American life interesting: “What riches of variety remain among its federated commonwealths? What distinctive colors of life among its many sections and climates and altitudes?”

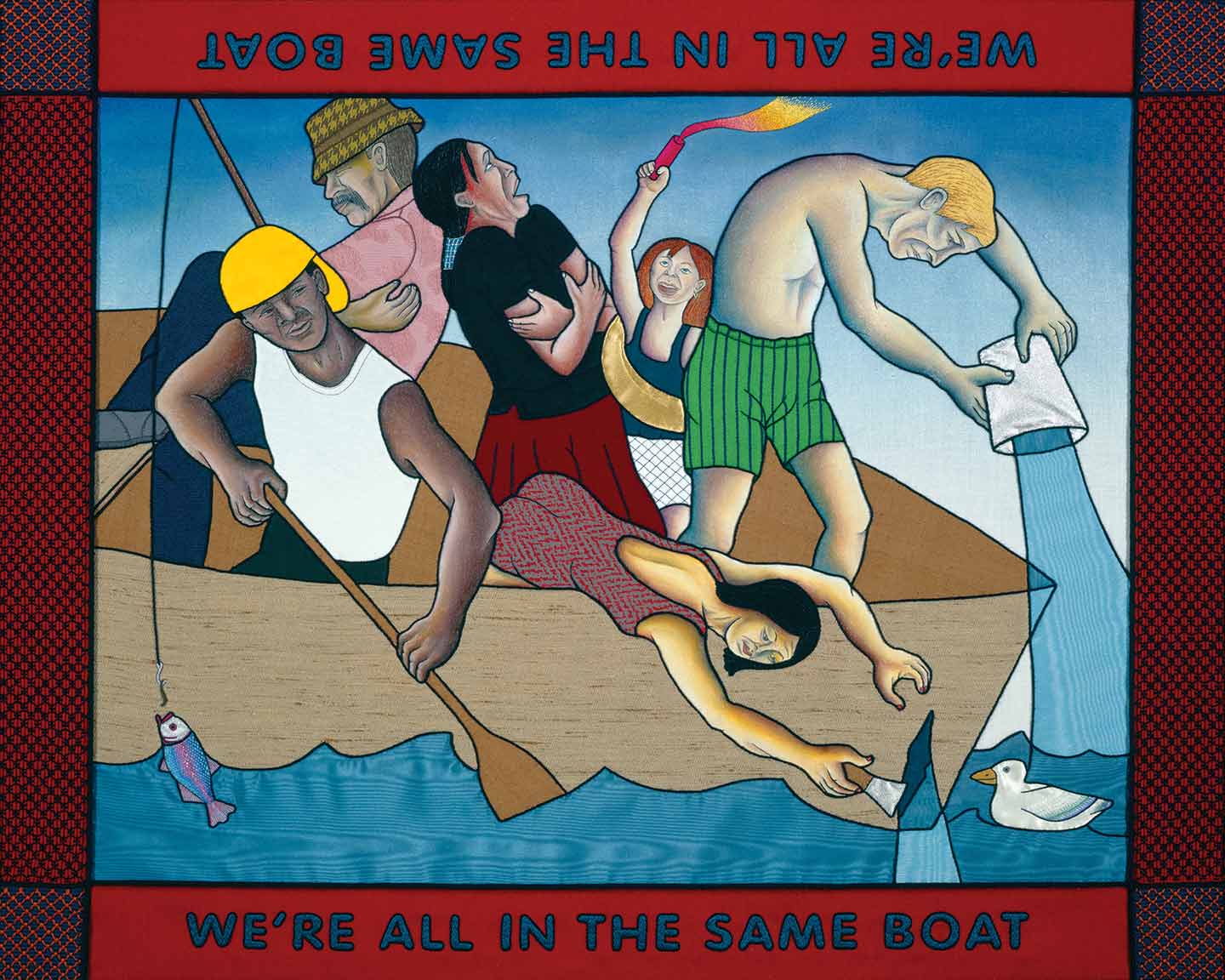

In perusing the following dispatches from “These Dis-United States,” as we’re calling the series this time around, you may well be struck by how similar the experiences of this moment are in many states across this bruised and battered land. Asked to address “the fraying of the ties that once bound us to one another as Americans (or, as often, did not),” 50 of our best writers and artists depict local textures, practices, landmarks, and institutions everywhere being gutted, steamrolled, defunded, eviscerated. Here we get firsthand testimony, from Maine to Hawaii, of the acceleration of a decades-long project to hollow out government at every level—and of the devastating effects of that project on our national life. Among other things, these pieces tell a story of the aggressive erasure of difference. Still, as Judy Chicago puts it in the title of her hand-embroidered contribution, “We’re All in the Same Boat”—even if some of us are doing everything we can to keep it afloat, while others, for profit or pleasure, try to capsize it.

The editors’ note from 1922 ends with a statement of hope that while “artificial…distinctions” between states would eventually be “assimilated,” more authentic differences would remain:

Though centralization and regimentation may be a great convenience to administrators, they are death to variety and experiment and, consequently, in the end to growth. Better have the States a little rowdy and bumptious, a little restless under the central yoke, than given over to the tameness of a universal similarity.

So, too, today. Many of the pieces that follow portray the states as the necessarily circumscribed plots in which the seeds of some new form of individual and collective liberation might take root—a new birth of freedom, quite different from that imagined by Lincoln and supported by the founders of this magazine, but one that can emerge only from local practices of connection, conversation, organizing, and experimentation—the rowdier the better. We are still calling this nation into being, making an old country anew.

Current Issue

Dixie, USA

Ashley M. Jones

in alabama, i learned the truth of human duality and i learned the truth of human tenderness. i learned that the river’s current is a currency we share but often abuse—think of the old iron bridge at the cahaba—there, above the waters which make us the most biodiverse, waters which literally make space for every little organism to live, eat, make babies, and die in nature’s way—there, men of the stars and bars planned to plant bombs, corrupt seeds in the belly of a church in birmingham. faced with so much wonder, the flow of the river filling their ears with the most raucous and peacemaking sound, how did their minds see anything like hate?

what flag makes the shape of this particular paradox?

the very first time the american flag made me swell with pride or fear or love or, if i’m honest, with tears, was the day i saw it hanging, strangely and swinging from the apex of the ladders of the fire truck which carried my father’s coffin. that day, a may first i’ll never forget, but which i wish would disappear from my memory, i saw the flag flying in the breeze, starkly bright against a gray, cloudy sky, my own body dwarfed in the black suv my cousin drove as we made our way from the funeral to the graveside service. the flag, which let me know my dad was a hero. the flag, which let me know that this country was grateful for his service, for every time he ran into a building’s deadly flames, for every time he started an iv, for every time he stopped someone’s overdose before it claimed them.

the flag, which also knew he was a black man.

which also knew, as a child, that he was hit by rocks and fists because the white children didn’t want integration. which also knew his great pride in his race. which knew his high jumps and joy when he hopped with his que brothers. which knew he had, in his very last job, his retirement job from birmingham fire and rescue as assistant chief, become the first black fire chief in midfield. in 2020. that flag saw me, too—

first black poet laureate of alabama. first person of color poet laureate of alabama. 31 and the youngest poet laureate of alabama. the flag saw me, too, in the alabama state capitol at my commissioning. was the flag there in 1930 when the first alabama poet laureate was commissioned? there we were, masked against a silent, brutal killer. there we were, without our hero in a chamber lined with the larger-than-life white portraits of so many governors who did not stand up for black people,

or, who literally stood in doorways to block us.

there, i was commissioned, little black me, and there was the podium where i gave my speech, and there, right above my sprawling afro, the marble plaque commemorating our state’s secession from the union. jefferson davis’ ghost slithered in the room. but the court square auction block ancestors were there. and my family was there, and my friends were there, and my father in heaven was there, and my poems were there, and my whole life was there as a testament that the whole confederate history could be swallowed like a piece of unchewed food and i could make use of its waste.

in alabama, i learned that there is something greater than a flag.

Ashley M. Jones is the first person of color and the youngest person to serve as Poet Laureate of Alabama. She is the author of four books of poetry, most recently Lullaby for the Grieving (Hub City Press, 2025).

When Boom Goes Bust

Tom Kizzia

Greenlanders weighing President Trump’s annexation offer might want to consider the present state of America’s existing resource colony, Alaska, as it struggles with flatlined budgets, crumbling schools, and an exodus of workers and young families.

We thought we were prepared for this inevitable period of decline in oil production. In 1976, after the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, the state created a permanent fund to invest some of the windfall for future generations. Annual dividends paid to all residents profoundly reduced income inequality.

Today, the Alaska Permanent Fund has grown to some $80 billion, and the earnings help pay for the government in a state with no income tax. But the fund doesn’t provide nearly enough revenue for both the state budget and the dividends, which remain popular across the political spectrum.

In 2018, Republican Mike Dunleavy strode into the governor’s office with a promise to double or triple everyone’s dividends. This would have required absurdly deep spending cuts, or general taxes like nearly every other state imposes. But Dunleavy swore to veto any new tax.

The problem is compounded by Alaska’s taxation rates on mining and oil production, which have remained low since resource companies effectively captured the legislative process in the 1980s. This year, Alaska expects to shave $600 million off of oil companies’ tax bills to compensate for low oil prices. Last year, amid a mining boom, the state actually paid miners more (through tax settlements) than it got back from license tax revenue.

Dunleavy’s solution? Ever more resource development projects, promoted by more state subsidies—including drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, building a $44 billion natural gas pipeline, and accessing untapped copper deposits with a 200-mile road along the untrammeled Brooks Range, right through the caribou-hunting grounds of Native villages.

Meanwhile, Native fishing camps sit empty because salmon runs have disappeared, and remote villages collapse as the permafrost melts—problems linked to burning the very fossil fuels whose extraction the state subsidizes. Tourism, a growth industry, has softened the anti-park sentiment that emerged on the right in the 1970s, but the insatiably expanding cruise industry is inspiring new resentments in coastal towns.

One source of optimism is Alaska’s ranked-choice voting system, which put moderate bipartisan coalitions narrowly in charge of the Legislature this year. And the state’s small population (less than 750,000) allows the kind of face-to-face campaigning that helped reelect US Senator Lisa Murkowski, one of the few independent Republicans in the MAGA-dominated Congress.

Dunleavy predicted a “golden age” for the state with the reelection of Donald Trump, but so far cratering oil prices have cost Alaska’s budget hundreds of millions of dollars. Deadlock, social decline, and life at the mercy of commodity prices may look unattractive to Greenland’s 57,000 residents, but the model evidently appeals to the Trump administration. Trump officials have reportedly considered offering annual $10,000 cash dividends to Greenlanders, paid for out of anticipated resource revenues, to replace the at least $600 million in free healthcare, education, and other annual subsidies that Denmark provides.

Watch out, fellow Northerners—the next “golden age” could be yours.

Tom Kizzia is the author of three nonfiction books on Alaska, including Pilgrim’s Wilderness, and a former Anchorage Daily News reporter.

Political Theatrics

Tom Zoellner

When the Arizona Senate’s Government Committee met in February to consider a bill mandating that cities and counties assist with ICE raids, state Senator Jake Hoffman (who is also a member of the Republican National Committee) took the opportunity to ham it up for the cameras, ranting about how “mass deportations are wildly popular with people who are in every party.”

If Hoffman sounded like he was auditioning for a job in the Trump White House instead of governing, he was only joining a troupe of lawmakers who are exploiting the well-known “C-SPAN effect” that has now arrived at Arizona Capitol Television: the propensity for legislative discourse to become more combative and emotional when it’s conducted in front of the cameras.

Say this for times of disunion: They create entertaining theater. In the run-up to the Civil War, congressmen of all persuasions paid close attention to how they were covered in the press. Many made incendiary floor speeches designed not to find solutions but to win the applause of distant audiences. The term bunk comes from an 1820 speech about slavery delivered by a representative from Buncombe County, North Carolina, who explained that he was not “speaking to the House, but to Buncombe.”

Such is now the dynamic on Arizona Capitol Television, a streaming service formerly watched only by lobbyists and government junkies. In Donald Trump’s second term, however, it has become a stage for Republicans to create viral clips that show their fealty to the MAGA agenda. Committee hearings, once restricted to the dull grind of process and the exchange of courtesies, have become noteworthy for their Buncombe quality.

“This year there’s a heightened sense of, I don’t know what you’d call it… assholery by the Republicans,” state Senator Analise Ortiz, a Democrat from the west Phoenix suburbs, told me.

While some see that assholery rooted in self-confidence, a better explanation might be insecurity. Arizona Republicans are keenly aware of the price to be paid for failing to live up to Trumpian standards. One of the very first US senators to be ousted from the GOP over such an offense was the seemingly untouchable Jeff Flake, who angered Trump in 2017 by publishing a MAGA-skeptical book called (in a nod to Phoenix icon Barry Goldwater) The Conscience of a Conservative. An ensuing Twitter barrage by the president sent Flake’s popularity diving and ended his reelection bid. A similar purge of those seen as insufficiently ardent ring-kissers has virtually eliminated moderate Republicans from the Arizona Legislature.

The old-school conservatives who used to compose the ideological backbone of Arizona government have effectively disappeared, offering barely a murmur of dissent to the MAGA takeover of the Legislature—and of Arizona Capitol Television. “It’s so transparent what they’re doing,” lamented Stacey Pearson, a longtime Democratic consultant. “These are scripted clip-and-share moments. The Republicans are hoping their antics go viral, but this performative governing shtick is likely to backfire on them.”

Tom Zoellner is the author of Rim to River: Looking Into the Heart of Arizona.

Child, Laborer

Alice Driver

Walk the land in rural towns like Green Forest, Arkansas, down dirt roads among clusters of homes, and you will hear Spanish, Marshallese, Vietnamese, Laotian. A woman from Guatemala will tell you that rent is $300 a month as she sits on a sagging couch in a town of nearly 3,000, where almost half that many people work at Tyson’s processing plant.

The children arrived as unaccompanied minors. The children speak Indigenous languages. The children speak Spanish. Teachers whisper about some students, weary from the night shift, who sleep through class. Eventually, many disappear from school, their lives given over to the night shift. These kids live in the shadows, afraid and silent. But if you stay late enough, after dark, you will see them leaving for work, like ghosts in the night, heading to the plant where they will handle skin, fat, bone, and blood.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Politicians say that children will solve the labor shortage. As Project 2025 puts it, “Some young adults show an interest in inherently dangerous jobs.”

In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which imposed restrictions on child labor. Yet my home state of Arkansas has already begun rolling them back. In 2023, Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed the Youth Hiring Act. Arkansas no longer verifies the ages of children between 14 and 16 who take a job. Sanders’s communications director declared parental permission an “arbitrary burden,” so the paperwork that served as a record of the names and ages of minors working in the state no longer exists.

In 2023, a US Department of Labor investigation found six children between the ages of 13 and 17 working at a Tyson plant in Green Forest. In 2024, Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families published a report noting that child labor violations in Arkansas increased 266 percent between 2020 and 2023. In October 2024, a woman in Green Forest filed an anonymous complaint to alert authorities to child labor problems. The woman, a mother of middle schoolers, overheard children between 11 and 13 discussing their employment at the Tyson chicken processing plant. The night shift is also known as the cleaning shift, when hazardous chemicals are used to clean the large, sharp machinery. The complaint said she allegedly heard the children discussing whether they could get their paychecks from the ATM.

These children who move through the Arkansas night, their small, strong hands doing dangerous jobs, should haunt us.

Alice Driver is the author of Life and Death of the American Worker: The Immigrants Taking on America’s Largest Meatpacking Company.

Magic and Survival

Julian Brave NoiseCat

“Our culture is our superpower.” That’s what my friend the Cook Island artist and voyager Numangatini Mackenzie told me before the lights went down for the world premiere of Shrek translated into te reo Māori, the first language of Aotearoa (New Zealand). As we talked, kids bustled up and down the bleachers and around the floor of the gymnasium, which had been converted from basketball court to a theater for Māoriland, an Indigenous film festival put on in Otaki, a sleepy town 45 minutes northwest of the New Zealand capital, Wellington. All around, ahead, behind, to our left and right, the hum of Māori, with their tattooed arms and faces, their long hair and high buns, and their bodies adorned in bone, shell, and greenstone, speaking that percussive vowel-strewn Eastern Polynesian tongue, te reo, or “the language.”

To my shock, the little ones were fluent. I will never forget the coo of a little Māori boy calling the dragon a “taniwha.” Meanwhile, the elders seemed to chew the language as they tried to find their words, which they tended to intersperse with English.

Across the Native world, there are few gymnasiums full of Indigenous peoples speaking our languages. And in the few where we do, it is almost always the opposite, with younger generations struggling to understand and communicate with our elders.

Less than a lifetime ago, te reo, like many other languages, was running headlong towards what is widely considered a foregone conclusion for Indigenous peoples and our cultures: death.

But that night, as a gym full of grinning Māori took in the tale of a green ogre and talking donkey rescuing a princess—first from that taniwha, then from Lord Farquaad, and finally from the prejudices of a magical society hellbent on destroying all magical things—with plot points, pathos, and punch lines all delivered in their language, you would never have known it. Today, there are te reo actors, te reo rappers, te reo broadcasters, te reo street signs, te reo dissertations, te reo memes. And now a generation of Māori tykes raised in te reo.

To me, this feels like a dream. I spent the last year-and-a-half promoting my first film, Sugarcane, which documents the unspoken atrocities and enduring intergenerational traumas wrought by the segregated missionary school where my family was sent to unlearn our Indian language and ways. Virtually all Indigenous peoples across this continent were torn from our cultures and one another by similar institutions. “Kill the Indian, save the man,” that was the idea, according to the American architect of the policy. My travels with Sugarcane took me from Indian reservations across Canada and the United States to the Canadian Parliament, the White House, and the 97th Academy Awards, before it landed me in Aotearoa. It was, at times, a hard journey, and not just because it was so personal. How do you convey to audiences who know nothing of this history that there was a national—no, global—conspiracy to wipe Indigenous peoples and our cultures off the face of this earth? That the last of these schools for Indigenous children didn’t actually close in the 19th century; they closed in 1997? That this is why we don’t understand our elders, our languages, and ourselves? That it could happen again? That maybe it already is happening?

As I write this, my flight from Aotearoa is touching down in Los Angeles, the American factory of global popular culture built in no small part on Western tales of gunslinging cowboys slaughtering savage Natives. California epitomizes many quintessentially American phenomena, like Hollywood, Silicon Valley, and killing Indians. In fact, arguably no state in the union did the last better. Between 1769 and 1800, gulag conditions in Spanish missions cut the coastal California Indian population in half. Not to be outdone, during the first decade of American rule in the 1850s, Californians subjugated as many as 20,000 Natives, including 4,000 children, using them as farm hands, domestic servants, and sex slaves. Through 1873, the state bankrolled militias to the tune of $1 million. Those militias murdered as many as 16,094 Indigenous peoples, according to University of California Los Angeles historian Benjamin Madley. When the ’49ers came to pan for gold and hunt Indians, there were some 90 languages spoken in the state. Today, half of those are endangered. The other half are extinct.

Sometimes, I don’t know how our people survived. And I’m never certain how we should proceed. But my friend Numa down in Aotearoa has his theory. “Our culture is our superpower,” he said as we sat in a room full of Indigenous peoples who were supposed to be culturally dead, lit up with laughter as a magical story told in a language they were supposed to forget unfolded on the big screen.

Julian Brave NoiseCat’s first film, Sugarcane, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary. His first book, We Survived the Night, a work of creative nonfiction on Indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada today, will be published by Alfred A. Knopf in October.

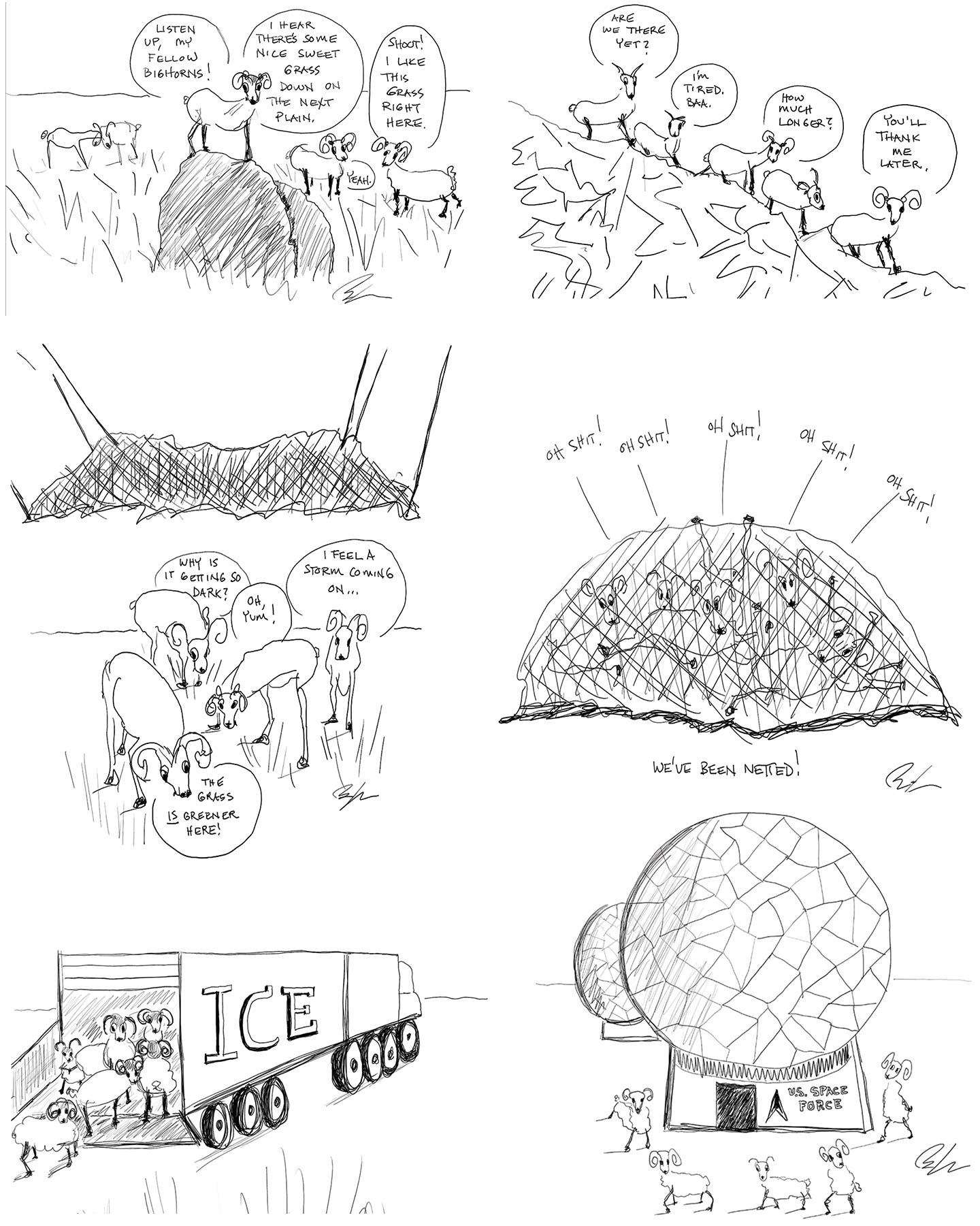

The Bighorn Trap

Sarah Boxer

A couple months ago, I watched a local newscast about efforts to revive and disperse the population of Colorado’s state animal, the bighorn sheep. The Department of Parks and Wildlife lured the bighorns near Colorado Springs with tasty treats, dropped a net on them, and took them to a distant plot of land. The video was upsetting. It showed the hapless bighorns freaking out in the net before being wrestled to the ground and loaded into trucks for the trip to a former burn scar west of Pueblo that’s now grassland. But when the sheep got to their new home, I have to admit, they looked pretty darn happy.

Still, the video left me with a sinking feeling. Something about those bighorns in the net reminded me of another endangered population two hours north. Shortly after Trump’s second inauguration, the Pentagon designated Buckley Space Force Base in Aurora as a “processing center” for undocumented immigrants. By April 2025, Colorado Public Radio reported, Immigration and Customs Enforcement had broadened its efforts in the state, and many immigrants with no criminal record were being “caught in a wide net.” I know this analogy between trapped animals and trapped humans is imperfect and unsettling in its own right. But a net is a net. And as disturbing as that bighorn video was, it’s much more disturbing to realize that Colorado’s immigrants are being treated less thoughtfully than the freaked-out sheep. Another key difference: All the bighorns were soon set free.

Sarah Boxer is the cartoonist behind In the Floyd Archives, Mother May I?, Hamlet: Prince of Pigs, and Anchovius Caesar.

Getting Back to Work

David Bromwich

For the past 25 years, we have been divided in an alternating pattern of roughly 51 percent majorities, and the same mistake is made by each successive winner: Go all the way with your program while you can—implement now, explain later. What the winners have forgotten is that you cannot govern for long without the consent of the 49 percent.

Democratic lawmakers for the time being are stunned, scattered, and immobilized, in a region between bewilderment and dismay. The more serious among Republican lawmakers have shown themselves docile in obedience to the edicts of a president who is acting more like a dictator than most people, even in his own party, seem to have thought possible. But the serial enormities of Donald Trump’s first 75 days form a pattern that is not built to last. A few Republican lawmakers—it only takes a few—will come to oppose the most clearly anti-constitutional of his orders; and Democrats will relearn a language that does not triangulate the mental habits of Hollywood, Silicon Valley, and Wall Street.

As surely as Joe Biden was self-deceived when he thought no one would notice three years of uncontrolled immigration and the conduct of new wars two at a time, Donald Trump will overstep the limits of popular sentiment with exorbitant tariffs, the capture and transportation of US residents to foreign prisons, and the firing of government workers where the loss can be felt and resented by millions of ordinary people on the other end. What tactics can Americans who want a saner society use?

Speak in a language that is political rather than therapeutic. Do not expect people to believe that “trauma” is a daily risk for all Americans who are not white. Try, in fact, to speak to all Americans—not as the sum of their racial, ethnic, religious, and gender-identified parts, but as people who want to get on with their lives unmolested and reasonably healthy. For the purposes of democracy, recognize that lawfare was a shortcut to political power that deserved to fail. As for “resistance”: The job of an opposing party is opposition. As soon as it acquires a double identity as half party, half movement, anyone who objects to either half will be tempted to give up the whole.

A few obvious maxims follow for the defenders of liberal society. Be specific in your criticisms of policy. Stake out two or three positions of principle—on free speech, or government by law, or freedom from cruel and unusual punishments—and state the practical effect of those positions. For example: “You should never lose a job for an idiocy you published online under the age of 18.” Refer steadily to acts and the officials answerable for those acts, and, wherever possible, omit the shorthand “Donald Trump”; it may seem like a labor-saving device, but it has failed before, and it is time to get back to work. It is not self-evident, nor should it be, that you are the people who deserve to govern. Those who would govern have a responsibility to persuade.

David Bromwich teaches literature at Yale University.

New World Sourdough

JoAnn Balingit

Since the 2024 presidential election, I have bought no bread. It’s not a fast. Not grief. Not “some weird penance,” as a friend described her failure to sing in the shower since Election Day. It’s a freedom.

“Mother Delilah,” as I named my sourdough starter, is soothingly predictable: She behaves just as the baker Bryan Ford said she would in his book New World Sourdough. She’s ritual, a prayer.

Since November: sourdough boules, bagels, waffles, English muffins. Sometimes two baking days a week. We make music, poems, syllabi, Facetime calls, gardens, love. We make meals for loved ones. The youngest member of this household dances and does his own laundry.

As I stretch the fabulous mass in my hands, turn the bowl a quarter, stretch and turn again, I wonder: When I circle the wagons in this way, do I isolate myself from others? Am I embracing reality, or ignoring it?

It’s hard to ignore disunity, living in Delaware. My state embraces having been the first to ratify the Constitution and enter the Union. Less often do we share that it did so as a slave state and continued to hold people in bondage through the Civil War, while almost 12,000 Delawareans fought for the Union. An estimated 2,000 Delawareans fought for the Confederacy meanwhile.

I think of “Red Hannah,” the whipping post displayed at the Sussex County Courthouse until 2020, when protests forced it down. The last public flogging was in 1952, and Delaware had corporal punishment on the books until 1972, long after it was banned in other states. Cut almost two centuries ago, the Delaware & Chesapeake Canal splits the state into northern and southern halves, and that water continues to roughly delimit the social and political divisions in the state today. Delaware has more to do with the history of American disunion than we like to think.

With the blade of my palm, I flip the dough onto the counter and press my bench knife through its soft center to create two loaves.

The word disunited makes me think of little plots of forested land surrounded by developments of tract homes and many-laned roadways. And it makes me think of our Delaware subspecies of Eastern box turtle. I used to see them all the time. Fifteen years ago, one lived in our yard and migrated across the road into our neighbors’ shrubs each morning, then back to our house each evening. Now I have not seen a common box turtle in five years. Since 1968, the box turtle has declined 75 percent in the Ecology Woods, a University of Delaware 35-acre research site, indicating that it is vulnerable to extinction statewide. Its habitat is being torn apart.

In my kitchen in northern Delaware, this defiant bread is already rising. Amid fragmentation, I am here for those who need me, here for those whom I need: family, friends, artists who matter so much to me. We keep us safe.

New world, I think. Future. Hang on, threatened trees. Hang on, sacred rock. Hang on, sturgeon. Hang on, hatchling turtles. I love you, cypress springs. Hang in there when I am gone, my beloved granddaughters.

Living in isolated patches, confined to itself, a species cannot survive. Hang on.

JoAnn Balingit served as Delaware’s poet laureate from 2008 to 2015. Her poems and essays appear in Poetry, The Common, McSweeney’s, and elsewhere.

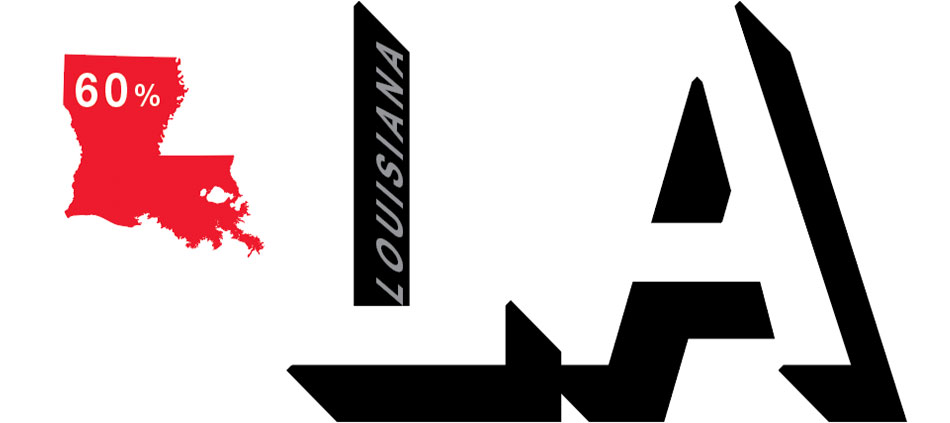

Crocodile Tears

Lauren Groff

Floridians who have been paying attention predicted the current coup that’s taking place in Washington, DC. After all, we in the Sunshine State have been slowly crushed under similar authoritarian forces for years. Ron DeSantis is only the most recent of Florida’s leaders who have been proudly and loudly hostile to their own citizens, eliminating DEI programs, choking out public education, and waging wars on books and people’s uteruses and the LGBT community and the environment. DeSantis has maniacal dreams of developing our super-fragile protected ecosystems into golf courses and hotels—of all the idiotic things to sacrifice the manatees to. I live in Gainesville, in the north-central part of the state, home to the University of Florida, and for years the school has been shedding brilliant academics who couldn’t bear the inanity of trying to teach here. Meanwhile, my friends who work in the nonprofit sector are anguished because even progressive nonprofits, to punish Floridians for their choice of leaders, are starving the state of philanthropic funds—which, of course, ends up hurting not the leaders but the people who can no longer be served. Our state has been bleeding out. We have gone wan and dizzy with it. This confuses non-Floridians into believing that wan and dizzy is our natural condition.

That said, not all Floridas are the same. Geographically, this state is larger than Greece or South Korea; if it were a European country, it would be the 10th-largest in terms of population, just behind Poland. This state is so large, so unruly, that our realities will always be fractured. This past March, my younger son and I went to Miami Beach for spring break. It is always discombobulating to go from the scrub pines and swampy subtropics of north-central Florida to tropical Miami, with its man-made beaches, its signs in Spanish and Haitian Creole, its masses of tourists with blistering sunburns. But this trip showed me a stark divide: The feeling of doom I’d carried around in the north, constantly upheld by my righteously enraged neighbors, vanished in the city of hedonism. There was no protest graffiti, nobody marching, no billboards—no indicators at all of the crisis the country is in. I was startled enough about this that I asked my food-tour guide, a Macedonian immigrant named Faruk, about the situation. He said gently, “In Miami, nobody cares about anything that happens outside of Miami.” When I asked him why, he smiled and said, “Money.”

Lauren Groff is the author of five novels and three story collections, including Brawler, which will be published in February 2026.

Not So Divided

Hannah Riley

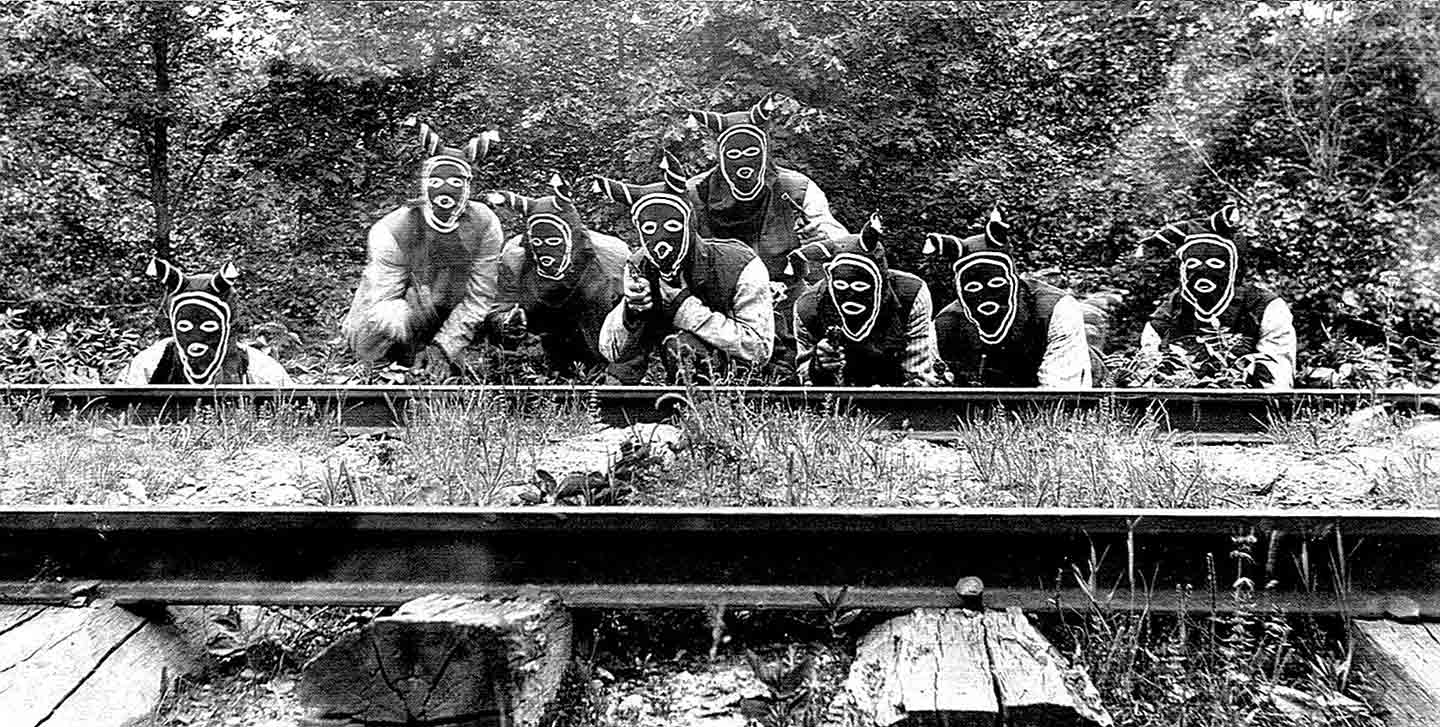

The state’s response was swift and harsh. It brought a sweeping RICO prosecution against 61 people, criminalizing acts of mutual aid and labeling protest as terrorism. A forest defender was killed by police, shot 14 times in their tent. Millions of dollars were wasted, the referendum was mired in an appeals court, and acres of forest were drowned under concrete. The end result? The facility was built. The movement fractured.

That’s one way to see it.

But, ultimately, to frame this story as one of a movement unraveling is to miss what’s happened. The intensity of the state’s repression correlates to the intensity of the popular opposition. It proves that we are not as divided as those in power need us to be.

Nowhere does the current state of disunion seem more evident than in Georgia, home to the widely protested Cop City, a $120-million-plus police militarization center. Years of sustained opposition had worked to block its construction in a Metro Atlanta–area forest: Land defenders lived in the trees they hoped to save; protesters destroyed machines that were to be used to raze the forest; a coalition tried to block construction through a democratic referendum.

If the people of Georgia wanted Cop City, its backers would not have needed to meet protesters with riot gear and police dogs. They would not have needed to treat a march in which people carried puppets and planted seedlings as a military confrontation, responding with flash-bang grenades and tear gas. The state would not have sent armed police to raid the encampments, to tear down kitchens and gardens and mutual aid tents. They would not have set up surveillance cameras outside protesters’ homes.

The overblown response came because the opposition to Cop City pulled back the veil on what policing is, revealing to more and more people the ways in which public money is funneled into expanding state violence while communities go without basic needs. People began to understand that the police state is not a response to chaos but a machine designed to manufacture it, to ensure that people remain fractured, isolated, and unable to build the kind of power that threatens the status quo. Cop City became a national flash point, uniting us across struggles and geographies. Residents of other cities began to draw connections to their own fights, recognizing that the same narratives were playing out in their hometowns, too.

As this country descends further into fascism, police will not be there to prevent harm or address these crises. At every site of resistance, from eviction blockades to deportation defenses to demonstrations in the streets, police will defend capital and state power with military-grade weaponry and surveillance technology. The Stop Cop City movement was more than just a protest and bigger than Atlanta: It was the convergence of many different struggles. It made clear that we are not breaking apart; we are holding together.

Hannah Riley is a writer and activist based in Atlanta.

Outlying Islands

Tom Coffman

For reasons that are both historical and intensely contemporary, Hawai‘i feels increasingly out of place in a discussion of the 50 federated states.

First, consider its separate history. Settled by Polynesians between one and two millennia ago, its disparate islands were slowly united into a complex chiefdom, while enduring a demographic cataclysm on contact with the West. Penetrated by Christian missionaries in the early 19th century, Hawai‘i evolved into a constitutional monarchy. Beleaguered by the seagoing imperialisms of Britain, France, and Russia, it was taken over step-by-step by the United States. Retooled into an armed fortress, Hawai‘i became the target of the attack that clinched the United States’ participation in World War II, during which it was placed under martial law. In the aftermath, a radical union movement and the Democratic Party took control of Hawaiian politics. Pulled by the imperatives of the civil rights movement, pushed by the Cold War, Hawai‘i became, in 1959, the first island state of the US and the first majority Polynesian- and Asian-ancestry state.

Since the mid-1960s, Hawai‘i has been perpetually conflicted by the speed and scale of development in the state and the degradation of its intangible resources. Partly as a response, partly from an instinct for survival, Native Hawaiians began making a startling resurgence in the mid-1970s. Lands and lifestyle have been protected by widespread protests. Suppressed history has been unearthed and popularized. Cultural practices have been retrieved, revalued, and normalized. The Hawaiian language has been rescued from the brink of extinction, and Indigenous rights have been incorporated into state-level common law. In a stunning project that has gone global, ancient practices of oceanic voyaging by non-instrument navigation have been revived.

Today, Hawai‘i is one of the bluest states. But it is also a semi-separate outlier with a sturdy core of shared values. Against this history, Donald Trump emerges from stage right as an oddball caricature of the United States at its worst. When he invokes President William McKinley as his role model, he cites the bumbling man who, to the dismay of Native Hawaiians, signed the resolution of unilateral annexation. When he speaks of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a time of great wealth, he reminds islanders of their long fight against the corporate stranglehold on the territorial economy. When by executive order he declares English the country’s official language, he challenges Hawai‘i’s constitutional designation of both English and Hawaiian as official languages. As he pursues his war against diversity, equity, and inclusion, he attacks the core values of Hawai‘i.

Turn any stone. In matters ranging from the plummeting numbers of Canadian and Japanese tourists to the rise in sea levels and the protection of species, Hawai‘i is predisposed to—is being driven toward—a greater self-sufficiency, not unlike other small countries around the world.

Tom Coffman is an author and documentary producer working on Hawai‘i politics, Hawaiian nationalism, and the Asian diaspora.

Vouchers vs. People

Luke Mayville

Earlier this year, for the first time in state history, Idaho lawmakers enacted a school voucher law that siphons funding from public schools in order to subsidize private school tuition. It was a tragic moment for the state’s public school system and an even worse moment for the state’s democracy.

House Bill 93—Idaho’s tax-credit-based voucher scheme—was overwhelmingly opposed by the public. In the first hearing on the bill, hundreds of Idahoans submitted testimony; citizens against the bill outnumbered those in support by a 10-to-1 margin.

The pattern continued after the bill arrived on Governor Brad Little’s desk. Before signing it into law, Little received tens of thousands of calls and e-mails, with 86 percent opposed to the bill. He signed it regardless.

What mattered more than the will of the people was the influence of billionaires like Betsy DeVos and Jeff Yass, who have financed aggressive smear campaigns against pro-public-education legislators in both parties.

What do these billionaires want? Beyond the push to privatize education and to save children from secular, liberal “indoctrination,” there’s also what the journalist Jennifer Berkshire and the scholar Jack Schneider describe in their book The Education Wars as an attack on the basic ideal of free and equal citizenship—“part of a broader effort to undermine the American commitment to educating every child, no matter their circumstances.” The anti-slavery politician Thaddeus Stevens once called public education “the great equalizer.” The oligarchs would prefer that we not be equalized.

In Idaho, the people’s fight against vouchers isn’t over. Pro-voucher groups have made clear that their next goal is to remove all guardrails from the new law and to expand the program from its current $50 million per year to an estimated $339 million per year—enough to decimate funding for public schools.

Yet the ground is fertile for a countermovement. In the wake of the bill’s passage, with an unprecedented level of public awareness and outrage tied to the issue, supporters of public education planned town halls in every region of the state and launched a movement to demand “Not a Dollar More”—no new tax dollars for an expanded voucher program. At a town hall in rural Payette County, a local superintendent predicted that House Bill 93 would turn out to be “our Pearl Harbor moment, when we wake up and we see the danger.”

One can only hope. In Idaho and in every other state being steamrolled by the billionaire-driven voucher agenda, it will take a reinvigorated movement to protect the integrity of our public schools. That movement will need to be cross-partisan, and it will need to span the urban/rural divide. Most importantly, it will need to be a movement that doesn’t merely defend the status quo but reclaims the highest purpose of public education—in the words of the writer Marilynne Robinson, “the old project of creating a free people.”

Luke Mayville is a cofounder of Reclaim Idaho, an organization that has spearheaded successful campaigns to expand Medicaid and increase funding for public schools.

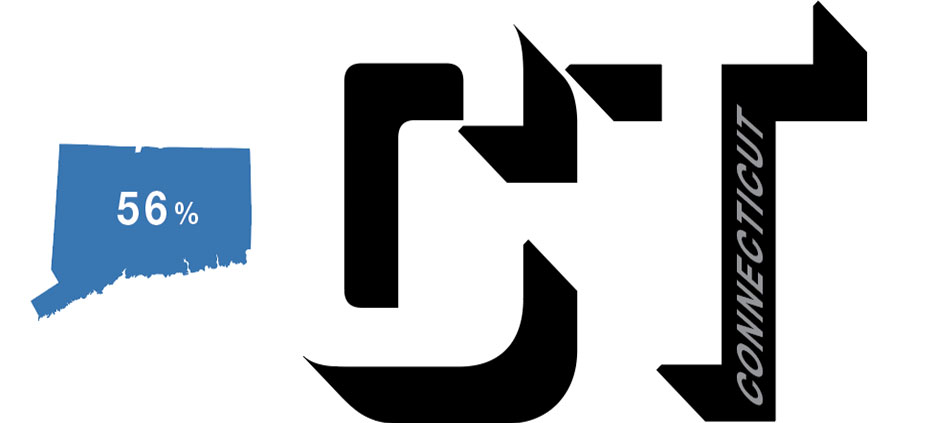

Blue Island

Chris Ware

In retrospect, driving with my 12-year-old daughter from our home near Chicago to an empty cornfield in southern Illinois to see the 2017 total solar eclipse, I should’ve been a little more alarmed by the number of Confederate flags we counted along the way. Four years later, when the pandemic seemed to have eased and we wanted to just go somewhere, anywhere, a day trip through central Illinois took us past not only more Stars and Bars but also “Trump 2024” placards and Trump-as-Rambo banners flapping over apartment balconies, as well as “Piss on Pritzker” lawn signs—all of which seemed a little overdone, given how laughably Trump had emceed the pandemic. (Also nasty, since I’d thought Governor JB Pritzker’s daily briefings were a heartwarmingly awkward spectacle of human anxiety and vulnerability, the corn-fed answer to New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s officious, patronizing scolding.)

Illinois basically has two regions: Chicago and “downstate.” Dense Chicago is reliably Democratic, whereas downstate skews conservative, but rarely enough to flip the electoral switch. (The last time Illinois voted for a Republican president was in 1988.) A fragment of a street called Blue Island Avenue still runs southwest from Chicago toward the town of Blue Island (the name apparently inspired by the low moraine that early-19th-century travelers could see gently bellying up from what Frederick Law Olmsted called the “flat, miry and forlorn” Illinois landscape), a place that was then a day’s wagon ride to the city, where beleaguered immigrants could stop for a rest and a beer. Overlaid on the scar of a Native American trail, the route endures as a diagonal slice of space-time through the gridlocked blocks of Chicago and its suburbs.

“Blue Island,” however, could just as easily describe our state, bordered to the north by purple Wisconsin and to the east by reliably red Indiana. Illinois has the second-highest property taxes in the nation, and my painter and sculptor friends who migrated to Indiana over the past few years didn’t do so because of the weather. We’re losing population at an alarming rate: Between 2010 and 2022, Illinois disgorged more people than any other state (and, embarrassingly, many of them were African American, in a sort of reverse Great Migration to a more affordable—and less Chicago-level-policed—South).

Nowadays, my drive to the empty eclipse-viewing cornfield seems ominous. I find myself second-guessing my words, my thoughts self-braking. Did downstaters feel the same way during “cancel culture” and “woke” DEI? How can it be that nearly half of the American population voted for all of this?

I’m originally from Nebraska, and I love the Midwest. The brown-and-gray humility of its homes and streets, its flat talk averaging out from all corners of the world. I realize I live in a blue state, if not a blue island. But how did we all let ourselves get so red with anger at one another?

Chris Ware is an artist, writer, and regular contributor to The New Yorker. A traveling retrospective of his work began at the Centre Pompidou in 2022 and concludes this year at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona.

Who’s Here?

Sofia Samatar

In the national imagination, Indiana is a place of comedy and horror. The lovable oddballs of Parks and Recreation make their home here, as do the children of Stranger Things, whose small town is menaced by an alien intelligence. This makes sense, as Indiana is closely associated with home: the exasperating home you ran away from, the vulnerable home you want to protect. It flickers in the heartland, where candlelight gleams through the sycamores.

Snow is falling on the first day of spring in the town where I was born. I walk with my head down, plowing into the wind, the Indiana stride. Sour joy at the toughness it takes. Other people have placid weather; they’re spoiled, shiftless—they wouldn’t last two weeks in this cold and cloudy dark. In her apartment in the retirement home, my mother picks out hymns on her electric keyboard. Over a jigsaw puzzle, we reminisce about the lost. Remember my cousin, who died a few years ago: his exuberance, his love of NASCAR, the noise and hot metal smell of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, eating fried chicken, tossing the bones about—that really got him, the schoolboy delight of throwing your trash on the ground. Remember my father, gone for a decade now, and how when I was a baby his coworker at the rubber factory called the cops on this African immigrant, accusing him of cannibalism. The officer pulling my dad from the line, the stares, the questions, the comedy and horror.

Of the many folk etymologies of the nickname Hoosier, my favorite traces it to “Who’s here?”—supposedly the call of early settlers when a stranger came to the door. It holds the echo of a knock-knock joke and the jumpiness of a scary movie: Who’s here, who’s already inside?

In the dining room of the retirement home, we eat delicious ribs that fall apart in your mouth and overboiled broccoli that falls apart on your fork. Pensioners pass with walkers, nodding their bleached, benignant heads, talking of church, crochet patterns, the granddaughter coming to fix the e-mail, and suddenly I wonder if there’s something profound in the TV versions of Indiana, a truth that can take form only in this folksy atmosphere. The modest job in the parks department with benefits, vacations, and the prospect of a dignified retirement—it’s not a joke, I realize, but a national nostalgia. The horror show, too, speaks to our common crises, dramatizing mental illness, experiments on children, a rotting landscape, and a predatory virtual world.

After dinner, snow is still whirling outside my mother’s window, bright in the beams of the back-door light. The bell rings. It’s her students, a middle-aged immigrant couple she volunteers to help with English once a week. Smiling, deferential, they brush off their coats. A lesson begins at my mother’s table, words detached and striving to find their grammar, soft, insistent flakes of language filling the air like snow. “I am.” “He is.” “She is.” “They are.” “We are.”

Sofia Samatar is a writer of fiction and nonfiction, including the memoir The White Mosque, a PEN/Jean Stein Award finalist.

Shrink the Aperture

Kaveh Akbar

The evergreen question of “How shall I live?” can feel immobilizing amid the calculated chaos of a despotic regime. So, too, can the unsatisfying mundanity of the only authentic answer: One moment at a time.

When the aperture on living gets too big, my instinct is to escape. Drugs and booze were great for that, allowing me to hover in blissful repose above my life’s unmanageability. But in recovery, I’ve lost my privileges to such luxurious flight.

What I have now is the ability to shrink my aperture. What I want is to arrest global fascism in its tracks and melt down every gun and instrument of war. But first: I will finish typing this sentence. If even that feels like too much, I can breathe in, then breathe out.

There is a desire now, I think, to find proportionally big, monolithic solutions to the big, monolithic evils of our murderous age. But waiting for superhero solutions to arrive and save us can diffuse our commitment to the trillion tiny, unsexy daily actions that actually make our lives bearable. Yeats on the Irish Civil War: “We had fed the heart on fantasies, / The heart’s grown brutal from the fare.”

I live in Iowa and teach at a big state university directly in the crosshairs of the Trump regime. I’ve not witnessed any capitol-storming insurrections yet, but I have stood with a small group of earnest undergrads in front of our state Legislature as they read each other Palestinian poetry and chanted in the rain. I’ve not witnessed anyone step in front of a tank, but I did see a young hijabi at a different action respond to an anonymous challenge about the group’s stance on antisemitism—taking the mic, she confidently asserted that antisemitism has no place in any serious freedom movement.

Once, when asked by a young man for a solution to the political crises in her writing, Octavia Butler replied simply, “There isn’t one.” “No answer?” the student asked. “You mean we’re just doomed?” Butler responded, “There’s no single answer that will solve all of our future problems. There’s no magic bullet. Instead, there are thousands of answers—at least. You can be one of them if you choose to be.”

Other answers I have seen: A colleague who runs an international writers’ program, on hearing that the Trump State Department had gutted the program’s funding, immediately began organizing to protect current and future students. When four of Iowa’s international students also lost funding, our community rallied on their behalf; eventually, a federal judge reinstated their visas. Also: a young recovery fellow showing up to the home of a sick friend to fold laundry and wash dishes. My spouse saying goodnight every night to each of our animals and then to a box of our beloved cat’s ashes. My sister-in-law teaching my little nieces how to make zines.

I’m skeptical of anyone selling solutions that sound too big or too certain. Real action needs doing, not selling, so it’s motion I trust. When I stall, it means my aperture’s gotten too wide.

Yesterday my neighbor cooked me chile relleno and told me about painting in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Today I went over to a friend’s house, chased their little kids around the yard, and laid in the grass. When I finish writing this essay, I’ll put some shoes on, call a recovery newcomer, and take my dog to walk in the setting sun. One thing, then the next. For a long, long time.

Kaveh Akbar is the author, most recently, of the novel Martyr! Born in Tehran, he teaches at the University of Iowa.

The New CSA

Kevin Willmott

A little more than 20 years ago, I wrote and directed C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America, a film that told an alternate history in which the South had won the Civil War and shaped the country in its own image.

Making the film alerted me to how Confederate ideology continues to influence American society. Although the South lost the Civil War, it was not until the 1960s that substantial changes occurred in Southern society. Ever since, the United States has been divided between those who accept the results—the enshrinement of equality in the Constitution—and those who don’t. Call them the USA and the CSA. Recently, the two countries have merged into one: The Confederacy has gobbled up the Union.

Lawrence, Kansas, where I live, was, like The Nation, founded by abolitionists. Our historic Massachusetts Street is named after the home state of its earliest settlers, who moved here in the 1850s to keep slavery from spreading to the Western territories. The fighting that followed, in the period known as “Bleeding Kansas,” was an early warning of the nationwide conflict that would come just a few years later.

The city has long celebrated this heritage. My children attended Free State High School. But after the Union victory in the Civil War, Lawrence became segregated, as did much of Kansas. It was, after all, the Topeka Board of Education whose resistance to integration compelled the Supreme Court to intervene in 1954. The free state became segregated because the South won the peace. Now the entire nation is capitulating to the new Confederate States of America.

The old CSA romanticized antebellum Southern life, as in Gone With the Wind. The new CSA also aims to return to an earlier period: the 1950s of Donald Trump’s youth, when white men were dominant, women were homemakers, African Americans held “Black jobs,” LGBTQ+ individuals were in the closet, and Latinos faced deportation.

The new CSA differs from the old in its nationwide presence. Unlike its predecessor, the new CSA ideology is both blatant and subtle. It can attract far-right hate groups as well as growing numbers of African Americans and Latinos.

The Trump administration’s ongoing attack on the federal bureaucracy and wholesale cancellation of government programs; the quest to remove diversity, equity, and inclusion policies; the erasure of Black history; and the reinstatement of Confederate names on military bases are all clear attempts to revive the white supremacy of the CSA. So is the clearly unconstitutional attempt to revoke birthright citizenship, as enshrined in the 14th Amendment, drawn up and ratified by the victors of the Civil War.

Promoting C.S.A. in Memphis shortly after its release, I sat for an interview at a Fox station where the Black anchors were shocked by the film and quietly warned me about showing it in the city. As I left the studio, a receptionist, an older white woman, told me, “The South will rise again.” Indeed, it has.

Kevin Willmott won an Academy Award for cowriting BlacKkKlansman. He has directed numerous feature films.

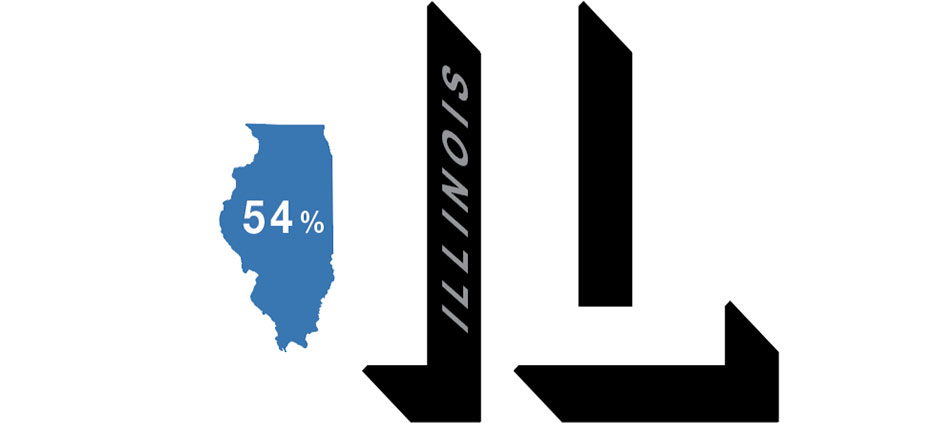

Blood and Bluegrass

Tarence Ray

On the morning of September 7, 2024, Joseph Allen Couch, a former Army Reserve engineer, walked into a gun store in London, Kentucky, and purchased a semiautomatic Cobalt AR-15 with a mounted sight and 1,000 rounds of ammunition. He then took position on a cliff ledge overlooking Interstate 75 and proceeded to spray live rounds into cars passing on the highway, injuring five people. Afterward, Couch disappeared into the surrounding woods and turned the gun on himself, while the state shut down its schools for days in the belief that the shooter was still on the loose.

How did Kentucky come to be the font of such despair and the scene of such carnage? To some extent, it has been this way from the beginning. Just over 250 years ago, settler pioneers like Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton summited the Appalachian crest and began streaming into the land south of the Ohio River Valley, a land sacred to the Shawnee. The Shawnee had obtained promises from the colonial authorities that this would never happen, and yet here were strange white men making strange markings on trees to denote a strange new concept: private property. The Shawnee leader Tecumseh recognized that if the white man was willing to break his promise to never settle the sacred wilderness of Kentucky, he would not stop until he reached the farthest reaches of the continent.

A century later, Kentucky was at the center of another national transformation. Slavery and “slave breeding” had become widespread in this so-called border state—Kentucky, in fact, had over 200,000 slaves by 1850—and yet Abraham Lincoln promised to keep the practice intact in exchange for the state’s loyalty to the Union during the Civil War. This exemption from the Emancipation Proclamation meant that Kentucky became the second-to-last state to adopt a constitution outlawing slavery. In the decades after the war, white supremacist paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorized free Black people. The promise of racial equality was abandoned. It’s not a far leap from there to the 1954 prosecution of the white journalist Carl Braden on trumped-up charges of sedition—for the crime of helping a Black couple, Andrew and Charlotte Wade, buy a house in their Louisville neighborhood—and, more recently, to the murder of Breonna Taylor inside her own home.

In the decades after the Civil War, Kentucky sold off its numerous natural resources to corporate interests, all premised, in some way or other, on vice, alienation, and environmental rot: coal mining, tobacco farming, car manufacturing, horse racing, and bourbon. This made the state vulnerable to “natural” disasters, from floods to fires, sinkholes to tornadoes. But this may, paradoxically, provide the only hope for a brighter future: In the wake of such disasters, one finds efforts toward mutual aid and communal solidarity, the knitting together of new social bonds amid the wreckage of the old. It may be that such bonds are the only hope Kentucky has of reversing the tide of history and becoming sacred once again.

Tarence Ray is a cohost of the podcast Trillbilly Worker’s Party. He lives in Lexington, Kentucky.

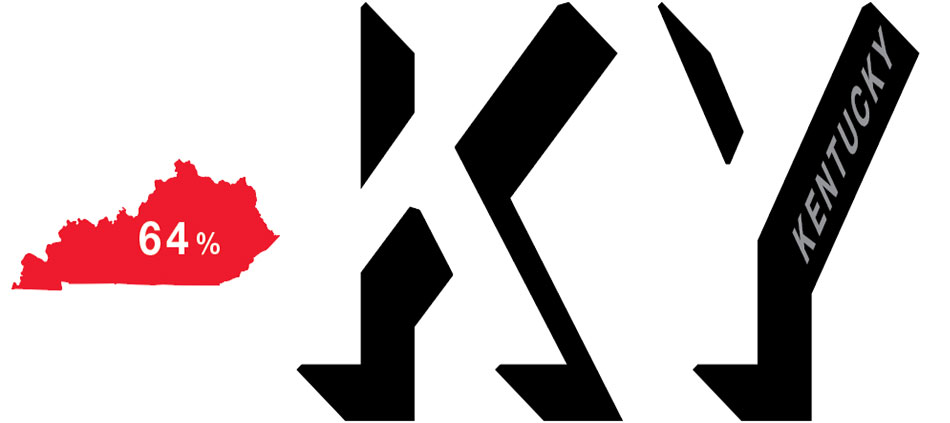

The Big Uneasy

Sarah Jaffe

When people in the United States talk about disunion, they often refer to the Civil War, instinctively pitting the South against the rest of the country. The backward South, the story goes, is still fighting the “War of Northern Aggression.” It is the reservoir of all the nation’s racism.

I see some truth to this. Born in Boston and raised partly in South Carolina, I currently live in Republican-dominated Louisiana, where I can’t get a legal abortion and union membership ranks 44th in the nation. But I also live in New Orleans, where 80 percent of voters backed a workers’ bill of rights in the 2024 election, where union nurses have struck three times for a decent contract in recent months, and where a Palestine-themed Mardi Gras parade has rolled two years in a row.

That workers’ bill of rights had to be carefully written so as not to run afoul of state preemption laws—a problem familiar to people in the South, where Republican-dominated state legislatures ban localities from doing everything from raising the minimum wage to regulating traffic stops by police. Last year, I covered the struggle by organizers in Memphis to pass reforms after the brutal police killing of Tyre Nichols; once the Tennessee Legislature came back into session, it prioritized undoing the local ordinance. Governors and other state politicians have interfered in union elections in Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. Jeff Landry, our Republican governor, sent state troopers to clear homeless encampments in New Orleans even before a former soldier barreled his car down Bourbon Street early on New Year’s Day. After the crackdown, Landry seemed gleeful about his ability to over-police Mardi Gras.

It often feels like those of us in Southern cities are under attack by our own state governments. And yet I also recall this feeling from my time living in Northern cities. New York’s Fight for $15 campaign had to battle then-Governor Andrew Cuomo in order to raise the minimum wage, and Pennsylvania continues to block Philadelphia from enacting gun control.

Indeed, the way a state swings in presidential elections usually depends on whether the major urban areas—strongholds of Black people and immigrants, union members, and LGBTQ people—are populous enough to counterbalance the rest of the state. Georgia, the epitome of the Deep South, has become a key presidential battleground by virtue of Atlanta’s booming population.

When it’s a matter of going to war against their own populations, liberal mayors and city councils have plenty to answer for as well. The movement to stop the construction of Atlanta’s Cop City, a $100-million-plus police training complex, was thwarted by a Democratic mayor and city council. In his time as mayor of Chicago, Rahm Emanuel—fresh from the Obama White House—tried to break the Chicago Teachers Union. When that failed, he closed 50 schools, leaving long-term pain in his wake. And need I repeat the whole sordid Eric Adams saga?

Perhaps we’re not as disunited as we think: In red and blue states alike, we can all relate to seeing the popular will trampled by careerist elected officials, whether at the municipal, state, or federal level. The disunion is coming from inside the house.

Sarah Jaffe is the author of From the Ashes, Work Won’t Love You Back, and Necessary Trouble.

Tangled in Tradition

Kate Christensen

These days, political differences often come down to how you feel about destroying nature for the sake of profit. The gamut runs from can’t-hurt-a-bug bleeding hearts to kill-for-fun, drill-baby-drill psychopaths. Most of us fall somewhere in between. We have to live, after all.

When it comes to conservation, our nation is increasingly divided between two opposing views: the belief that the web of life is sacred and interconnected and must be protected for the good of us all, and the belief that unchecked, unregulated growth is a red-blooded American birthright and that anyone who threatens it is an impediment to progress.

Here in Maine, no enterprise is more symbolic than the lobster industry. The lobsterman is our cultural icon: the hardworking man who chugs out in a boat at dawn and pulls a rugged sustenance from the sea. And there is no more iconic representation of New England’s economic and maritime history than the North Atlantic right whale. Hunted to near-extinction in the 19th century, they rebounded in the 20th century during a period of rising conservationism. But since the deregulations of the Reagan era, when environmental protection became politicized, the pendulum has swung hard right, even in the face of looming catastrophe. Today, right whales are once again gravely endangered—as of last count, there are fewer than 370 of them left.

Entanglement in fishing gear and strikes from ships, often lobster-fishing vessels, are the primary threats to the whales. In the Gulf of Maine, the whales’ migratory path takes them through a thicket of 400,000 lobster-fishing lines, vertical buoy lines that run from the surface down to traps on the ocean floor. When whales become entangled, they critically injure themselves or starve to death. Because of rising ocean temperatures, the lobster population in the Gulf of Maine has exploded in recent years as it’s plummeted in southern New England. But scientists are projecting an imminent decline in the gulf as well due to the lobsters’ ongoing northward migration, since the Gulf of Maine is the fastest-warming body of water on Earth.

In the face of their own looming obsolescence, and despite the damage their gear does to these endangered whales, the lobstermen have been doubling down. Instead of pivoting as an industry to oyster or kelp farming, they’re fighting for their right to keep catching lobsters the same old way. Lobster harvests in the Gulf of Maine reached an all-time high in 2021 but have been declining ever since. In 2022, a major ocean conservancy group put Maine lobsters on its do-not-eat “red list” to call attention to the plight of the whales, prompting the lobstermen to sue for defamation. Industry spokespeople claim that ropeless fishing, which uses acoustic modems and remote-deployed trap recovery methods, would cost a prohibitive $375,000 for a lobsterman fishing a full allocation of traps in eight-trap trawls. There is no practical solution at present beyond the lobstermen voluntarily suspending fishing during whale migration.

Meanwhile, whales keep dying from getting entangled in lobster-fishing lines, and the industry evidently intends to keep pulling lobsters out of the Gulf of Maine until they’re all gone. This is the only way of life the lobstermen know. Their identities are inextricably connected to it.

This is human nature, the American way. The tension between conservation and exploitation has always been tricky to balance. In the struggle between lobstermen and the right whale, there are no winners. And as Maine goes, so goes the nation.

Kate Christensen is the author of two memoirs and 11 novels, most recently Good Company, forthcoming in the summer of 2026.

Democracy on Trial

Madison Smartt Bell

For me, as for many, the ultimate question is whether the United States will become an autocracy or remain a nation of laws. In the latter case, the object of the game is to discover and enact what citizens actually want; to that end, laws are created by the national legislature, implemented by the executive, and tested by the courts by reference to the US Constitution, a document that has been revised from time to time, usually for the better. The risk now is that, for the first time in our history, it may be disregarded—or even jettisoned altogether. That would make the United States one of the most dangerous autocracies in the world, alongside Russia and China.

Since 2016, most legislators on the right have cravenly capitulated to executive overreach. Preemptive compliance happens in the futile hope that caving in advance of absolute compulsion may protect a group from being noticed or harmed.

The despotic intention of the executive no longer bothers to mask itself. If the legislature continues to do nothing to oppose it, the next recourse is the courts. So far, the judiciary has mostly held up, likely because anyone who has made a career in the legal profession believes very firmly in the rule of law. There may be exceptions, including a couple on the Supreme Court—although at the time of this writing, it seems the majority of the highest court does follow the rule of law.

The next test will be whether the executive will simply flout court orders, a thing some have already declared it will do, and which is already beginning to happen.

After that, the test will be whether the midterm elections in 2026 will actually be free and fair—which may not happen without struggle.

The next test will be whether the military, which has supported the rule of law up to now, can be corrupted from the top down, something which has certainly happened elsewhere. That possibility takes us to a very dark place. As a Southerner, I have an atavistic memory of what it’s like to lose a civil war, and the conditions for another one have been present for a long time. We have the most heavily armed civilian population on the planet, and for now, the arms are mostly in the hands of the right wing.

The Calvert family founded what became the state of Maryland on a principle of tolerance—religious tolerance at first, because the Calverts were closet Catholics in an age of compulsory Anglicanism. But tolerance of other kinds of difference expanded to become part of both the state and the national culture, including the political culture—though not without being aggressively challenged, time and again. In this area we have lately been failing, as much on the left as on the right. The left has been wrong in dismissing its opponents as ignorant, backward, deplorable.

To practice real tolerance, one must try to understand the motives of those who think and act differently, which in turn requires the difficult operation of entering into the point of view of the other. One of the appeals of autocracy is that it allows such difficulties to be evaded, because difference can simply be stamped out or driven underground.

Madison Smartt Bell is the author of numerous books, most recently The Witch of Matongé.

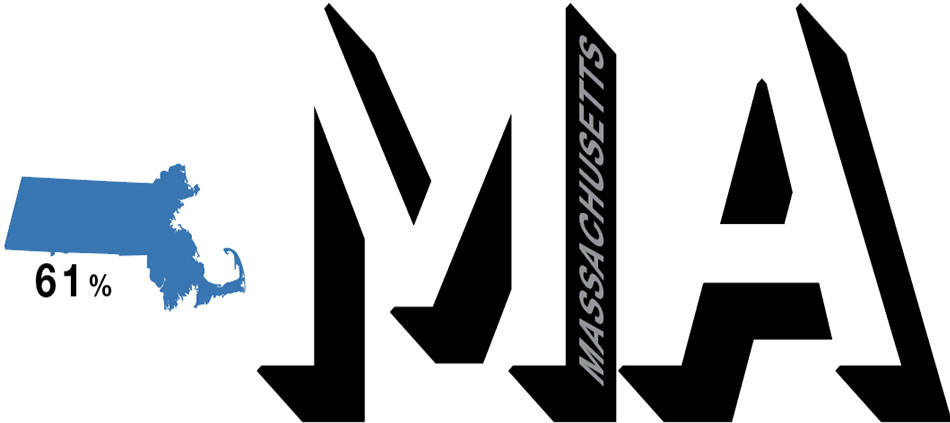

Our Oldest Rift

George Scialabba

Massachusetts and South Carolina have a troubled history. Before the Civil War, Massachusetts was probably the most vociferously anti-slavery state, and South Carolina probably the most ardently pro-slavery. John C. Calhoun, slavery’s most implacable and articulate defender, was a South Carolinian; the best-known abolitionist journal, William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, was published in Boston. Massachusetts insisted on tariffs to protect its manufacturers; South Carolina bitterly resented the effect of those tariffs on its agricultural exports.

On May 20, 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner delivered a scorching anti-slavery speech that contained particularly harsh criticism of South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler. Two days later, Butler’s younger cousin, South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks, approached the elderly Sumner in the chamber and beat him senseless with a cane. Sumner was severely injured and was absent from the Senate for three years, but Brooks’s action was popular in South Carolina: Hundreds of people sent him canes to replace the one he had broken in his assault on Sumner.

When the war came, Massachusetts Governor John Andrew agitated for an African American regiment. President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton were reluctant, but Andrew persisted. Finally, the regiment was formed; to train and lead it, Andrew tapped 25-year-old Robert Gould Shaw, the son of a notable Massachusetts abolitionist. At first, the regiment was kept out of combat and confined to support services. It was eventually allowed to spearhead the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina. The regiment took heavy casualties, and one of the first was Shaw. It was customary on both sides to return the bodies of officers to their families for burial. The Confederates made an exception for Shaw, whom they despised for leading Black troops. He was thrown with his soldiers into a mass grave. His abolitionist father called that the highest honor he could have wished for his son.

Today, Massachusetts and South Carolina are as far apart as ever. This time there is no prospect of either armed conflict or secession—the plutocracy will not allow it. An independent North and Pacific West would likely evolve into a social democracy, as the whole country might well have done if not for the South’s stubborn resistance to civic equality, organized labor, and the welfare state. The plutocracy is wholly dedicated to preventing any evolution toward social democracy, or even a return to New Deal liberalism.

What could begin to undermine this deep-rooted sectional mistrust? Short of winning back control of all three branches of government, which may take a while, perhaps a little cultural exchange would help. What if every Massachusetts high school student had to spend a year in South Carolina, and vice versa? It undoubtedly wouldn’t turn a whole generation of South Carolina’s youth into wild-eyed radicals or Massachusetts’s youth into pigheaded reactionaries. But they might be slower to reach for that cane.

George Scialabba’s most recent book is Only a Voice: Essays.

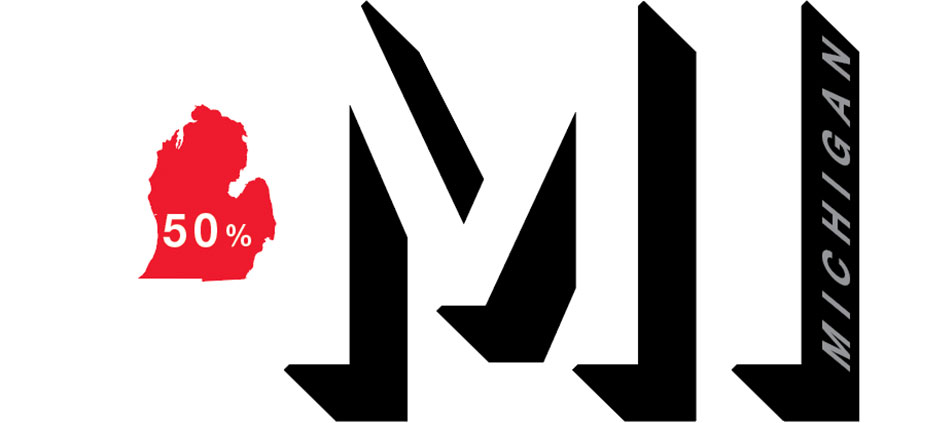

How Water Divides Us

Anna Clark

In times of groundlessness, I come back to the water. In Michigan, it can’t be helped.

My native state is split across two peninsulas stitched together by a five-mile-long suspension bridge and bordered by four of the largest lakes in the world. I’m the type that boasts to oceanside friends of the majesty of the Great Lakes: their frigid depths; their thousands of miles of shoreline; their store of nearly all the fresh water in the United States. Poured over the lower 48 states, it would settle at a depth of more than nine feet. Even well beyond this inland coast, Michigan’s abundance of lakes, streams, and rivers means you’re never more than six miles from a natural body of water.

So goes my Middle West patriotism. It’s a common sort, across all corners of this swingiest of states. But water is revelatory. It forces us to be honest. And the truth is, our water is a weapon as much as it is our shared wealth.

It wasn’t long before The Nation’s founding that the river between Detroit and Ontario—a final crossing on the Underground Railroad—divided people between enslavement and freedom. “Thanks be to Heaven that I have got here at last,” wrote one who got free. “On yonder side of Detroit river, I was recognized as property; but on this side I am on free soil.”

Nearly 200 years later, the water still wrenches us apart. I grew up at the outlet of the St. Joseph River into Lake Michigan. All my life, and long before, that river has been a shorthand for the divide between two very different towns: St. Joseph (largely white, well-off) and Benton Harbor (largely Black, poor). For many, the river was itself a source of fear—and crossing it was out of the question. I may have grown up working-class, but living in St. Joe privileged me with vastly different prospects than those of a kid in a similar family just a mile or so north. This country was built on the violent foundation of “separate but equal,” and here, in towns I love, is one more place where it is perpetuated still.

Then, too, Michigan is home to the Flint water crisis. It began in 2014, when the choices made by those who held power over a poor city of nearly 100,000 people turned their drinking water toxic, especially with lead and deadly Legionella bacteria.

In 2016, when I was working on a book about the water crisis, a poet in Flint opened her home to me. The city was still reckoning with the fallout. The poet’s ringing question haunts me: “Can water be made holy again?”

I find my words meandering like the ghost streams of Detroit, buried long ago under the city streets. But this is the point: Michigan’s waters demonstrate the cause and effect of our choices in an uncomfortably literal way. Our past flows into our present. We must meet it to meet each other. There is no other way.

Anna Clark is a Detroit-based investigative journalist with ProPublica. She teaches creative nonfiction at Alma College in its MFA program.

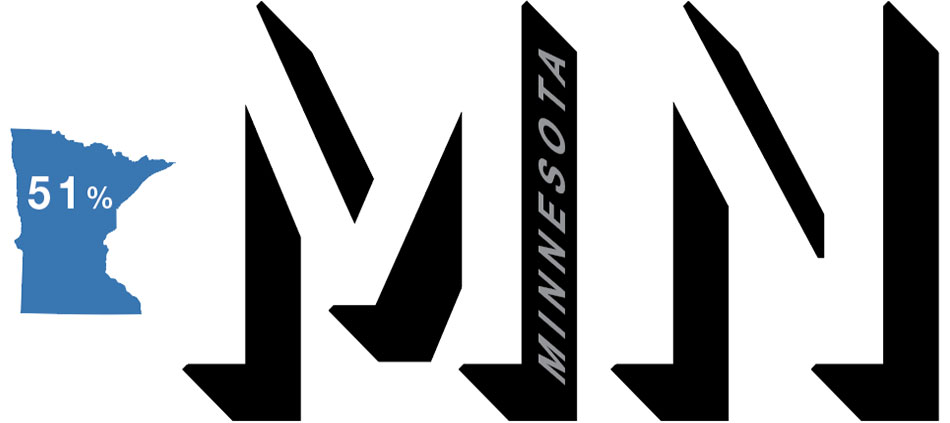

Learn From the Land

David Treuer

My homelands, my Ojibwe tribal homelands, are an intimate place, somewhat devoid of grandeur, but to me and my kin indescribably beautiful. These homelands are studded with lakes. Some, like Lake Superior, Lake Mille Lacs, Leech Lake, and Red Lake, are so vast they can’t be seen across. Others, mere dips in the land, are so small they have no name at all. But all remind me of Joseph Conrad’s description of the ocean, which “seemed to pretend there was nothing the matter with the world.”

But, of course, there was. And here in the western Great Lakes region, there is: the series of treaties we, the Dakota, and other tribes signed with the US government between 1805 and 1867, which resulted in the state of Minnesota imposing its sovereignty like a poorly folded blanket over the corpse of our great Native Nations—the most premature of burials.

It began even before statehood in 1858 but accelerated with European settlement. Swamps and bogs were filled in to make way for plowed fields. Forests were cut down. Over the past 150 years, Minnesota has lost roughly half of its wetlands and half its forests. Prairies have fared even worse: Some 19 million acres have been reduced to around 58,000. Bison and elk went extinct east of the Mississippi. All that remains of the original forests are 144 acres of old-growth red and white pine just north of my reservation, known as the “Lost Forty.”

But despite those losses, our Nations did not die out. We survived and grew. We have remained alive, profoundly so, enough to curb the appetites and shape the behavior of our younger civic brother, the state of Minnesota. We have welcomed our new Somali and Hmong relatives. We shape our governments and keep them true to their ideals.

In 2023, the Minnesota Legislature passed—and Governor Tim Walz signed—new laws guaranteeing 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave, free public and college tuition for lower-income Minnesotans, a new child tax credit, free lunches for all public school students, driver’s licenses for all residents regardless of immigration status, stronger unionization, the restoration of voting rights for convicted felons, protections for abortion rights, and a “trans refuge” law that protects transgender children traveling to Minnesota to receive gender-affirming care from states that would punish them. Legislation also passed that set 2040 as the goal for Minnesota’s electricity to be carbon-free.

Back in the treaty days, our leaders would often refer to themselves as children and to the United States or the president as the “Great White Father.” This was a rhetorical strategy used to placate an insecure but powerful opponent. The truth is now clear: Our civilizations are older, we’ve been here longer, we have been the “father,” and Minnesota, all the other states, and the Union itself are our children.

At least compared with its neighbors—Iowa, South Dakota, and North Dakota, where the seeds of liberalism have largely died back or never took root—Minnesota remains committed to all three words in the official name of its dominant political party: “Democratic,” “Farmer,” and “Labor.” The state is perhaps not unlike the Lost Forty: grown up, somewhat alone, but ready to reseed the political land around it with something that will actually grow.

David Treuer is Ojibwe from the Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota. His latest book is The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America From 1890 to the Present.

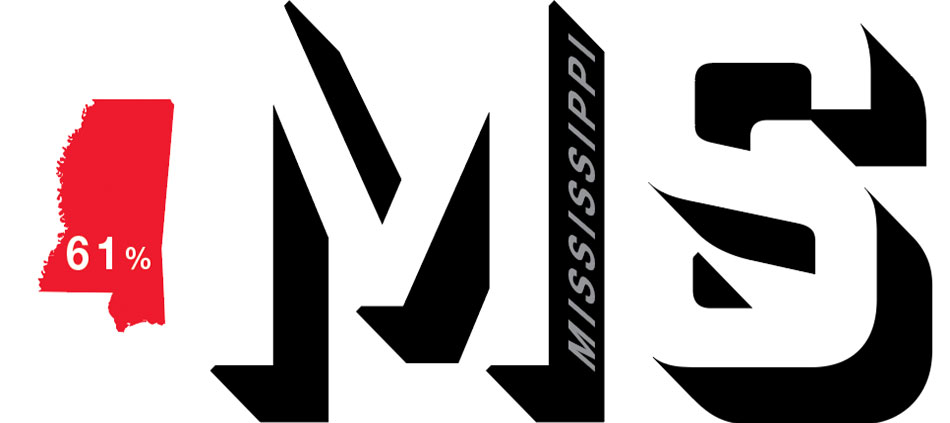

Freedom Fight, Redux

Makani Themba

In the late 1990s, a group of anti-poverty activists in Idaho told me that one of their most compelling arguments was to tell legislators that their state was in danger of becoming Mississippi.

Nobody wanted that.