Spiders taught scientists how to make unsinkable metal

Researchers mimicked the air-trapping tricks of diving bell spiders to create aluminum that stays afloat—even when punctured

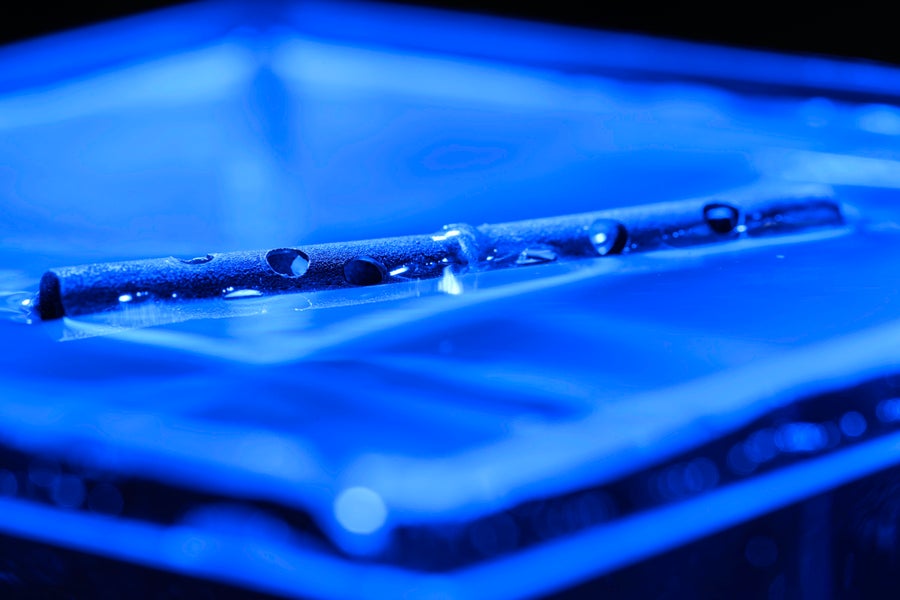

“Unsinkable” metal tube floats in distilled water at the lab of University of Rochester professor Chunlei Guo January 9, 2026.

J. Adam Fenster/University of Rochester

Toss a coin into a fountain, and you know what will happen. Being denser than water, the metal sinks—ask any child. But new research has challenged centuries of certainty.

A team at the University of Rochester has etched aluminum tubes so that they won’t sink, even when damaged—a trick the scientists borrowed from spiders.

“You can poke big holes in them,” said Chunlei Guo, a professor of optics and physics at the University of Rochester and senior author of the research, in a press release. “We showed that even if you severely damage the tubes with as many holes as you can punch, they still float.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Many things in our lives repel water—examples include cooking oil, a rain jacket or a rubber glove. Scientists call this property hydrophobicity—from the Greek for “water fear”—but the secret to the metal tubes’ buoyancy lies in superhydrophobicity.

Guo’s team uses lasers to carve microscopic valleys into the aluminum that capture air: picture corduroy fabric shrunk down until it requires an electron microscope to see the ridges.

According to the press release, “the mechanism is similar to how diving bell spiders trap an air bubble to stay buoyant underwater.” The spiders live almost entirely underwater but still need to breathe. Their solution is to carry their own oxygen supply. Fine hairs covering their bodies trap air bubbles against their skin.

The metal tubes mimic those fine hairs, trapping their own air bubbles. Normally water would spread along the inside walls and push the air out. But when it hits the superhydrophobic texture, it bounces away. Surface tension—the same property that causes water to bead on a waxed car hood—prevents the water from entering the tube. As a result, the air stays inside, and the tubes remain buoyant.

The study, published on January 27, 2026, in Advanced Functional Materials, builds on Guo’s earlier work designing unsinkable metals. In 2019 his lab demonstrated the concept using laser-etched disks, but in turbulent water, the disks tipped, and the air escaped.

The new tubes solve that problem with an internal divider at the middle of the tube that helps trap the air in a confined chamber. “Even if you push it vertically into the water, the bubble of air remains trapped inside and the tube retains its floating ability,” Guo said in the same statement. The team tested the tubes in rough conditions for weeks and “found no degradation to their buoyancy,” he reported.

“Unsinkable” metal tube damaged with holes floats in distilled water at the lab of University of Rochester professor Chunlei Guo January 9, 2026.

J. Adam Fenster / University of Rochester

In nature, superhydrophobicity isn’t a new trick. The eyes of mosquitoes have water-repellent nanostructures that keep them clear, for example. And fire ants use their waxy, water-repellent coating and textured exoskeletons to trap air; during floods, thousands cling together to make buoyant, living rafts that can survive 12 days and possibly longer.

As for humans, this isn’t our first attempt at floating metal. In 2015 researchers at New York University embedded hollow silicon carbide spheres in a magnesium alloy to create a metal matrix composite lighter than water.

But the implications of Guo’s work go beyond the laboratory. Linked tubes could create weight-bearing rafts or ships. Engineers might be closing in on the dream of ships that stay afloat even as water pours into their hulls. One surprising application involves energy: Guo’s team demonstrated that rafts made of the tubes could harvest waves to generate electricity.

The tubes are currently nearly half a meter long, but Guo sees no barrier to increasing their size. The lasers are now seven times more powerful than they were in 2019, when Guo first attempted laser-etched metal disks. “The technology,” he said in the same statement, “could be easily scaled to larger sizes.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.