When astronomers glimpsed the first images from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in July 2022, they saw the kind of universe most of them have come to expect. There were dazzling blue bursts of light, glowing trails of stardust, curtains of gas backlit by the birth of stars.

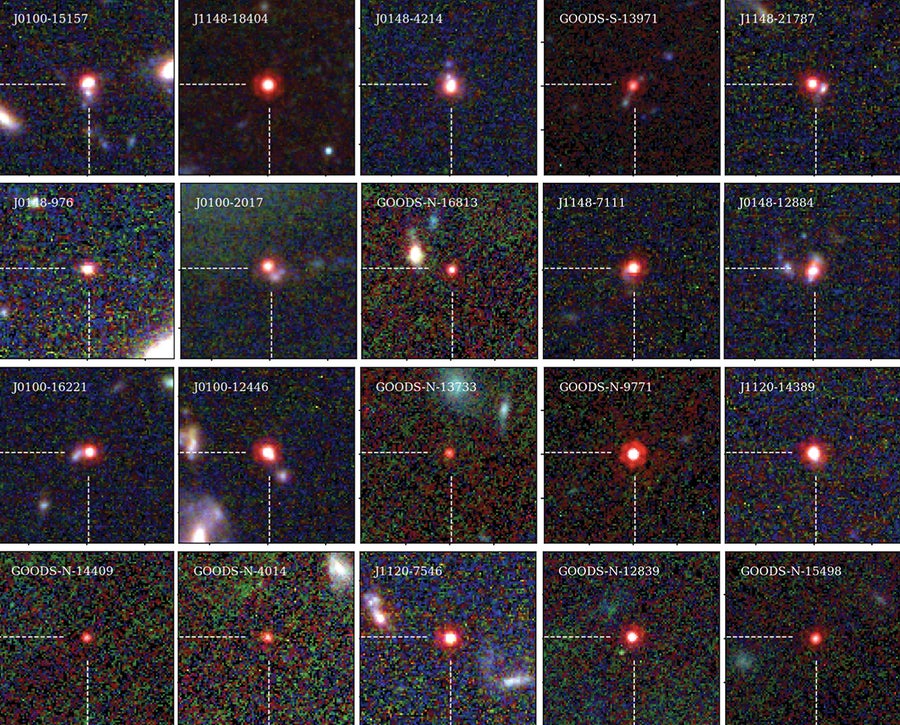

But things got weird very quickly. Almost every new image showed mysterious, tiny red points. The spots were extremely compact, very bright and distinctly red. There were so many of them. Everywhere JWST looked, the telescope found at least one specimen of what are now commonly called Little Red Dots (LRDs).

Astronomers quickly dated the dots to about 600 million years after the big bang, which means their light traveled almost the entire lifetime of the universe before arriving in JWST’s honeycomblike hexagonal mirrors. The dots were everywhere, until they were nowhere; about 1.5 billion years after the big bang, they mostly disappear.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The age, size and sheer number of the Little Red Dots all point to something new, something that JWST is uniquely capable of seeing. “They are in every single image the telescope takes,” says Massachusetts Institute of Technology astrophysicist Rohan Naidu. “We have to find out about them if we want to tell a complete story about the early universe.”

At first, astrophysicists coalesced around a few theories to explain LRDs, each of which has implications for the evolution of the universe. Little Red Dots might be compact galaxies with brightly belching black holes at their centers. They could represent a never-before-seen stage of the black hole life cycle. They could be dusty starburst galaxies, exploding with new stellar populations like so many popcorn kernels encountering hot oil.

If Little Red Dots are indeed supermassive black holes, their prevalence could help us understand the nature of these weird perversions of gravity. The dots might reveal how black holes evolve and grow so fast and even how galaxy clusters develop. They could help theorists study direct-collapse black holes, a relatively new concept in which a black hole forms not from a dead star’s carcass but in a sudden collapse of gas, much the way a star ignites.

But more recently, many astronomers are favoring the kind of conclusion that drives entire careers in science. The Little Red Dots may be a totally new class of cosmic object. The latest theories suggest they could be something called quasi-stars or black hole stars, a concept originally predicted 20 years ago. Although some experts remain skeptical, the idea is quickly gaining traction.

And if they do represent some entirely new feature of the universe, they stand to change our entire conception of the cosmos, just as the 1950s and 1960s discovery of quasars—hungry black holes in the centers of galaxies—revolutionized our understanding of galaxy evolution.

Several astronomers say they are having a hard time keeping up with the literature on LRDs because groups from dozens of countries are sharing new research papers almost every day. “I don’t think there is any consensus yet,” says M.I.T. astrophysicist Anna-Christina Eilers. “And even if there are theories we like, there are a million open questions.” Dale Kocevski, an astrophysicist at Colby College who has been scrutinizing LRDs since they started showing up, was somewhat more sanguine. “I’m sure in a year or two we will probably figure out what’s going on,” he says. For now the Little Red Dots hide in disguises no one recognizes—yet.

The redness of the Little Red Dots is an important signal about their identity, and they seem to be red for at least two reasons. For one, the dots are very old, and old things appear red because their light has stretched along with the expanding universe during the time it took to travel all the way to us. This stretching of light into longer wavelengths is known as redshift.

But astronomers have realized that Little Red Dots are also inherently red: not only has their light been stretched, but they also must be full of dust that blocks other wavelengths of light. One of the first scientific papers on the dots, published in March 2024, noted that they were abundant and “seem to be heavily enshrouded in dust, presenting as red point sources amidst blue star-forming clumps.” The authors, led by Jorryt Matthee of the Institute of Science and Technology Austria, gave the objects their friendly, familiar-sounding name.

Little Red Dots are everywhere in JWST images because the telescope is designed to see red light, especially the mid-infrared wavelengths these objects emit. The Hubble Space Telescope can’t see that light, and previous infrared observatories such as the Spitzer Space Telescope didn’t have JWST’s power. Two instruments on JWST, the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), are the Little Red Dot workhorses, unveiling hundreds of the ruddy specks.

One key aspect of Little Red Dots requires a bit of chemistry to understand. The specks are characterized by a strong “Balmer break,” a dip in the light they emit below a certain wavelength. This wavelength represents the amount of energy it takes to kick an electron out of a specific orbital in a hydrogen atom. When an object gives out less light below this wavelength than above it, astronomers can surmise that the energetic light is being absorbed by hydrogen electrons, which suggests there must be a source of these high-energy photons. Observing a Balmer break in a galaxy usually means it’s full of young, hot stars. And the LRDs have a telltale Balmer break in their spectra.

Initially astronomers thought this meant the LRDs were galaxies producing tons of hot stars—up to tens of billions of suns. These galaxies would also be very efficient at producing dust, which would explain why they look so red instead of brilliant, baby-star blue. But there was a problem with this theory. It’s normal for a galaxy the age of, say, the Milky Way to have produced billions of stars, but that’s all but impossible for a galaxy that has been around for only an eyeblink of cosmic time, as the Little Red Dots have. What’s more, the dots are too small to contain billions of stars. Based on their light signatures, packing that many stars into an object the size of an LRD would be equivalent to squeezing several hundred thousand more suns between here and the next-nearest star system, Proxima Centauri. This would be hard to square with current cosmological theories for the early universe, not to mention theories for how stars form and interact.

Since it turned on, the James Webb Space Telescope has revealed dozens of mysterious red blobs in space. The so-called Little Red Dots start to appear around 600 million years after the big bang and seem to disappear by around 1.5 billion years after the big bang.

Images isolated from “Little Red Dots: An Abundant Population of Faint Active Galactic Nuclei at z ~ 5 Revealed by the EIGER and FRESCO JWST Surveys,” by Jorryt Matthee et al., in the Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 963; March 10, 2024 (CC BY 4.0)

As astronomers observed more Little Red Dots throughout 2024, they discovered that the pinpricks were spinning rapidly—evidence they could instead be small galaxies anchored by roiling, incandescent black holes, known as active galactic nuclei. But this theory also has issues because the LRDs show no evidence of x-ray emission, which is common for black holes, or of the kind of light that we know surrounds other dust-reddened active galactic nuclei. And mass is again a problem: the black holes would need to be huge compared with the tiny galaxies that housed them, some of which would be about 100 times smaller than the modern Milky Way.

By the end of 2025 new observations had shown that not all LRDs were as dense as originally thought. In a couple of cases, they were not actually as far away as astronomers thought, either. In fact, one key study argued that the Balmer break, that line indicating young, hot stars, could be made by other things, too.

Many questions remained. Are the Little Red Dots indeed dusty starbursts? Are they shrouded active galactic nuclei? Are they something new instead? Or, as at least a few astronomers have suggested, are they some combination of all of the above? Any of these answers could have cosmic implications. “It’s this big mystery that is in every single image we take, so let’s figure it out,” Naidu says.

As astronomers gathered more examples of Little Red Dots, many became convinced that black holes must be involved somehow. “Even if they are extremely compact star-forming galaxies, stellar collisions in them would naturally lead to formation of massive black holes,” says Muhammad Latif, an astrophysicist at United Arab Emirates University.

In widely cited research, Kohei Inayoshi, an astrophysicist at the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at Peking University, calculated that a cloud of gas in front of a black hole would produce a signature similar to that of the LRD light. “That kind of killed the idea that these are massive galaxies,” Kocevski says.

In February 2023 Anna de Graaff of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian teamed up with colleagues to propose a new LRD-hunting program called RUBIES, for “Red Unknowns: Bright Infrared Extragalactic Survey.” They used nearly 60 hours of JWST time to observe 4,500 distant galaxies and found about 40 Little Red Dots. They found a doozy nicknamed the Cliff, which the team coined after the sharp Balmer break in the spectrum of light it emitted 11.9 billion years ago.

De Graaff’s group produced a graph of this LRD’s light showing nearly zero ultraviolet light and a sudden spike for longer, less energetic wavelengths of light. This sharp transition in light emission is not something a typical galaxy can pull off, de Graaff says. And no black holes in the nearby universe can do it, either. Rather the strange cliff in light emission suggests that the Little Red Dot must be superenergetic, like a black hole, but it also must be swaddled in a cocoon of warm, dense gas—just like the atmosphere of a star.

These developments got Mitch Begelman’s attention. An astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder, Begelman had predicted just such a structure in a theoretical paper in 2006. What he called “quasi-stars” could form within hot clouds of gas, which would quickly collapse to ignite a gargantuan star that undergoes nuclear fusion for a short time. Within a few million years, after its supply of hydrogen burns out, the core contracts, implodes and forms a black hole.

“To our surprise, when we tried to follow this theory, we found the implosion would not release enough energy to blow the envelope away,” Begelman recalls. “You would end up with a black hole and with 99 percent of the stellar envelope left. The black hole would be in the center, so it is releasing energy, but not through nuclear fusion”—in other words, it’s shining because the black hole is gobbling gas, instead of a stellar furnace powering the glow. His concept predicts that quasi-stars would be humongous, corresponding to about a million times the mass of the sun. And so far the LRDs seem to fit the bill. “They don’t look like they are made of stars,” Begelman says. But they are not ordinary black holes, either.

Last July, Naidu, de Graaff and their colleagues argued that LRDs are objects very much like Begelman’s quasi-stars: not quite star and not quite black hole but a bit like both. Naidu and de Graaff have been calling such objects “black hole stars,” which would be gigantic, bright balls of gas lit up by the energy of a black hole at their heart rather than by nuclear fusion.

“I think this is definitely, by far, the most exciting thing to come out of JWST,” Naidu says. “I am fully working on this and setting everything else aside. It’s very rare in astronomy that you come across an entirely new class of object, and I am pretty convinced that is the case here.”

His and de Graaff’s model explains several peculiarities of Little Red Dots, including their apparent lack of x-ray emission, otherwise a black hole calling card. “If you start thinking about them now as essentially this enormous star that has a black hole at its center, things start falling into place,” he says. “You understand a whole gamut of really peculiar features.”

De Graaff says the Cliff is probably a black hole star, and a couple of other LRDs are also very likely to be in the same class. But debate persists about whether all the mysterious objects fit into that category, she says. “If you ask a random astronomer on the street, I don’t think they would say every LRD is a black hole star,” she says. “But if you ask my team, yes.”

One question is whether black hole stars represent an early phase of black holes in the universe—before they lose their red-dimmed outer envelopes of gas. If Little Red Dots do represent some strange stage of the black hole lifespan, they could help solve a mystery about how the large ones formed.

Black holes were predicted by Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity, and astrophysicists have imagined that they are born after giant stars implode and cave inward. The cosmos is chockablock with black holes that seem to have originated this way. But supermassive black holes, the ones that churn at the heart of nearly every galaxy and weigh hundreds of millions or billions of suns, are harder to understand. They had to grow large enough quickly enough to shape the galaxies that surround them, but most models for black hole growth can’t make behemoth objects that fast.

Some theorists have argued for a new model called direct-collapse black holes, in which an enormous black hole “seed” grows from a dense cloud of gas. Instead of a star igniting in the cloud, an ultradense, gravitationally gargantuan black hole is born instead.

Begelman thinks black hole stars might represent a version of this theory. “Theoretically, we can understand the conditions that would lead to the gas collecting and then collapsing immediately into a black hole,” he says. “But my personal suspicion is that it is very difficult to avoid the intervening stage of having something like a supermassive star.”

Little Red Dots could represent a variety of objects at different ages, revealing different phases of existence.

And whether or not the direct-collapse idea is right, LRDs could be the precursors of the supermassive black holes that form the hearts of modern galaxies. Inayoshi, who theorized that the dots could be black holes with gas envelopes surrounding them, suggests they are just a phase of black hole growth, possibly the first time newborn black holes begin gobbling up mass. Little Red Dots would therefore be black hole baby pictures.

In a separate paper submitted last December, Inayoshi and his colleagues argue that the black hole envelope model, or black hole stars, can explain the Little Red Dots’ strange light features and their apparent densities. If this paradigm is right, then the LRDs are a short-lived, efficient growth phase in the early lives of supermassive black holes.

This could explain the huge amount of dots in the early universe, as well as where they are now, Begelman says. “They become supermassive black holes, and there is one per modern galaxy, so you need a lot of them,” he says.

As the theorists have been sharing these ideas, observers have come back with evidence that strengthens the case—and challenges the prevailing wisdom. A team co-led by Pierluigi Rinaldi of the Space Telescope Science Institute, for instance, reported another oddball last November, a galaxy called Virgil that seems to have a reddish, supermassive black hole at its heart.

When viewed in visible light and even bright-blue ultraviolet, Virgil is a normal-seeming galaxy, seen about 800 million years after the big bang. But when JWST’s MIRI instrument takes a look, the galaxy’s light suggests the presence of a giant black hole that is seemingly too big for Virgil to hold.

The discovery suggests a new path for black hole and galaxy growth. Before JWST, astronomers had assumed that galaxies formed first and ultimately came to host supermassive black holes—whether seeded by direct collapse or otherwise—in their hearts. But now it looks like black holes might grow first.

This finding could have implications for the quest to understand the first light of the universe. Astronomers still struggle to explain the so-called cosmic dawn, a turning point sometime between 50 million and 100 million years after the big bang when the first stars ignited. Somehow their sparkling ultraviolet light recharged the neutral gas that pervaded the universe, preventing free hydrogen nuclei from combining with electrons to make neutral atoms. This process is called the epoch of reionization. But astronomers are not sure how it happened. Did the ionizing light come from young stars? Or did it come from gluttonous black holes stealing the warm wind and superheating gas?

The story of Virgil, and maybe other LRDs, suggests astronomers have been missing something big. Dust-obscured black holes seem to have played a bigger role in reionization than anyone thought—we just could not see them until now, because they shine in red light that only JWST is powerful enough to finally observe. Many more such giants might be out there, unseen until JWST takes more long, deep looks, Rinaldi says. “That is blowing my mind,” he says. “Maybe we are missing a very important piece of the puzzle because of the fact that we don’t have enough deep-field data.”

Meanwhile the search continues for more Little Red Dots. Last July astronomers claimed a discovery of three Little Red Dots about a billion light-years from Earth. These closer dots, which are inherently much younger, suggest LRDs can crop up later in the universe, too.

Then, last December, astronomers used the Very Large Array to detect one in radio wavelengths, also fairly local. And Kocevski says astronomers are sifting through existing datasets, such as observations from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, to uncover even more nearby specks.

In one unusual case, announced last December, another galaxy between a Little Red Dot and us helped astronomers see the object through various snapshots of time. This LRD’s light was magnified four separate times by a galaxy positioned in front of it from our perspective. The effect, called gravitational lensing, is another consequence of Einstein’s theory of gravity. The Little Red Dot in question seemed to vary over 130 years, according to the researchers, led by Zijian Zhang of Peking University. More deep observations are necessary to figure out how LRDs evolve over time, says Rinaldi, who was not involved in that work. “The more data you get across different epochs, the more you can time travel,” he says.

Finding Little Red Dots at different distances and times will help astronomers understand how they evolve and whether they do represent black hole infancy, a black hole star structure, or some other phenomena.

Perhaps Little Red Dots formed within very slowly spinning halos of dark matter, as one example. Invisible dark matter sculpts the universe, surrounding galaxies and clusters of galaxies like a halo. Dark matter halos spin, which astronomers can observe by studying gas flows. In a paper submitted last April, Fabio Pacucci of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and his colleagues argue that LRDs could have formed in dark matter halos that spin very slowly, which would naturally create very compact galaxies. In a recent example, a Little Red Dot is surrounded by eight nearby galaxies and embedded in a dark matter blob. Eventually such an LRD could evolve into a quasar, the most luminous galaxy type, which is usually found inside a dark matter halo.

Another theory holds that LRDs could represent a variety of objects at different ages, revealing different phases of existence. Rinaldi, Karina Caputi of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and their colleagues say that different LRDs have different characteristics and may be different things entirely. In a paper published last October, the team argues that some LRDs hold the telltale evidence of active black holes, showing gas streaming at thousands of kilometers per second. But other LRDs seem to host star factories instead. That sharp break in their light absorption ability, so typical of LRDs, could defy a simple answer, they say. “I am not totally convinced they are the same kind of object,” Caputi says.

Although most astronomers are convinced the Little Red Dots are black holes of some kind—infant, gas-shrouded, direct collapse, or stellar—many questions remain. Dozens of research groups submitted proposals last year for the next cycle of JWST observations. The team of astronomers that divvies up every minute of the telescope’s time has been working through those applications and will announce project selections soon.

A top priority is figuring out how massive the Little Red Dots are, which will help scientists determine what types of objects they could be, and whether they might be many different things at once. Current methods for measuring black holes fail for the dots, so new strategies and theories are necessary. M.I.T.’s Naidu aims to produce a life-cycle chart for black hole stars, much like the fundamental Hertzsprung-Russell diagram that plots the life stages of stars according to their brightness and surface temperature. “The fate and the destiny of all stars is encoded in a few parameters: how hot they are, how bright they are and what their surface parameters are. These are the kind of things we have to measure for the LRDs,” Naidu says. Someday, he hopes, these oddball red spots will be understood just as well.