ChatGPT Is Changing the Words We Use in Conversation

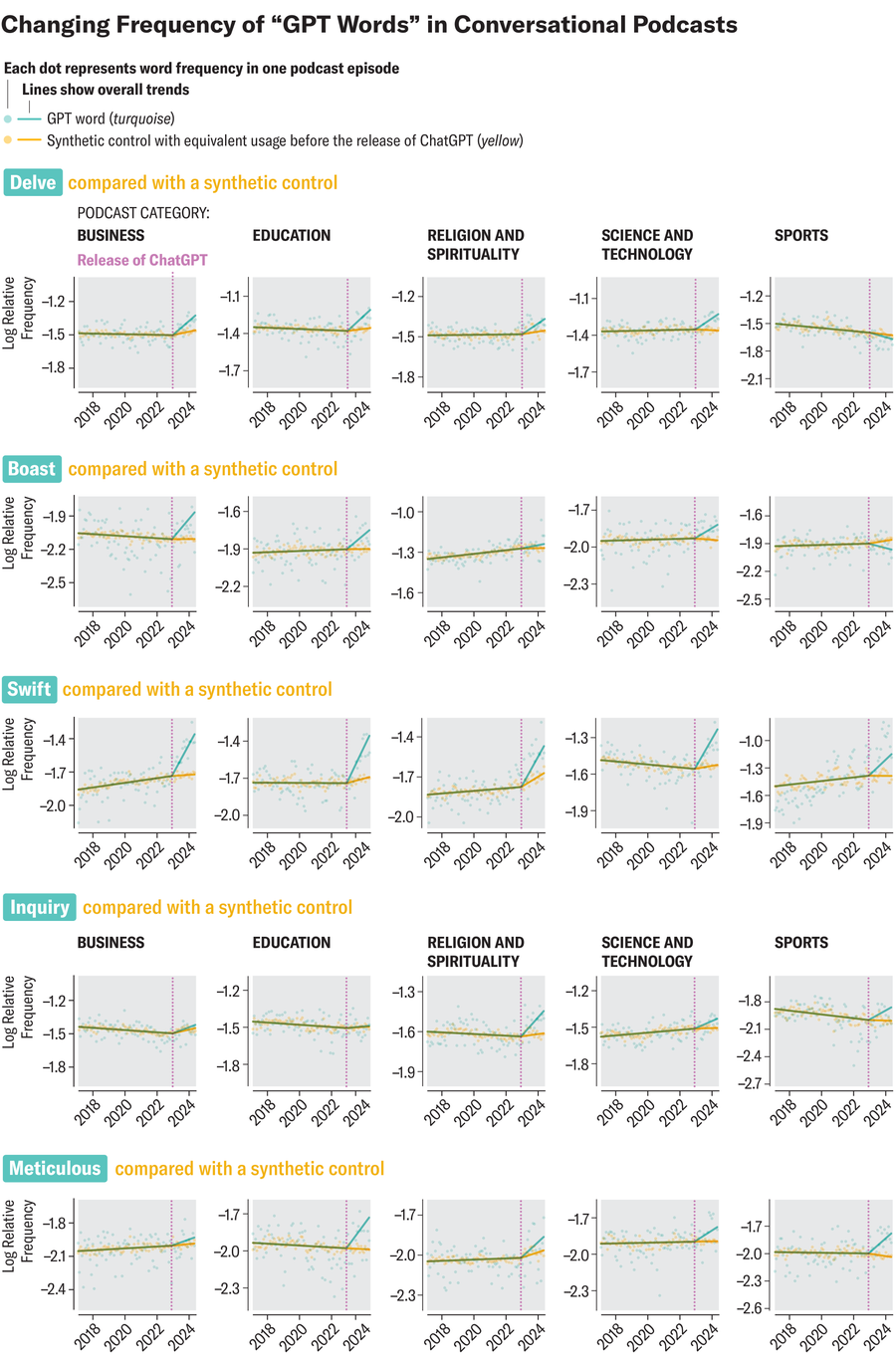

Words frequently used by ChatGPT, including “delve” and “meticulous,” are getting more common in spoken language, according to an analysis of more than 700,000 hours of videos and podcasts

After its release in late 2022, ChatGPT reached 100 million users in just two months, making it the fastest-growing consumer application in history. Since then the artificial intelligence (AI) tool has significantly affected how we learn, write, work and create. But new research shows that it’s also influencing us in ways we may not be aware of—such as changing how we speak.

Hiromu Yakura, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, first noticed differences in his own vocabulary about a year after ChatGPT came out. “I realized I was using ‘delve’ more,” he says. “I wanted to see if this was happening not only to me but to other people.” Researchers had previously found that use of large language models (LLMs), such as those that power ChatGPT, was changing vocabulary choices in written communication, and Yakura and his colleagues wanted to know whether spoken communication was being affected, too.

The researchers first used ChatGPT to edit millions of pages of e-mails, essays, and academic and news articles using typical prompts such as to “polish” the text or “improve its clarity.” Next, they extracted words that ChatGPT repeatedly added while editing, such as “delve,” “realm” and “meticulous,” dubbing these “GPT words.” The team then analyzed more than 360,000 YouTube videos and 771,000 podcast episodes from before and after ChatGPT’s release to track the use of GPT words over time. They compared the GPT words with “synthetic controls,” which were formed by mathematically weighting synonyms that weren’t frequently used by the chatbot—such synonyms for “delve,” for example, could include “examine” and “explore.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The team’s results, posted on the preprint server arXiv.org last week, show a surge in GPT words in the 18 months after ChatGPT’s release. The words didn’t just appear in formal, scripted videos or podcast episodes; they were peppered into spontaneous conversation, too.

“The patterns that are stored in AI technology seem to be transmitting back to the human mind,” says study co-author Levin Brinkmann, also at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development. In other words, a sort of cultural feedback loop is forming between humans and AI: we train AI on written text, it parrots a statistically remixed version of that text back to us, and we pick up on its patterns and unconsciously start to mimic them.

“AI is not a special technology in terms of influencing our behavior,” Yakura says. “But the speed and scale at which AI is being introduced is different.”

It may seem harmless—if a bit comical—for people to start talking like ChatGPT. But the trend carries deeper risks. “It’s natural for humans to imitate one another, but we don’t imitate everyone around us equally,” Brinkmann says. “We’re more likely to copy what someone else is doing if we perceive them as being knowledgeable or important.” As more people look to AI as a cultural authority, they may rely on and imitate it over other sources, narrowing diversity in language.

This makes it critical to track and study LLMs’ influence on culture, according to James Evans, a professor of sociology and data science at the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the study. “In this moment in the evolution of LLMs, looking at word distribution is the right methodology” to understand how the technology is affecting the way we communicate, he says. “As the models mature, these distributions are going to be harder to discriminate.” Scientists may need to look at broader linguistic trends beyond word choice, such as sentence structure and how ideas are presented.

Given that ChatGPT has changed how people talk just two and a half years into its adoption, the question becomes not whether AI is going to reshape our culture, but how profoundly it will do so.

“Word frequency can shape our discourse or arguments about situations,” Yakura says. “That carries the possibility of changing our culture.”