The last time you interacted with ChatGPT, did it feel like you were chatting with one person, or more like you were conversing with multiple individuals? Did the chatbot appear to have a consistent personality, or did it seem different each time you engaged with it?

A few weeks ago, while comparing language proficiency in essays written by ChatGPT with that in essays by human authors, I had an aha! moment. I realized that I was comparing a single voice—that of the large language model, or LLM, that powers ChatGPT—to a diverse range of voices from multiple writers. Linguists like me know that every person has a distinct way of expressing themselves, depending on their native language, age, gender, education and other factors. We call that individual speaking style an “idiolect.” It is similar in concept to, but much narrower than, a dialect, which is the variety of a language spoken by a community. My insight: one could analyze the language produced by ChatGPT to find out whether it expresses itself in an idiolect—a single, distinct way.

Idiolects are essential in forensic linguistics. This field examines language use in police interviews with suspects, attributes authorship of documents and text messages, traces the linguistic backgrounds of asylum seekers and detects plagiarism, among other activities. While we don’t (yet) need to put LLMs on the stand, a growing group of people, including teachers, worry about such models being used by students to the detriment of their education—for instance, by outsourcing writing assignments to ChatGPT. So I decided to check whether ChatGPT and its artificial intelligence cousins, such as Gemini and Copilot, indeed possess idiolects.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Elements of Style

To test whether a text has been generated by an LLM, we need to examine not only the content but also the form—the language used. Research shows that ChatGPT tends to favor standard grammar and academic expressions, shunning slang or colloquialisms. Compared with texts written by human authors, ChatGPT tends to overuse sophisticated verbs, such as “delve,” “align” and “underscore,” and adjectives, such as “noteworthy,” “versatile” and “commendable.” We might consider these words typical for the idiolect of ChatGPT. But does ChatGPT express ideas differently than other LLM-powered tools when discussing the same topic? Let’s delve into that.

Online repositories are full of amazing datasets that can be used for research. One is a dataset compiled by computer scientist Muhammad Naveed, which contains hundreds of short texts on diabetes written by ChatGPT and Gemini. The texts are of virtually the same size, and, according to their creator’s description, they can be used “to compare and analyze the performance of both AI models in generating informative and coherent content on a medical topic.” The similarities in topic and size make them ideal for determining whether the outputs appear to come from two distinct “authors” or from a single “individual.”

One popular way of attributing authorship uses the Delta method, introduced in 2001 by John Burrows, a pioneer of computational stylistics. The formula compares frequencies of words commonly used in the texts: words that function to express relationships with other words—a category that includes “and,” “it,” “of,” “the,” “that” and “for”—and content words such as “glucose” or “sugar.” In this way, the Delta method captures features that vary according to their authors’ idiolects. In particular, it outputs numbers that measure the linguistic “distances” between the text being investigated and reference texts by preselected authors. The smaller the distance, which typically is slightly below or above 1, the higher the likelihood that the author is the same.

I found that a random sample of 10 percent of texts on diabetes generated by ChatGPT has a distance of 0.92 to the entire ChatGPT diabetes dataset and a distance of 1.49 to the entire Gemini dataset. Similarly, a random 10 percent sample of Gemini texts has a distance of 0.84 to Gemini and of 1.45 to ChatGPT. In both cases, the authorship turns out to be quite clear, indicating that the two tools’ models have distinct writing styles.

You Say Sugar, I Say Glucose

To better understand these styles, let’s imagine that we are looking at the diabetes texts and selecting words in groups of three. Such combinations are called “trigrams.” By seeing which trigrams are used most often, we can get a sense of someone’s unique way of putting the words together. I extracted the 20 most frequent trigrams for both ChatGPT and Gemini and compared them.

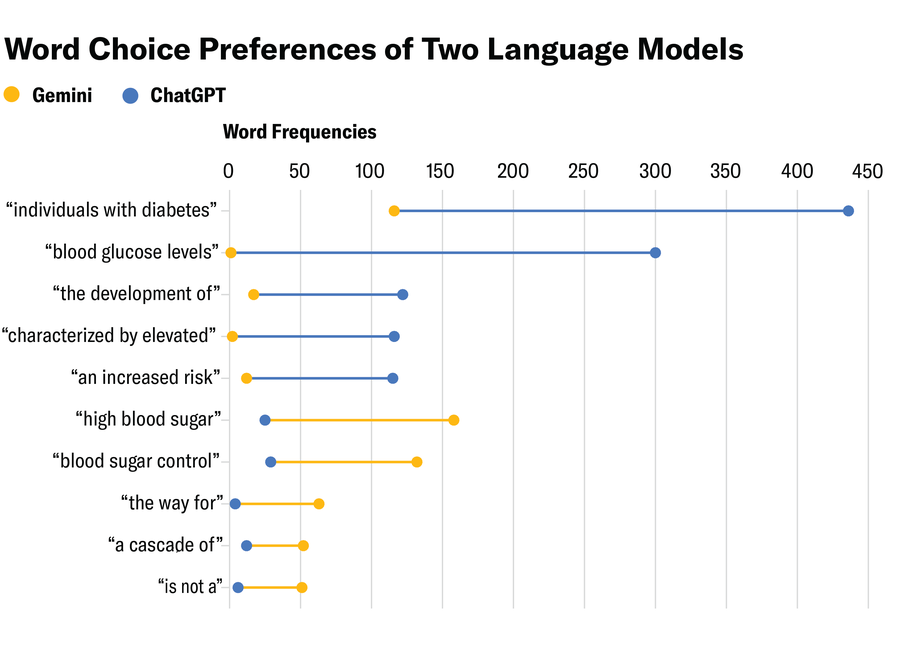

ChatGPT’s trigrams in these texts suggest a more formal, clinical and academic idiolect, with phrases such as “individuals with diabetes,” “blood glucose levels,” “the development of,” “characterized by elevated” and “an increased risk.” In contrast, Gemini’s trigrams are more conversational and explanatory, with phrases such as “the way for,” “the cascade of,” “is not a,” “high blood sugar” and “blood sugar control.” Choosing words such as “sugar” instead of “glucose” indicates a preference for simple, accessible language.

The chart below contains the most striking frequency-related differences between the trigrams. Gemini uses the formal phrase “blood glucose levels” only once in the whole dataset—so it knows the phrase but seems to avoid it. Conversely, “high blood sugar” appears only 25 times in ChatGPT’s responses compared to 158 times in Gemini’s. In fact, ChatGPT uses the word “glucose” more than twice as many times as it uses “sugar,” while Gemini does just the opposite, writing “sugar” more than twice as often as “glucose.”

Eve Lu; Source: Karolina Rudnicka (data)

Why would LLMs develop idiolects? The phenomenon could be associated with the principle of least effort—the tendency to choose the least demanding way to accomplish a given task. Once a word or phrase becomes part of their linguistic repertoire during training, the models might continue using it and combine it with similar expressions, much like people have favorite words or phrases they use with above-average frequency in their speech or writing. Or it might be a form of priming—something that happens to humans when we hear a word and then are more likely to use it ourselves. Perhaps each model is in some way priming itself with words it uses repeatedly. Idiolects in LLMs might also reflect what are known as emergent abilities—skills the models were not explicitly trained to perform but that they nonetheless demonstrate.

The fact that LLM-based tools produce different idiolects—which might change and develop across updates or new versions—matters for the ongoing debate regarding how far AI is from achieving human-level intelligence. It makes a difference if chatbots’ models don’t just average or mirror their training data but develop distinctive lexical, grammatical or syntactic habits in the process, much like humans are shaped by our experiences. Meanwhile, knowing that LLMs write in idiolects could help determine if an essay or an article was produced by a model or by a particular individual—just as you might recognize a friend’s message in a group chat by their signature style.