A single, freely available, noninvasive brain scan done in just a few minutes during midlife can predict what chronic diseases are most likely to appear in the future, empowering people to make diet and lifestyle changes that mitigate their risk even decades before symptoms begin to show. Getting the jump on degenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease could have a huge impact on health outcomes later in life.

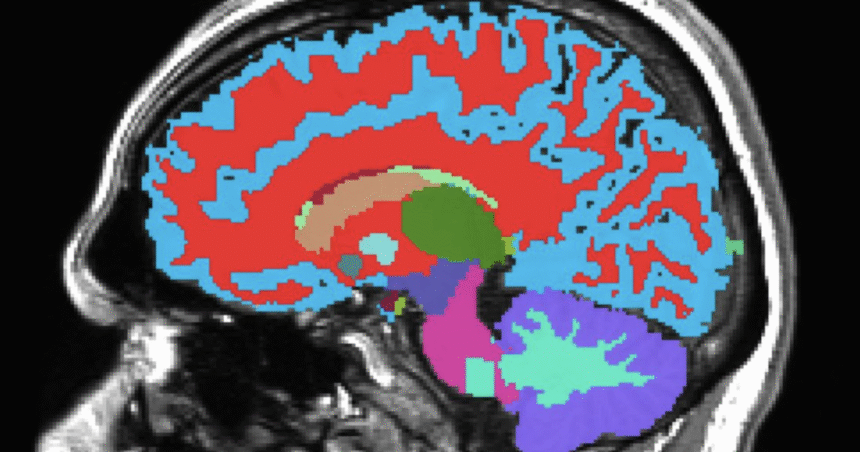

Scientists at Duke and Harvard Universities and the University of Otago have developed the Dunedin Pace of Aging Calculated from NeuroImaging (DunedinPACNI) scan, which as the name suggests, scans the brain to determine how fast it is aging. It didn’t just predict cognitive impairment, accelerated brain atrophy and conversion to diagnosed dementia, it could also provide a risk factor for physical frailty, poor health, other future chronic diseases and mortality.

Early Alzheimer’s Detection | Check This Out!

“The way we age as we get older is quite distinct from how many times we’ve traveled around the sun,” said Ahmad Hariri, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke. “What‘s really cool about this is that we‘ve captured how fast people are aging using data collected in midlife. And it’s helping us predict diagnosis of dementia among people who are much older.”

Training the tool on 860 New Zealanders born between 1972 and 1973, who have been studied since birth, DunedinPACNI is based on scans of their brains taken at age 45. Through this foundation, covering around 20 years of brain health and other metrics such as blood pressure and organ function, the system can estimate a score for how quickly each person is aging.

The researchers then expanded the population to include large datasets from the UK, the US, Canada and Latin America.

While the concept is not a new one – AI has rapidly accelerated the development of predictive diagnostics – the DunedinPACNI tool differs in that its base learning is on the same individuals as they grew older, not a population of different people who had received scans. Because seeing how one person’s brain looks at, for example, age 35, and another person’s brain at age 60, those methods become more age-based across a population than a longitudinal measure of each individual.

“Things that look like faster aging may simply be because of differences in exposure,” said Hariri, referring to factors like lead in gas and cigarette smoke.

A constant seen across all datasets was that a faster aging score when it came to brain function was closely tied to poorer performances on cognitive tests and greater shrinkage in the memory region of the hippocampus. These people were also much more likely to have pronounced cognitive decline in the future.

When the team used their tool to assess Alzheimer’s disease risk, using 624 brain scans from individuals aged 52 to 89, the people who were highlighted as the fastest aging when they started the study were 60% more likely to develop dementia.

“Our jaws just dropped to the floor,” Hariri said of seeing these results.

DunedinPACNI results weren’t just confined to brain health, with faster aging increasing the likelihood of higher frailty and age-related conditions like heart attack, lung disease and stroke. In fact, those who were aging fastest in midlife were 18% more likely to develop a chronic disease within just years, compared to individuals who had average aging scores. These fast agers were also 40% more likely to die within this window of time.

“The link between aging of the brain and body are pretty compelling,” Hariri said.

And another sobering statistic that the DunedinPACNI age score revealed: Aging speed and dementia was strongly associated regardless of background and socioeconomic status.

“It seems to be capturing something that is reflected in all brains,” Hariri added.

While some people might prefer to stick to reading tea leaves than seeing their aging score through this system, it’s not built to deliver a death sentence but to buy an individual crucial time to make changes that can have a big impact on their future health. Despite the incredible effort going into treating dementia, treatment becomes less effective the further along the disease is.

“Drugs can’t resurrect a dying brain,” Hariri said.

Given that gloomy forecast, general consensus is that treating the condition as early as possible is extremely important in shielding neurons from damage and protecting brain health.

The researchers also plan to look at other factors – mental health conditions, poor sleep – through the DunedinPACNI lens, to see how individuals may age differently. While more work is needed to turn the tool into an everyday clinical assessment, it’s expected to first be used by medical researchers assessing aging via MRI data, to uncover specific aging biomarkers that can’t be identified through other tests like blood samples.

“Because we live longer lives, more people are unfortunately going to experience chronic age-related diseases, including dementia,” Hariri said. “We really think of it as hopefully being a key new tool in forecasting and predicting risk for diseases, especially Alzheimer’s and related dementias, and also perhaps gaining a better foothold on progression of disease.”

The results were published July 1 in the journal Nature Aging.

Source: Duke University