ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

This article was adapted from David Epstein’s Substack newsletter, “Range Widely,” and references the story “The DIY Scientist, the Olympian, and the Mutated Gene” that he wrote for ProPublica in 2016. That story also became an episode of “This American Life.”

Jill Dopf Viles — self-taught genetic detective, the central figure in the most interesting story I’ve ever reported and my friend — passed away last month in Gowrie, Iowa, at 50.

I’m heartbroken that Jill did not live to see the publication of her book — “Manufacturing My Miracle: One Woman’s Quest to Create Her Personalized Gene Therapy — which came out last week. I know how much she treasured the fact that she would soon be able to call herself “author.”

Here is a paragraph from her book:

“Every gain I’d made in learning more about my genetic disease had involved some type of deception — to do my family’s underground blood draw in 1996 required that phlebotomy supplies be lifted from a hospital and a nurse secretly visit our home; gaining journalist David Epstein’s interest began with a wild exaggeration in my email subject line: ‘Woman with muscular dystrophy, Olympic Medalist—same mutation’; and I’d adopted the lexicon of a research scientist to gain a client rate for Priscilla’s genetic testing (the cost for clients was half what was charged to individual patients).”

If I was deceived, I’m grateful for it. In that paragraph, Jill is describing just a bit of the effort that went into figuring out that she had a rare form of muscular dystrophy called Emery-Dreifuss, which causes muscle wasting, and also an even rarer form of partial lipodystrophy, which causes fat to vanish from certain parts of the body. Jill had been told for years that she didn’t have either of these, never mind both.

After my first book, “The Sports Gene,” came out in 2013, I was on “Good Morning America” talking about genetics, and Jill happened to be within earshot of her TV. “I thought, oh, this is divine providence,” Jill later told me. So she sent me that email with the provocative subject line. She followed up by sending me a batch of family photos and a bound packet outlining her theory: that she and Canadian sprinter Priscilla Lopes-Schliep — bronze medalist in the 100-meter hurdles at the 2008 Olympics — shared a genetic mutation.

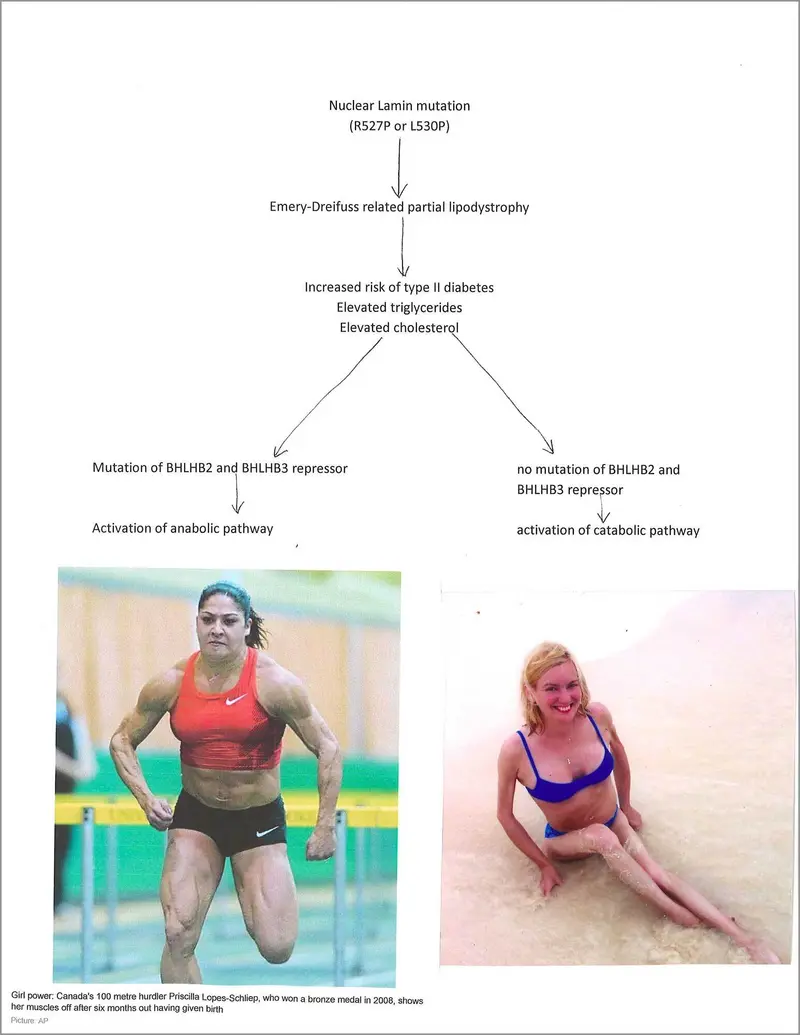

On the face of it, this seemed ridiculous. One could hardly find a picture of two more different women. Take a look at this page from the packet Jill sent me:

The packet outlined in granular detail why Jill thought, just from looking at pictures of Priscilla, that the two women shared a genetic mutation that caused the same fat wasting, but because Priscilla didn’t also have muscle wasting — quite the contrary — her body had found some way to “go around” muscular dystrophy.

If Jill was right, she thought, perhaps scientists could study both of them and figure out how to help people with muscles like Jill’s develop muscles a little closer to Priscilla’s end of the human physique spectrum. Jill was sharing all this with me because she wasn’t sure how best to contact Priscilla and hoped I would facilitate an introduction.

Jill’s hypothesis struck me as unlikely, to say the least. But her presentation in the packet was so interesting, and her knowledge of the underlying genetics and physiology so thorough, that I felt her idea deserved a hearing. I reached out to Priscilla; she agreed to meet Jill, and after comparing body parts in a hotel lobby, Jill convinced her to get a genetic test. Long story short, Jill turned out to be right. She and Priscilla had a mutation in the same gene, albeit at neighboring locations.

The discovery led Priscilla to get urgent care for a serious health condition that had previously been overlooked because of her obvious fitness. Jill and I shared this story in an episode of “This American Life” in 2016 — which was rerun last week in her honor.

After that story ran, Jill’s genome became the subject of research, exactly as she’d hoped. Today, in a lab in Iowa, there are fruit flies known as “Jill” flies, because they have been engineered to carry her same mutation. As expected, Jill flies have severely limited mobility. But just recently, a scientist conducted a genetic experiment in which she increased the production of a particular protein in the Jill flies. Suddenly, they began to move like normal fruit flies.

The breadth of life contained in Jill’s new book is incredible.

She was a child the first time she heard a doctor discussing her own death with her mother. The indignities of adolescence and young adulthood that she endured were legion, starting with spontaneous falls in school, followed by kids looping their fingers around her arms and legs and asking if her mother fed her.

Jill’s condition accelerated with puberty, so the bodily changes that are confusing for any teenager were absolutely harrowing for her. Almost overnight she lost the ability to do things she loved, like skate or ride a bike.

At one point in her early teen years, a doctor ordered pictures of Jill’s posture, which forced her into a strange and humiliating photo session that hadn’t been properly explained beforehand:

“I had seen these photos before — a stark, frozen moment of a patient’s greatest vulnerability, the body positioned in a way nature and the photographer dictate, all except for the eyes. The eyes cannot be manipulated or coaxed. It is often said that the eyes are the windows to the soul. Maybe that is why black bars are printed over the eyes of the patient. Perhaps this is done to protect the patient’s anonymity, but I wonder if it isn’t really done to shield the peering eyes of the medical community from the humanity before them.”

In college, when Jill rushed a sorority, she couldn’t keep up with fellow pledges as they walked across campus. When a man who had been following the group saw Jill lag behind, he crept up and exposed himself to her. “I had been targeted because I was weak,” Jill writes. “I had assumed the plight of the injured gazelle, the one separated from the herd with a lame leg. … Any normal eighteen-year-old would bolt for safety, but I remained glued in place, the shame of my predicament filling every cell of my being. I was trapped alongside a simple street curb, something I couldn’t climb, no matter my desperate need to get away.”

But even more powerful in “Manufacturing My Miracle” than the candid humiliations are the scenes of family, love and hope.

Jill’s wry humor comes through when she writes about dating. At one point she used a Match.com profile to come up with the estimate that at least 1% of men are open to dating a woman with a disability. In typical Jill fashion, rather than lamenting the other 99%, she was thrilled that this meant that if she got her profile in front of enough men, she could have a new date every week of the year.

Jill eventually met Jeremy, the man she would marry. She writes about aspects of their relationship with such tenderness that I frequently paused after a passage just to sit and think about her words for a few moments. “I recalled our first weeks of dating when Jeremy made a heartfelt observation,” Jill writes. “Previously, as a single man, he often went an entire weekend without saying even one word aloud. It was such a contrast to the way I lived my life. I was known to strike up a conversation with the caller of a misdialed number, banter with strangers in a bookstore, or chat freely with the checkout clerk at the grocery store.”

In their second month of dating, Jill and Jeremy attended the gigantic Iowa State Fair. Here’s how Jill remembered it:

“I lived ten years in a single night, clutching carnival booty tightly to my chest as Jeremy walked up and down the rows of carnival games, taking entirely too long to decide which to go for. ‘What’s taking you so long?’ I asked.

‘I’m trying to find one you can play,’ he said.

My eyes filled with tears.”

After our “This American Life” segment came out in 2016, Jill became a bit of a celebrity among people struggling to figure out their own mysterious illnesses.

She developed into a sort of clearinghouse for people with undiagnosed muscle conditions seeking help. She kept in constant touch with a man in rural Pakistan who sent her a video of his struggle to rise from his knees following daily prayers at a local mosque. She navigated immense cultural and logistical barriers to help him get a genetic test. “She was a worldwide person,” her mother, Mary, told me recently, “just out of her little office in Gowrie, Iowa.”

Jill became so fluent in genetics that she was perceived as a scientist when she called labs, lab supply companies or pharmaceutical companies. Toward the end of her life, that fluency allowed her to obtain an experimental gene therapy that isn’t actually available for nonresearch purposes. She knew the drug was both promising and potentially deadly, and with a loving husband and college student son in mind, she was hesitant. “I no longer had a fear of death,” Jill writes in her book, “but this did not imply that I wanted to die. My wish was the opposite, but without a life partner and a child, I wouldn’t need to consider anyone’s viewpoint but my own.”

As always, she did consider others, and at the time of her death she had not gone through with this final experiment.

In April, Jill and Jeremy drove to Chicago to attend a wedding. Mary shared photos with me, and it’s the same Jill I began talking to in 2013: dressed impeccably, every strand of blond hair in its right place. She took great care and pride in her appearance. Looking at the pictures, it is extremely hard to imagine that Jill was less than two months away from dying.

Her brother Aaron, afflicted with the same condition, had passed away in 2019. Four of the five siblings inherited the mutation, though the disease severity differed — likely moderated by other parts of the genome. In “Manufacturing My Miracle,” Jill writes of the difficult decision regarding whether or not to have a child, given the 50-50 chance of passing down her mutation. Her son, Martin, did not inherit the mutation.

Shortly before the “This American Life” episode ran, Jill got nervous and wondered if we should hit pause on it. She worried that listeners would only focus on her decision to have a child and criticize her for being selfish. We talked for hours about the potential outcomes. Jill and I had been in touch for three years by that time, and we were going to stick together as friends no matter what criticism came. She decided we should forge ahead. Fortunately, the response was the most overwhelmingly positive of any story I’ve ever been involved with.

Jill and I met up in Chicago after that so I could watch her give an invited lecture. We kept in touch over the years. Sometimes we went months without talking before a burst of calls back and forth.

By this spring, it had been an unusually long while since we last talked. We emailed, but no phone calls. Mary told me that Jill had recently bought a new dress that she planned to wear when giving talks about her book. At a visitation before the funeral, she’ll be wearing her book dress.

Mary added that, a few weeks before Jill passed, she caught pneumonia and never recovered. Mary told me her voice was weak. “I kept telling her to call you,” Mary said. “But she kept saying: ‘I want my voice to be stronger. I want my voice to be stronger before I call David.’”

I’m crestfallen that I didn’t hear from her again, but I think her voice was plenty strong.